The descendant of the only German officers who survived a plot to kill Hitler tells her family’s fascinating story

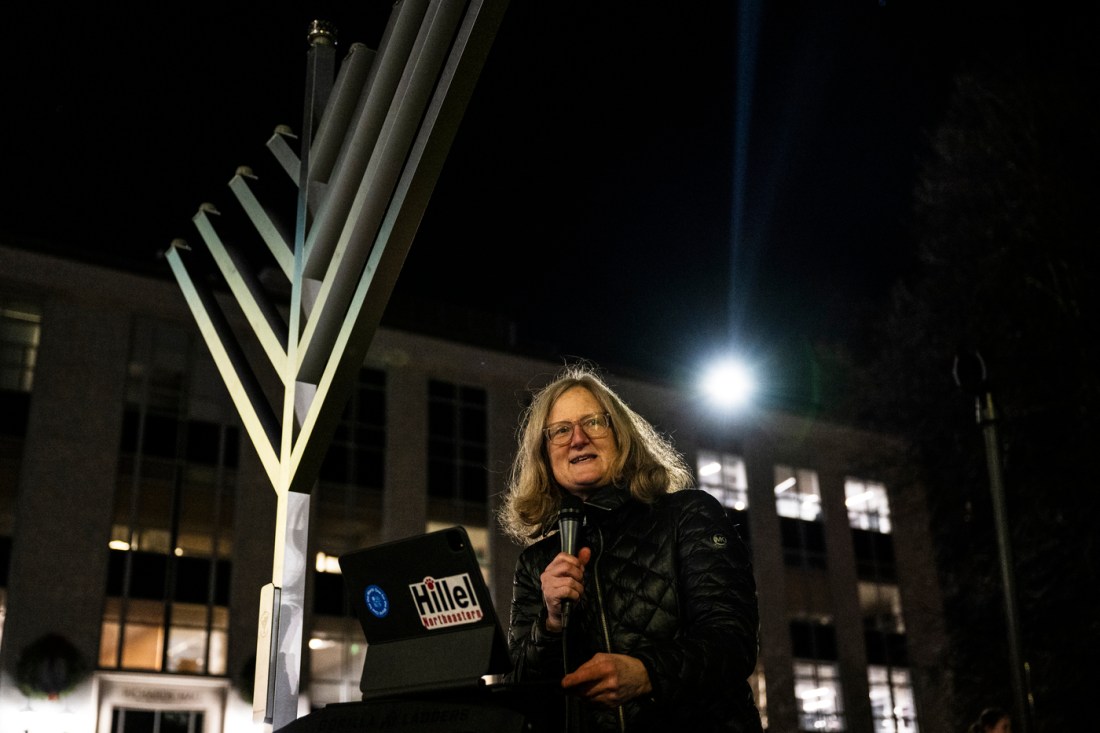

Northeastern Hillel’s Rabbi Sara Paasche-Orlow is descended from German resistance fighters, spies and post-war Nazi hunters whose stories of fighting against the Nazi regime impact her spiritual practice today.

The plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler on July 20, 1944, had failed. An ensuing military coup to take over the centers of Nazi power, so-called Operation Valkyrie, had been dashed. The Nazis were closing in on the Bendlerblock in Berlin, the headquarters for the German military and home to several officers involved in the coup.

Kunrat and Ludwig von Hammerstein-Equord, two brothers and officers who had been tapped for leadership roles in the government that would replace the Nazi regime, knew it was time to do or die.

Luckily, they knew this building like the back of their hands. The sons of Kurt von Hammerstein-Equord, the commander in chief of the German army prior to Hitler’s rise to power, the two brothers had basically grown up in the Bendlerblock. Rushing to a back stairway, they escaped the Nazis and fled.

Most of the others involved in the coup were not so lucky. More than 7,000 were arrested, including family members of those involved in the plot, and many were sent to concentration camps as political prisoners. Close to 5,000 were executed.

The Hammerstein-Equord brothers survived, but their story, and their family’s story, didn’t end there. Full of German freedom fighters, spies, Nazi hunters and even ministers, the story of this family is one defined by resistance and fighting against injustice in the face of insurmountable odds.

That flame is kept alive by the surviving members of Kunrat and Ludwig’s family, including their great-niece, Sara Paasche-Orlow, who, in a poetic turn of history, is a rabbi, and director of Northeastern University’s Hillel.

For Paasche-Orlow, her family history is never far from mind. It’s affected how she practices her faith, how she lives her life and how she views her very identity as a Jew descended from a German general who opposed Hitler from the very beginning.

“It has led me to really think deeply about war and violence,” Paasche-Orlow says. “My history in some ways makes me all the more open-eyed about these things and viscerally aware of the consequences. I visited with my great-uncles to the cell where their mother was kept in Dachau. These are very real impacts on people’s lives.”

This history of resistance comes from her father’s side of the family — although her mother’s side, American Jews, worked to provide sponsorships for Jewish refugees during World War II — and largely starts with her great-grandfather, Kurt von Hammerstein-Equord.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Kurt von Hammerstein-Equord and his wife, Maria von Lüttwitz, raised their seven children to be part of the cosmopolitan culture of 1920s Berlin.

The children might have grown up in the heart of German military culture, but they went to progressive public schools alongside Jews and had a “strikingly liberal, open way for a military family,” Paasche-Orlow says.

A renowned general, Kurt von Hammerstein-Equord was an unambiguous opponent of Hitler and the Nazis. His position was shared by many high-ranking members of the German military when Hitler rose to power. However, Hammerstein-Equord’s political and home life were more deeply connected than most, as he essentially raised a small army of resistance fighters of his own.

“My great-grandfather was basically still privy to a fair amount of information, so he would leave cryptic notes on his desk and [my grandmother, Marie Therese] would then see that X journalist was going to be arrested and would notify that person, sometimes even take them out of Germany into Czechoslovakia on her motorcycle sidecar,” Paasche-Orlow says.

Kunrat and Ludwig von Hammerstein-Equord followed most closely in the father’s footsteps, serving in the military and, to varying degrees, the military resistance and July 20 plot to assassinate Hitler. However, Kurt von Hammerstein-Equord’s wife and daughters were also deeply involved in the resistance, using their place in German society and proximity to German military command to undermine the Nazi regime, says Paasche-Orlow.

His daughters Marie Luise and Helga von Hammerstein had been long-serving members of the German Communist Party’s secret service and later operated as Russian spies, informing the Russians of Hitler’s political and military activities. Marie Therese Von Hammerstein Paasche smuggled Jews out of Germany during the early years of the Nazi regime.

After the failed assassination plot and coup, the von Hammerstein-Equord family was on the run. Ludwig and Kunrat escaped — the former into the Berlin underground, the latter to Cologne — while Paasche-Orlow’s grandmother, Marie Luise, had left with her husband for Japan, where Paasche-Orlow’s father was born. The other family members were held as political prisoners in the concentration camp at Dachau.

Editor’s Picks

“It wasn’t an easy time at all, although they were political prisoners — the family was still too prominent, it seems, to have been executed,” Paasche-Orlow says.

The end of the war was “in some ways another beginning” for her family, Paasche-Orlow explains, as they worked in the reconciliation process amid the ashes of the death and destruction wrought by the Nazi regime.

Kunrat von Hammerstein-Equord played a vital role in hunting down Nazi war criminals after the war, while Ludwig worked as a radio historian for the BBC and other radio stations. Their brother, Franz von Hammerstein-Equord, played an even more significant role after the war, and it’s his work that has had the most direct influence on Paasche-Orlow’s own.

The youngest son of Kurt von Hammerstein-Equord, Franz became a minister after the war and helped found Action Reconciliation Service for Peace, which sent young Germans to rebuild synagogues in Poland. Paasche-Orlow now serves as the American chair for the organization, doing her part to protect the very groups that were targeted by the Nazis.

The social justice and spiritual work done by the families of both her father and mother inspired her to enter rabbinical school in the 1990s. She graduated from the Jewish Theological Seminary in 1996 during the first decade of the school ordaining women as rabbis.

However, she was also attending seminary at a time when it was not ordaining or accepting of LGBTQ+ people, she says. Here she saw an opportunity to do what her family had done in Germany: stand up for what’s right. Flying in the face of norms, she chose to work at Congregation Beit Simchat Torah in New York City’s West Village.

“It was a 1,200-person congregation that was more than 50% HIV/AIDS positive. It was just a nightmare,” Paasche-Orlow says. “In that way, I said, ‘I need to go where I’m needed even if it is not in line with the current dicta of the setting.’”

“Growing up, this history of resistance and of questioning authority and of being on the right side of history was very important to my mother and to my father,” she adds. “Part of what brought me to rabbinical school and a leadership role in the Jewish community was a desire to be involved in social justice and in the power of community to help people.”

Now, as rabbi at Northeastern and director of Northeastern Hillel, she sees a whole new generation of people coming of age in a time when questions of American authoritarianism are front of mind. Like those before them, she sees young people eager but unsure of how to help in the fight against injustice.

Her family history, woven through her spiritual practice, is a reminder of both the cost and the necessity of individuals to do what they can in that fight, she says.

“I believe really strongly that we each have, in our own spheres, actions we can do to try to bring out the best we can in our societies and also to counter the forces that try to undermine humanity,” Paasche-Orlow says. “I do believe that we have to understand whatever power we have and try and figure out how to use that towards the common good and the good of the underdogs too or those that are most at risk.”