Wireless gear shifting systems on bikes can be hacked. Northeastern cybersecurity experts identify the problem and offer solutions

Cyclists go through a checklist before rolling out for a ride: water bottles, tire pressure, road route.

The last thing they think about is the possibility of their bikes being hacked, especially while they are in the middle of a ride. But that may become a bigger concern as these modes of transportation are outfitted with more high-tech components, new Northeastern research shows.

Aanjhan Ranganathan, a Northeastern professor in the Khoury College of Computer Sciences, is one of several cybersecurity scientists who has published new findings that detail security vulnerabilities in wireless gear shift systems featured in high-end bicycles used by professional and amateur cyclists.

Ranganathan was one of the two Northeastern researchers working on the project. Alongside him was Maryam Motallebighomi, a doctoral student in Northeastern’s Khoury College whose research focus is on wireless security.

Wireless gear shifting systems are still relatively new to the cycling world — the first wireless systems debuted in 2015 — but they have been praised for their advantages over mechanical and wired electric gear shifting systems, offering greater precision, control and ease of use, proponents have said.

The electronic wireless systems transmit over-the-air signals between a bike’s shifter and its derailleurs. However, these systems are ripe for potential attack since those signals are easily interceptable, researchers have found, allowing hackers to program bikes to shift into gears without being prompted by the rider and even be jammed completely.

.

The researchers did not conduct their work in a vacuum; they have been working in collaboration with Shimano, one of the companies making wireless gear shifting systems, to fix the vulnerabilities. The company is now in the process of deploying a software update that helps address the security concerns Ranganathan and his colleagues discovered, he says.

“They have been extremely responsive,” Ranganathan says, adding that when the CEO of Shimano was presented with the researchers’ findings he wanted to issue a fix “as soon as possible.”

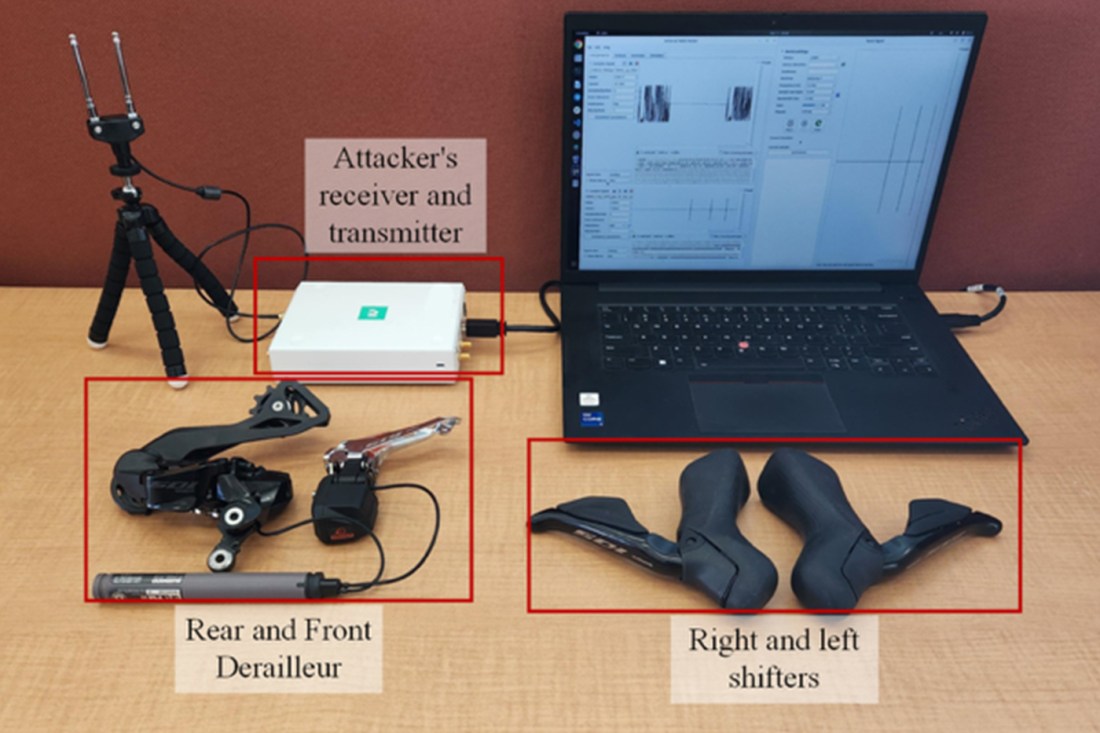

For the project, the team purchased several wireless gear shifting systems from Shimano and installed them on their own bikes. Using an off-the-shelf radio receiver capable of recording and transmitting signals, the researchers were easily able to intercept the bikes’ communication system.

“One of the attacks we found was replay attacks,” Ranganathan says. “Let’s say I’m close to someone who is practicing. I’m able to record the signals like upshift and downshift gear signals. I can actually replay those signals back at any point in the future to cause those gears to shift.”

These attacks can be executed with pinpoint accuracy and as far as 10 meters (32 feet) away from a bike in motion, according to the researchers.

“Even if you put 100 bikes close to each other in a race, I can actually pick and choose which bikes stop working,” he says.

Ranganathan says these kind of vulnerabilities can easily be exploited by those looking to gain an unfair advantage in competitive races. Without much trouble, someone could cause a rider’s bike to malfunction in the middle of a ride, he adds.

Cheating is not unheard of in cycling, he says, noting that cyclists have been fined, suspended or banned for taking performance-enhancing drugs and for other tactics.

At this year’s Olympics Games, cycling officials used scanners and X-ray imaging devices to combat “motor doping,” a term used to describe riders who place hidden electric motors in their bikes to help them win races, for example.

“The competitive sport’s environment is becoming adversarial,” he says.

There are a number of measures that can be implemented to make these systems much more secure, which the team has presented to Shimano, Ranganathan says.

One of the biggest security issues the team found was that hackers could cause bikes to change gears based on signal recordings they collected days beforehand.

To address this, wireless gear shift makers can implement a “rolling code” system, he says. This would work by having the gear shifting system change the transmission signal it sends out every minute or so, making any recording captured hours, days or months beforehand invalid.

“That’s the fundamental, basic way they can fix it,” he says, adding that it isn’t a perfect solution since it will require both the bike’s shifter and derailleurs to be in perfect sync, which can be complex to achieve.

Another solution would be to monitor and ensure that any signal that activates the gear shifting system needs to be within very close distance to the bike.

“If you can actually continuously keep measuring the distance from where the signals are coming from, that’s an easy fix,” he says. “That way you are forcing the attacker to be really close to you.”

The team presented their findings this week at the 18th USENIX WOOT conference in Philadelphia.