Will large language models survive the coming AI innovation?

For all of the hectoring and fearmongering coming from a small-but-vocal group of AI naysayers since the start of ChatGPT’s iterative rollout, there’s been impressively little to fear.

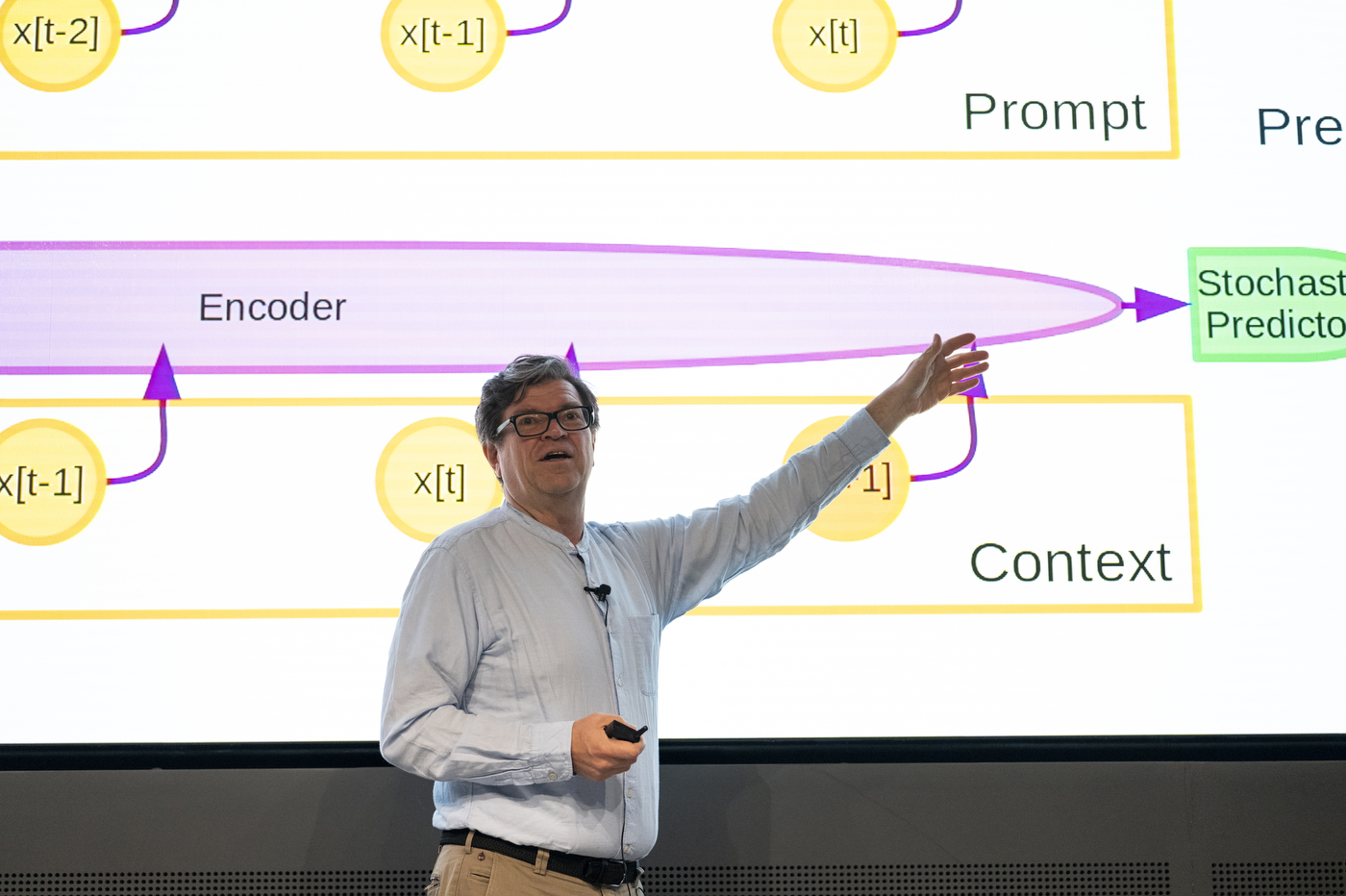

So says Yann LeCun, chief AI scientist at Meta AI, and one of the purported “godfathers” of AI and deep learning. LeCun told an audience of Northeastern students, faculty and staff this week that the leading large language models (LLM) are far from being able to “reason and plan” on the order of human beings and other animals. Large language models are programs that use deep-learning algorithms to generate text in a human-like fashion, such as ChatGPT.

“I’m always interested in the next step and how we can make machines more intelligent,” LeCun said.

That theoretical next step in developing more autonomous, intelligent machines, according to LeCun, might involve something called a “world model,” an architectural framework for how AI-based systems can move beyond natural language processing capabilities to “perceive, reason, predict and plan” according to parameters that are rooted in the real world.

The essence of such a model is an ability to make predictions based on real-world training, LeCun said—a far more technical machine learning process than the “auto-regressive” neural networks that make up LLMs.

Compared to tasks such as driving a car in the real world, “text is easy,” LeCun said. “Language is simple.”

But for the time being, no one working in the AI space can deny that we’re on the cusp of sweeping societal change and economic transformation presaged by the widespread presence of use of AI chatbots, says Usama Fayyad, executive director for the Institute for Experiential Artificial Intelligence.

“From a research perspective, these tools might be considered boring by some researchers in the field, say in 5 years when newer better solutions emerge,” Fayyad told Northeastern Global News. “But they will be significantly impactful economically in accelerating knowledge worker productivity.”

Experts like LeCun, who take a slightly more critical stance in relation to LLMs, point to the technology’s penchant for hallucination. Anyone who’s used ChatGPT for even a short period of time can attest to the seemingly random inaccuracies that can result when it is prompted with questions or requests that it cannot fulfill based on its training.

“This predict-the-next-word-in-a-sequence algorithm spews out sentences that sound eloquent and look natural, but it has no understanding whatsoever of what it is saying,” Fayyad said.

Demystifying what these chatbots are actually doing—how they function—may well alleviate public concern. Fayyad suggests they’re little more than glorified auto-complete bots—albeit, programmed with potentially hundreds of billions of parameters. But from afar, their bedazzling processing power and strikingly coherent responses to queries can lead many to a distorted view of the technology’s so-called “intelligence,” he said.

“Lots of people are confusing the eloquence and fluidity in natural language text generation with intelligence,” Fayyad said. “It’s just another tool that companies, individuals and students will be using in a very organic way.”

Fayyad emphasized that if chatbots become a feature of the workplace, higher education and industry more broadly, human steering will become increasingly vital.

“You actually need humans and a lot of effort to figure out what a good training data set is and how accurately it is pre-labelled,” he said. “Human intervention and feedback, that is, to keep these things from going completely irrational on us.”

LeCun is not convinced that the existing generative AI models can be sustained without significant crowdsourced manpower.

“It’s clearly very expensive to curate data to produce a good LLM, but I believe it’s doomed to failure in the long-run,” LeCun said. “Even with human feedback … if you want those systems ultimately to be the repository of all of human knowledge—the dimension of that space—all human knowledge—is enormous, and you’re not going to do it by paying a few thousand people in Kenya or India to rate answers. You’re going to have to do it with millions of volunteers that fine-tune the system for all possible questions that might possibly be asked. And those volunteers will have to be vetted in the way that Wikipedia is being done.”

“So think of LLMs in the long run as a version of Wikipedia plus your favorite newspapers plus the scientific literature plus everything else—but you can talk to it,” LeCun said.

LeCun and Fayyad were in conversation during a fireside chat on Wednesday hosted by Northeastern University’s Institute for Experiential AI as part of an ongoing distinguished lecture seminar series. Fayyad said he and his Northeastern colleagues are laser-focused on “getting to the base truth [of AI research and development] and slicing through the hype.” Boston area CEOs and and venture capitalists attended the event, held inside the auditorium at Northeastern’s Interdisciplinary Science and Engineering Complex.

LeCun’s lecture, titled “From Machine Learning to Autonomous Intelligence,” comes at a moment when society is reckoning with the potential of AI technology to upend industry, the workplace, health care and education. Much of the public fervor surrounding AI is focused on the role of generative AI in ushering forth those transformations—along with other potentially unforeseen ones.

It’s the latter possibility—that generative AI may also lead to unpredictable and even dangerous outcomes for human societies—that’s elicited a vocal reaction from a community of techno-naysayers, including LeCun’s own colleagues. They’ve warned that AI systems could be misappropriated, used for harm, outsmart human beings and result in devastating job loss. Both LeCun and Fayyad suggest these fears are overblown, pointing to the current state of AI algorithms.

The chat also comes about a week after OpenAI CEO Sam Altman testified before Congress about the need for effective regulation of the emerging technology, while also addressing the specific fears about his company’s hugely popular ChatGPT. Asked about his deepest fears about the trajectory of such technology, Altman said: “If this technology goes wrong, it can go quite wrong.”

When Fayyad asked LeCun what he would have said to the congressional committee had he been invited, LeCun replied that “claims that generative AI could lead to the destruction of humanity are preposterous.”

Tanner Stening is a Northeastern Global News reporter. Email him at t.stening@northeastern.edu. Follow him on Twitter @tstening90.