Is Elon Musk’s $1 million giveaway for swing state voters illegal? Legal expert says it “really puts our system to the test”

The Tesla CEO giving away $1 million to registered voters in swing states raises serious questions about the blurry legality around campaign financing, Northeastern’s Jeremy Paul says.

Elon Musk has once again made headlines, this time for his latest attempt to influence the 2024 presidential election.

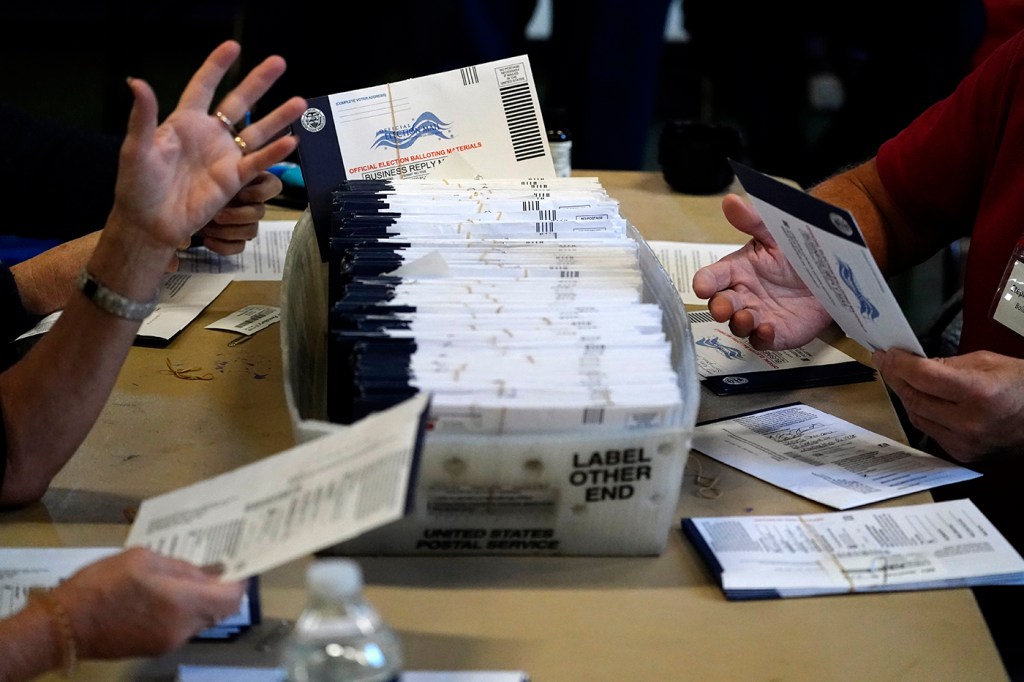

The tech billionaire announced that every day leading up to Election Day on Nov. 5, he will give away $1 million to a registered voter in swing states as long as they sign a petition put out by his super PAC.

Two winners have already been announced, and the giveaway has already attracted national attention, with many questioning the legality of Musk’s strategy.

The lottery is only Musk’s most recent eye-catching move to support Donald Trump’s presidential campaign. Through his America PAC, the billionaire has already given $75 million to the Republican presidential nominee’s bid to return to the White House.

So, is Musk’s $1 million giveaway illegal? Jeremy Paul, a professor at Northeastern University School of Law, says the answer is murky, but “it really puts our system to the test.”

“What Musk is doing is he’s trying to take the system as it is and manipulate it,” Paul says. “He’s not actually paying anyone to vote. He’s paying people to sign this petition that he’s gathering in support of the First and Second Amendment.”

The goal of the giveaway is to “get 1 million registered voters in swing states to sign in support of the Constitution, especially freedom of speech and the right to bear arms,” Musk shared on X. However, the program is only available to a certain group of people: registered voters in swing states like Pennsylvania, Georgia, Nevada, Arizona, Michigan, North Carolina and Wisconsin.

“The signature thing that he is ostensibly paying for is pretty obviously a dodge around the fact that he’s not allowed to pay people to vote,” Paul says. “The second dodge is that in order to sign this petition and be eligible for this money, you have to be registered to vote. That makes it seem like he’s actually paying people to register.”

From that perspective, Paul says there is an argument that it’s illegal and “almost certain” to bring legal challenges. Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro already called the lottery “deeply concerning” in an interview with NBC’s “Meet the Press” and called on law enforcement to investigate.

The problem, Paul says, is that even though the program is clearly “targeted and designed to get around what’s supposed to be the law,” it would likely be a difficult case to make in court.

“Of course [Musk will] say, ‘I’m not paying anyone to vote. I’m only paying them to sign the petition,’” Paul says. “If this were a formal petition and it were to get a petition initiative on the ballot or to be in support of a candidate whose gathering signatures, that would firmly be illegal.”

While U.S. law aims to create a firm boundary between politics and money, Musk’s giveaway and broader election efforts highlight one area that has remained blurry: campaign finance.

Direct contributions to a political candidate’s campaign are limited by law. But super PACs, tax-exempt entities that pool donations and work to independently support a candidate, have historically been a work-around.

More relevant to Musk’s swing state giveaway are the small ways both political parties have historically tried to bring in voters, like offering child care services or a ride to the polls, Paul says. Methods like these are “deeply part of our longstanding political process,” which raises the question, “Where is the line?” In Musk’s case, it’s fairly obvious, Paul says.

“If I drive you to the polls, am I paying you to vote? The answer to that is clearly not, but that’s why this is a hard line to close,” Paul says. “In all of law there’s what you would consider a de minimis requirement. It’s such a trivial thing –– who cares? But if you start offering $1 million, it’s not trivial anymore.”

“Whatever it is, it’s a reprehensible practice,” Paul adds. “It really shows the mentality of Elon Musk who thinks that because he’s super wealthy he gets to decide who the president is. … This is a loophole that we’ll hopefully figure out a way to close in the future because it’s anti-democratic trend.”