In public policy, too often it’s the loudest voice in the room that makes the decision, says Brandon Welsh, professor of criminology and criminal justice and co-director of the Crime Prevention Lab at Northeastern University.

“We aren’t living in an evidence-based society,” he says.

This is especially true when it comes to crime and justice policy, he says, “where opinions matter more than facts” and policymakers espouse programs almost like “favorites of the month,” he continues.

Welsh cites the Drug Abuse Resistance Education (D.A.R.E.) program of the 1980s and 1990s, which began with the “best of intentions,” he says, but which studies later proved to be “an abject failure,” doing little more than familiarizing grade-schoolers with illegal drug paraphernalia.

“It introduced a whole generation of kids to drugs,” Welsh says.

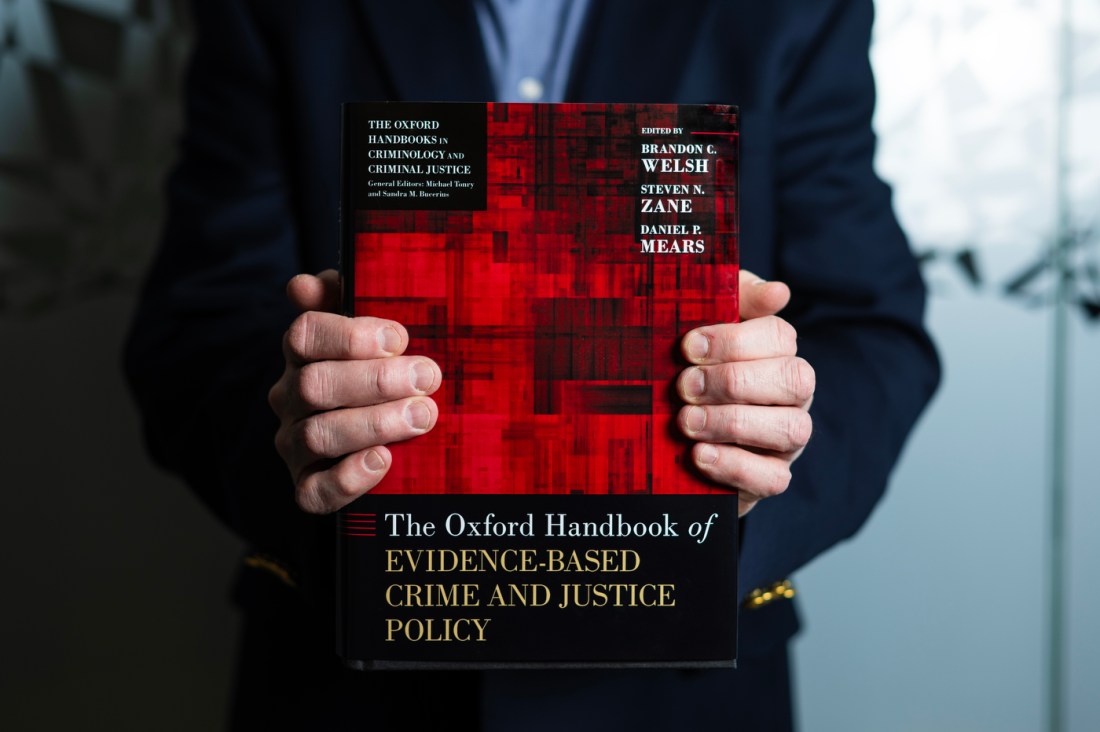

“The Oxford Handbook of Evidence-Based Crime and Justice Policy,” which Welsh co-edited with Daniel Mears and Steven Zane, both of Florida State University, gathers scholars of law, criminology and public policy in a volume focused on changing this flavor-of-the-month mindset, espousing criminal justice and public policy built on evidence-based research.

What amounts to nearly a “three-year international research project,” Welsh says, the editors aimed “to bring together the sharpest minds [and] the biggest critics [within] evidence-based policy, in all its dimensions.”

Welsh, Mears and Zane began by reaching out to “a wide range of scholars,” Welsh says. “We wanted representation across the board, including people of color, people working in different parts of the world, working in different areas, different topics. We wanted scholars and practitioners, people who were engaged in the research.”

From this “dream team,” as Welsh calls them, the editors solicited articles based on the authors’ interests and what the editors considered the most pressing questions in the field. “These were original works, original pieces of scholarship,” Welsh points out.

In addition to “showcasing the gains that have been made in the last 25 years,” Welsh says, “we were going to showcase what’s working, what’s not working, the challenges and also … what’s going on in the criminal justice system, the juvenile justice system. Alternative approaches.”

Welsh points to Washington state as one of the best examples of the evidence-based approach’s success. “Their emphasis [and] investment in research,” Welsh says, has led to a dramatic “reduction in victimization [and] reduction in crime rates.”

The plans for two new prisons were forestalled thanks to these improvements in the system, Welsh says. “There is a third one that is still in the forecast that they may need by 2030 — but now that one’s on thin ice.”

So, Welsh’s new “Oxford Handbook” includes a chapter on what can be learned from the Washington state model.

Welsh most hopes that the book will “promote a greater use of evidence-based policy, from the need for greater social equity — [as in] the need to address racial disparities in sentencing — to a host of critical issues that our field is confronting.”

Zane received his Ph.D. from Northeastern — Welsh was his doctoral adviser — and the book contains several other Northeastern-affiliated authors: professors of criminology and criminal justice Natasha Frost, Eric Piza and Daniel T. O’Brien and doctoral student Heather Paterson.

For Welsh, the principal question of any policy or program should be, “Are there efforts to lead to social impact?”

With any hypothetical policy or program, “We have to develop it, test it and scale it up. And [assume] it’s still working, it’s meeting its objectives.” Then, Welsh says, the question policymakers have to ask is, “Is it leading to sustainable, meaningful change?”

“Are we — and this is the really difficult thing — are we beginning to chip away at the resistance to change?”