Published on

In between teaching and practicing, this Northeastern professor finds time to coach a Boston sled hockey team

Physical therapy professor Luke Brisbin helps out the players on Boston I.C.E. Storm’s adaptive ice hockey team, founded and managed by athletes with physical disabilities.

It’s easy to get behind a good hockey team. Just ask any Husky who’s been to the men’s or women’s Beanpot tournaments.

This is partially why Northeastern University professor Luke Brisbin spends his free time working with Boston I.C.E. Storm’s sled hockey teams.

Sled hockey is an adaptive form of ice hockey. In sled hockey, players are seated in a sled with a blade at the bottom and glide across the ice using a pick. They also navigate the puck using a modified hockey stick.

Despite the difference in equipment, sled hockey promises all the intensity of standup hockey, down to the raucous nature.

When I.C.E. Storm players find themselves on the receiving end of a body check, Brisbin awaits them on the benches. When the assistant clinical professor of physical therapy at Northeastern isn’t teaching or working, he’s volunteering with this adaptive hockey team for players with physical disabilities.

“As a physical therapist (I want) to promote physical activity and especially promote physical activity for people who may have barriers to it,” Brisbin said. “Any time that I could support an organization that’s trying to provide those opportunities for people, I definitely want to be a part of it.”

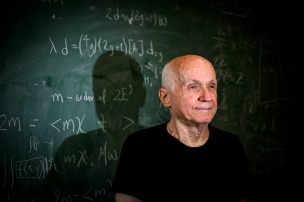

Brisbin earned his doctorate from Northeastern

Brisbin started out as a student at Northeastern, earning his doctorate in physical therapy through a six-year program. He graduated in 2016 and became an adjunct professor in 2017 between working at an outpatient orthopedics clinic. In 2022, Brisbin began teaching as a full-time assistant clinical professor in Northeastern’s physical therapy program while working at a clinic run by Boston Medical Center.

Brisbin started out volunteering at I.C.E. Storm practices in 2021, answering questions for players, giving them advice on any pain they might have, suggesting stretches and exercises to do, and helping them adjust their sleds so they can move the best they can. Then, in 2023, he was asked to join the board of directors.

“As I started working with them and getting to know people, just seeing how supportive everyone was in the community they built, it definitely became something that I wanted to become more a part of,” he said. “When they asked me if I’d like to be a member of the board, it just allowed me to be involved in some of the other decision making with the organization and try to make some decisions on how the team moves forward and grows.”

Aside from drawing on his professional background, Brisbin also draws on his upbringing in Colorado Springs, Colorado, where he played ice and roller hockey in high school before going on to play club roller hockey at Northeastern. He also dabbled in sled hockey.

“I grew up as a fan,” Brisbin said. “I (also had) a very close friend and neighbor who has autism and he was a big hockey fan as well. We would play street hockey and then we found a sled hockey league in our town. He decided he wanted to give that a try and he needed someone to push the sled, so I was his pusher. That gave me some exposure to it … and when this other opportunity came up, I knew it would be a fun opportunity.”

I.C.E. stands for include, compete, and empower

Boston I.C.E. Storm was founded in 2018 as a way for athletes with physical disabilities to play hockey. I.C.E. stands for include, compete, and empower. The sled hockey team is part of the Northeast Sled Hockey League and consists of players of different ages and abilities from across the area.

“It’s geared more towards physical disabilities, but with that being said, we won’t turn anyone aways,” said Jennifer Ford, president of the board of directors of I.C.E. Storm. “For many of the players, it’s much bigger than just a sport. It’s about community. Many of our athletes, their baseline is living in a world that doesn’t consider their needs on many levels so it’s very empowering when they’re in a space where they’re not the minority, where accessibility matters.”

While the organization’s focus now is their sled hockey team, Brisbin said the goal is to eventually expand and develop other sports teams for players with disabilities, like wheelchair basketball and wheelchair lacrosse.

“(It’s a) really creative community and brings people together around sports that may have difficulty accessing them in the typical way,” Brisbin said. “As someone who’s relatively new to the organization and seeing how it’s functioning, they really have created a good community that are there for each other outside of just coming together to play like hockey. We’re trying to expand by involving the players to really be a part of the organization, to assist with outreach, fundraising, the things that will kind of make it be more of a self-sufficient program too.”

Many adaptive leagues can require a lot of travel

Ford got involved with the founding of Boston I.C.E. in September 2018. Her youngest son, 16-year-old Gavin, has spina bifida and uses a wheelchair. Gavin has always played adaptive sports, Ford said, but many of the leagues — such as her son’s adaptive basketball league over two hours away in Connecticut — require a lot of travel away from the family’s home in North Reading, Massachusetts.

Not only that, but these leagues catered to youths with cognitive disabilities that Ford said didn’t fit her son’s needs. What he wanted was a competitive team nearby for athletes with similar physical disabilities.

So Ford and her family helped found Boston I.C.E. Storm. She has been the president since then, drawing on her husband’s experience with standup hockey and the family’s connections in the hockey world.

She said the league has been meaningful for young athletes with disabilities like her son.

“He’s like any other 16-year-old,” she said. “He just happens to be on wheels. … It limits his opportunities for lots of things. (I.C.E. Storm) is bigger than the sport. It creates an opportunity where (players) can be their authentic selves.”

The players on Boston I.C.E. Storm vary in gender and age (from 15 to 52), but travel across New England in pursuit of a common love of hockey. Boston I.C.E. Storm has about 14 to 15 players on its roster now, said Tom Drago, a member of the board of directors and one of the founding members of Boston I.C.E. Storm. Practices happen each Saturday at 6:30 a.m. at a rink north of Boston in Merrimack, Massachusetts.

“Our goal is to include as many people as possible,” Brisbin added.

Sport is easier on the knees than non-adaptive hockey

Drago, who is based in New Hampshire, also got involved through his son who has spina bifida and has been playing ice hockey for over 15 years. While Drago primarily helps off the ice, he has played himself when the team needs a goalie. (He’s found the sport is easier on his knees than non-adaptive ice hockey.)

“It grew on me,” Drago said. “I really enjoyed doing it, so I stayed in net. … It’s great. It’s a great bunch of people. The whole family gets involved so it’s a good experience.”

The rules for sled hockey are similar to standing hockey with some modifications given the slight difference in nature and equipment. But otherwise, the sport has given disabled athletes the chance to stay active.

Brian Bardell, who lives in Northbridge, Massachusetts, has been playing on the team since he helped with its founding in 2018. He now serves as the team captain.

Bardell got into ice hockey in 2015 after he had his leg amputated due to cancer. Knowing he was an athlete, his doctor recommended he try sled hockey as a way to continue playing sports while accommodating his amputation.

“He knew I needed that outlet,” Bardell said. “When cancer came about and I knew amputation was a reality, that was one of the main things that sunk in the most. … I didn’t know what to do without sports. (Sled hockey) made a world of difference. I became an athlete again…Sports is a huge part of people’s lives post-trauma and even people born with a disability. It’s empowering to them. These types of adaptive sports give that possibility back.”

Working with the team has allowed Brisbin to expand his professional knowledge base.

“I’m fortunate that they’ve welcomed me and kind of allowed me to work with them, even though it’s not my specific area of expertise,” he said.

And having someone with Brisbin’s background in physical therapy has been a huge improvement for the team, Bardell said.

“I’m just that guy that’s accident prone,” he said. “Having a physical therapist in the docket is just monumental. Luke is just an amazing person. He didn’t ask to be on the board. We asked him. That shows his character. He’s such a great person. Those types of people come around rarely to organizations like ours. When they do…we don’t like to let that go.”

Erin Kayata is a Northeastern Global News reporter. Email her at e.kayata@northeastern.edu. Follow her on X/Twitter @erin_kayata.