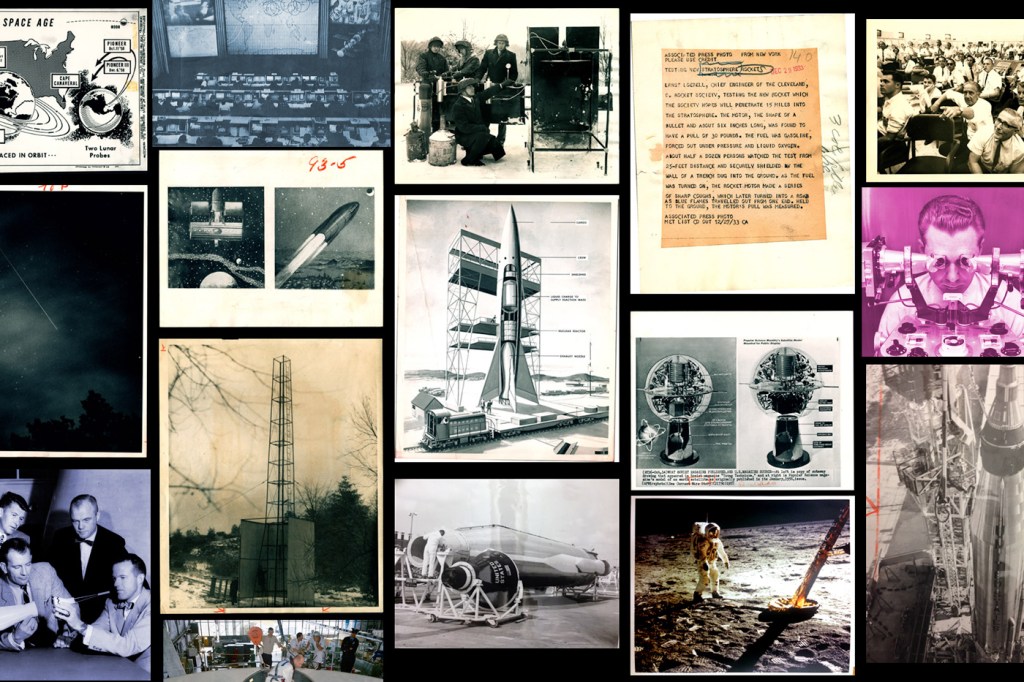

The space age takes flight

In 1865, Jules Verne published From Earth to the Moon, a novel in which characters attempt to build a cannon large enough to lob three people up to our nearest celestial neighbor.

In 1865, Jules Verne published From Earth to the Moon, a novel in which characters attempt to build a cannon large enough to lob three people up to our nearest celestial neighbor.

It was 1961 and the United States was in the uncomfortable position of playing catch-up with the Soviet Union.

On July 20, 1969, just after 8:15 p.m. on the East Coast, the American lunar module “Eagle” landed on the surface of the moon. Six hours later, Neil Armstrong was the first human being to set foot on a celestial body other than Earth.

NASA had a lot of questions to answer before it could send astronauts to the moon. Were there harmful effects from being in space for too long? Could astronauts work outside their capsule? How would two spacecraft detach from each other and later reconnect in flight?

Northeastern students and faculty reflect on the role of humanoid robots in deep space exploration, sending humans to Mars, and the need for reusable spacecrafts.

Space exploration “has always been about international cooperation and the betterment of humanity,” says Mai’a Cross, a professor at Northeastern whose newest research focuses on the international collaboration that fostered the Space Race of the 1960s. But some politicians and military officials describe space missions as necessary in order to “prepare for war in space,” she says.

Laptops or barcodes? Sneaker insoles or lava lamps? Wireless headphones or GPS? See if you can do better than we did.

A drill to extract frozen water from beneath the planet’s surface. A rover to accompany astronauts as they work. The Northeastern students who designed and built this technology recently showcased their work at Boston’s Museum of Science.