Carla Brodley, Geoffrey Trussell receive lifetime fellowships to American Association for the Advancement of Science for exceptional contributions to their fields

Two Northeastern leaders recently received fellowship awards with the American Association for the Advancement of Science, a lifetime honor for their exceptional contributions to their fields.

Carla Brodley, dean of the Khoury College of Computer Sciences at Northeastern, and founding executive director of the Center for Inclusive Computing, was chosen for her outstanding national service towards diversifying computing, combined with broadly impactful research in the field of machine learning.

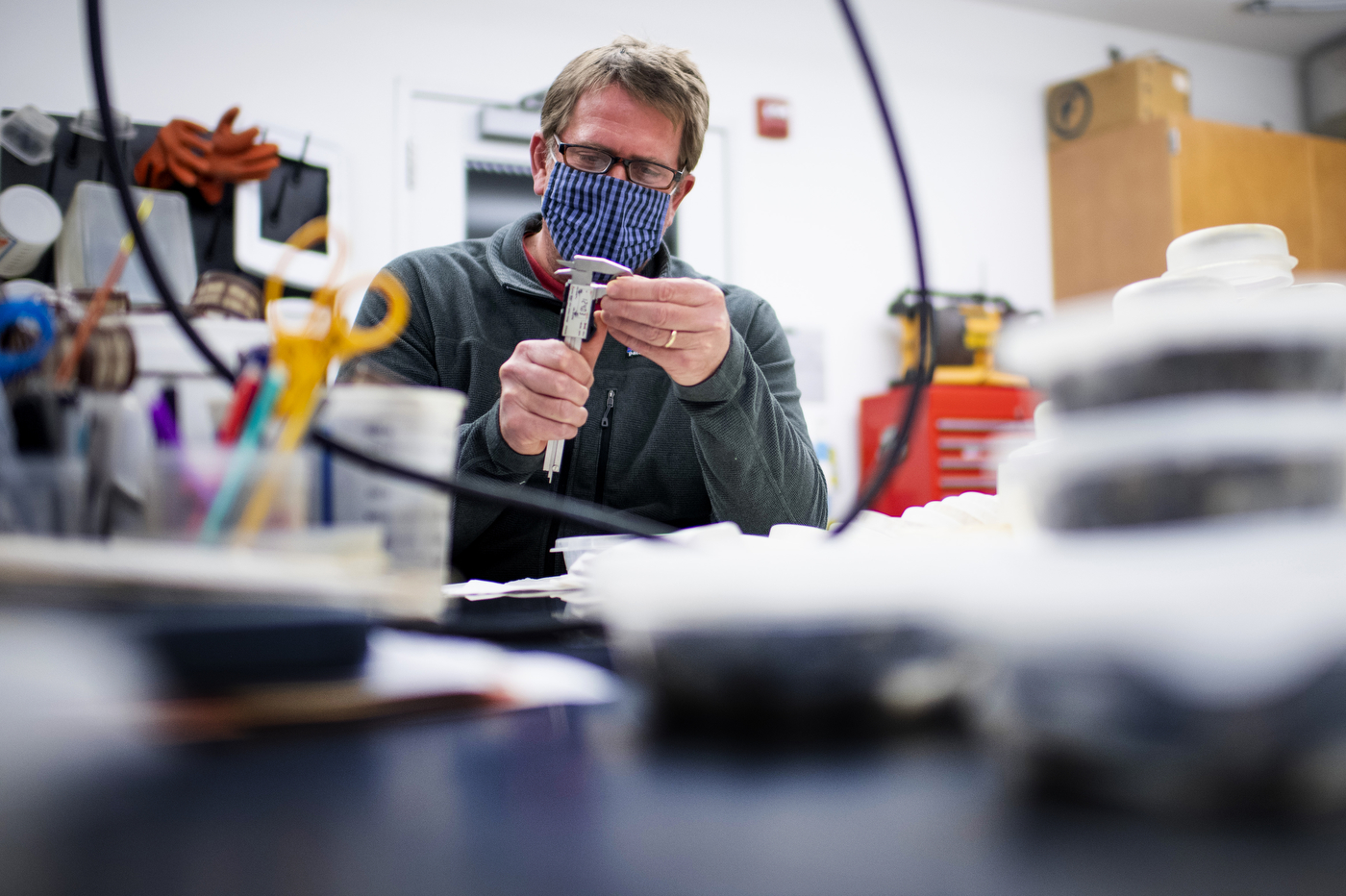

Geoffrey Trussell, chair of the marine and environmental sciences department and director of the Marine Science Center, was selected for his research combining ecology and evolution to understand the functional role of species in ecological communities.

Trussell and Brodley are not the first members of the Northeastern community to receive this fellowship. They join the ranks of university president Joseph E. Aoun, provost and senior vice president David Madigan, university distinguished professor of psychology Lisa Feldman Barrett, and university distinguished professor of biology Kim Lewis, to name a few.

“I’m thrilled to join such an exalted group of people,” Brodley says.

Brodley uses machine learning to make discoveries in the areas of science, engineering, and medicine while honing new machine learning techniques in the process.

“The best machine learning happens when you’re faced with a new area where machine learning hasn’t been applied,” she says. “You often end up having to invent something new.”

For example, Brodley worked on a project with Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston to predict whether patients newly diagnosed with multiple sclerosis would develop mild or severe cases—important information for determining the type of preemptive treatment patients should receive.

Multiple sclerosis medication can have serious side effects. “If you know you’re going to have a benign case, you’re not going to want to take the severe medications,” Brodley explained. “But if you know you’re going to be walking with a cane in two years, you might be more willing to accept the more drastic medications.”

Through the use of machine learning, Brodley and her team were able to analyze large sets of information on multiple sclerosis patients, helping them identify patterns of characteristics that indicate whether a severe case will develop.

Trussell’s research integrates theories from ecology and evolution, two disciplines that, until relatively recently, have worked in isolation from one another. He studies the reciprocal influence that ecological and evolutionary processes can have on one another.

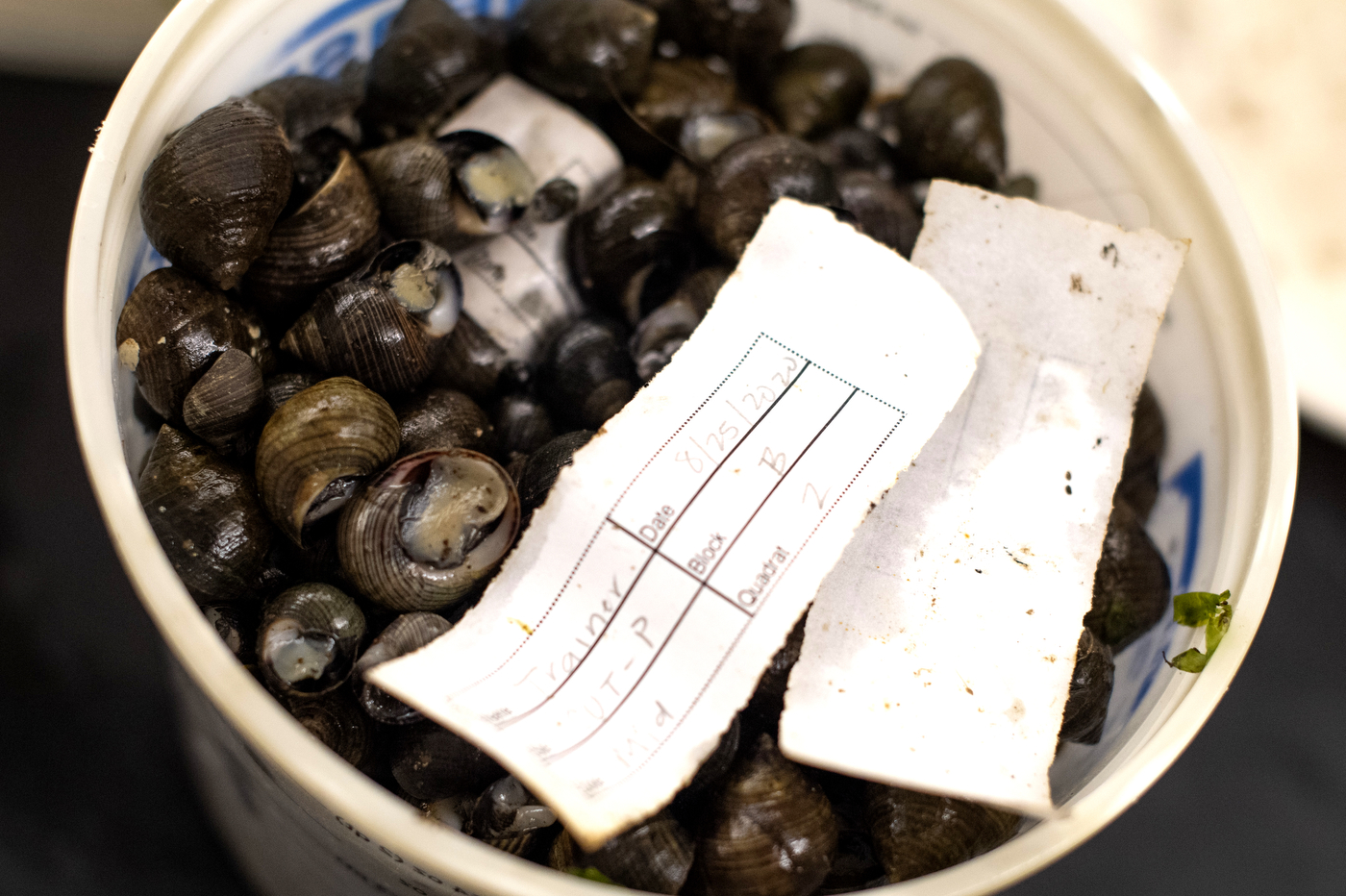

For example, Trussell studies how the arrival of an invasive crab predator to New England’s shores induced rapid physical change in snail shells. Early work showed that some snail species responded to this invasion by growing thicker and stronger shells and argued that such transitions reflect Darwinian, survival-of-the-fittest natural selection. But Trussell showed that simply exposing these snails to chemical cues produced by the crabs, not the crabs themselves, could induce them to develop thick shells in as little as 45 days.

This discovery helped to change long-standing views on the processes that shape morphological changes.

The heightened presence of the crabs also strongly affects snail behavior. This dynamic, called the “ecology of fear,” integrates the evolutionary calculus of the trade-off between eating and being eaten with the ecological consequences of those decisions. By eating less and hiding more, snails can determine the abundance of other species in the environment and change important ecosystem properties, such as energy flow through food webs.

Since graduate school, Trussell’s work has been inspired by a quote from the famed evolutionary biologist, Theodosius Dobzhansky—“Nothing in biology makes sense except in light of evolution.” This notion is more readily embraced by marine scientists today, but Trussell’s lab helped lead the way for this line of thinking with important tests of theory in the lab and field.

For Trussell, who one day hopes to be elected into the National Academy of Sciences, receiving this fellowship is an important first step, he says.

“It’s really flattering to be recognized by a group of peers, and frankly I wasn’t even thinking about receiving such honors when I was in grad school,” he says. “We’re trying to be global leaders in the area of coastal sustainability, so any recognition that comes to me or any of the other faculty and students in our department is great.”

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.