Efforts to limit fast-food near homes need rethinking, Northeastern researcher says

Policies focused on food swamps – or areas with a high proliferation of unhealthy food choices – near homes is less effective than targeting other areas where people eat. AP Photo/Nati Harnik

Amid an obesity epidemic in the United States, you may have heard of efforts to eliminate “food deserts,” or areas with few healthy food options, and limit fast-food chains near where people live.

But research from Northeastern University suggests a new approach.

“Most of the fast food in this country is consumed far away from home,” says Esteban Moro, professor at the Network Science Institute at Northeastern University. “This means that if we want to address the problem of unhealthy foods in our diet, we should be talking about what happens when we leave home.”

“Effect of mobile food environments on fast food visits” was published March 14 in the journal Nature Communications.

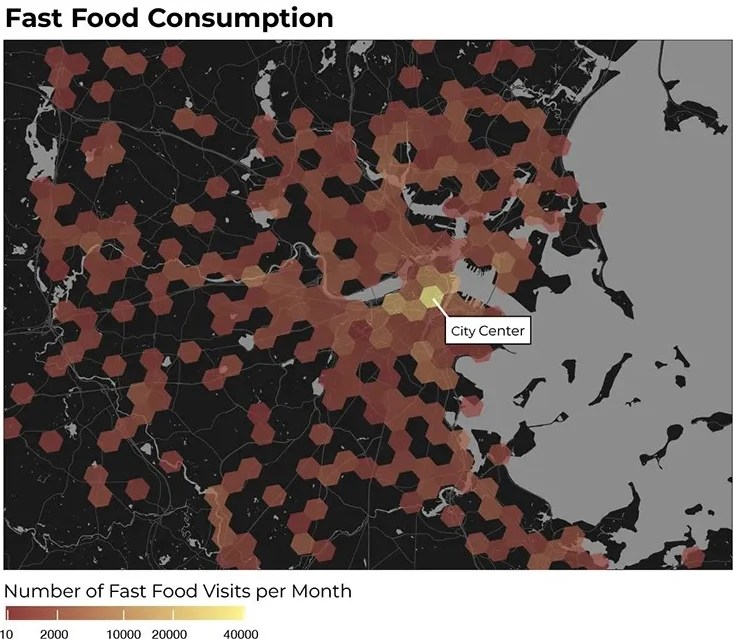

In the study, Moro and colleagues from the the University of Southern California and Massachusetts Institute of Technology examined mobility data from 11 American cities that showed 62 million people’s visits to fast-food outlets.

The researchers found that people traveled an average of 4.3 miles to get fast food, compared with only 2 miles to get groceries. Moro said an interesting finding in the study was that no particular socioeconomic demographic consumed more fast food than another.

“Thus, food choice is influenced by the food environments people are exposed to as they move through their daily routines, mostly far away from home,” Moro says.

The researchers also found that influence to be very strong.

For instance, the study found that visiting areas with 10% more fast-food outlets increased the probability of eating fast food by 20%.

“This suggests that the more we encounter fast-food options as we go about our daily lives, the more inclined we are to indulge in their offerings,” Moro says.

But Abigail Horn and Kayla de la Haye, researchers in the study at USC, point out that most policies to eliminate food deserts and food swamps, or areas saturated with fast-food outlets, have predominantly focused on residential neighborhoods.

These interventions — which included a $270 million investment by the Health Food Financing Initiative (leveraged with $1 billion in other financing) to support healthy food retail in underserved neighborhoods since 2010; as well as “fast-food bans” in Los Angeles — have also been ineffective, studies have found.

Featured Posts

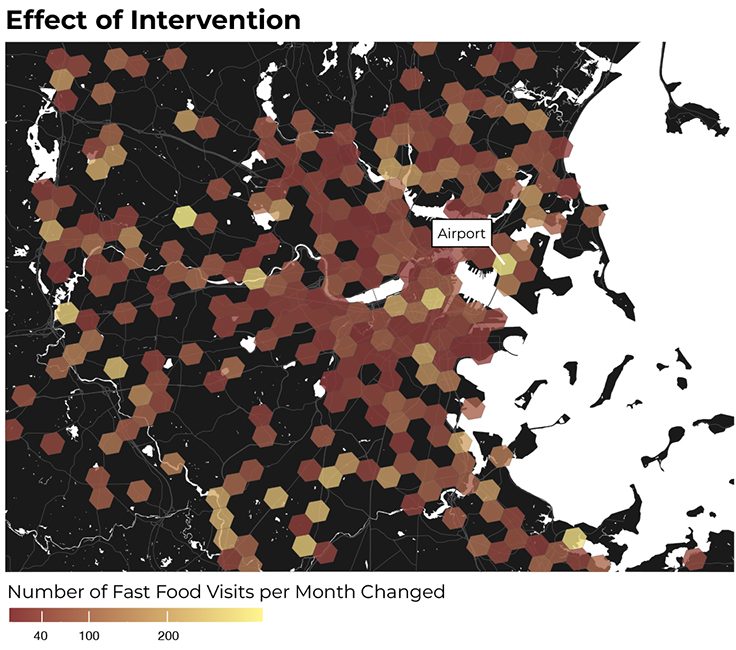

So, instead of focusing on neighborhoods around the home, Moro and colleagues recommend implementing these interventions in places that meet three criteria: places where most decisions about food outlet visits are made; areas where fast food is more prevalent than healthier food; and, more importantly, places where visitors’ food decisions are most susceptible to the food environment.

Moro gave the example of an airport terminal: it’s a location where lots of people eat; where fast-food options proliferate; and where people must choose food from among the available options (unless you want to go through security again).

“The study found that by selecting those optimal locations, we can devise interventions that could have two-times to four-times larger effects on unhealthy food choices than traditional interventions that alter food deserts or food swamps around residential areas,” Moro says.

Other potential places for intervention include areas like shopping centers, office parks and other travel hubs, according to researchers.

“What we found is everybody’s consuming fast food,” Moro says. “And the environment we are exposed to is conditioning the food that we eat.”