Northeastern to digitize archive of Boston legend Elma Lewis’ work, chronicling Black art and joy

For decades, Lewis was integral to expanding visibility and access for Black art and artists. In turn, archivists at Northeastern hope to bring her prized collection to even more people.

The Northeastern University Library is digitizing a treasure trove of archival materials from Boston legend Elma Lewis that will help shine new light on the city’s Black community and arts history.

Courtesy of a grant from the city of Boston, archivists from the library will be cataloging and digitally publishing materials from four of its collections that were originally donated by Lewis in the 1990s.

Who was Elma Lewis and what is her legacy?

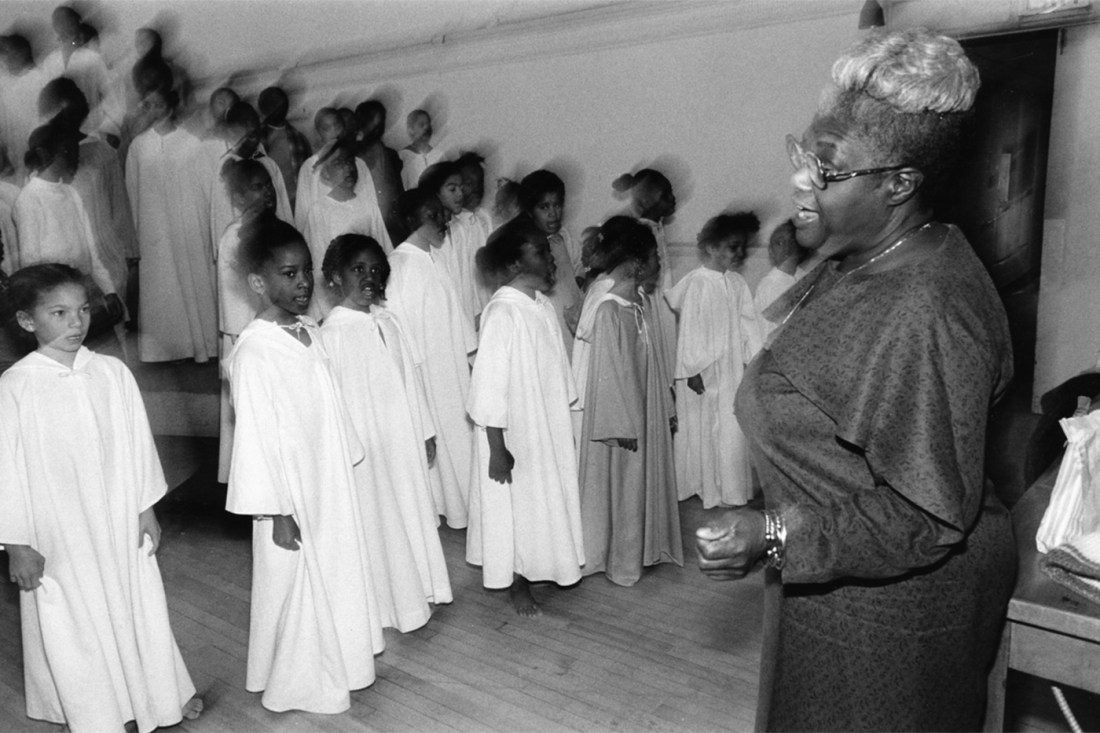

Lewis was one of the most significant figures in pushing for greater access to and awareness of Black art not only in Boston but nationwide. She opened the Elma Lewis School of Fine Arts in 1950, the National Center of Afro-American Artists in 1968 and the Museum of the National Center of Afro-American Artists in 1969.

“There are many, many things in the collections at Northeastern, and there are some jewels,” says archivist Gina Nortonsmith. “This is going to be one of those digitized jewels.”

“There’s been lots of interest in these papers,” Nortonsmith adds. “That’s one of the reasons we wanted to get them digitized: to get them more accessible. Just knowing how much … Elma Lewis meant to Boston, to Black Boston specifically, it’s remarkable.”

Archiving the life and work of a Boston legend

The four collections in Northeastern’s archives include documents from almost the entirety of Lewis’ life. Archivist Molly Brown describes them as “a Black art dynasty that came into the archives,” as three of the collections include archival materials charting the history and impact of the three institutions she founded.

During its peak, Lewis’ school enrolled 700 students and had 100 teachers. While enrollment started to dwindle in the 1970s as Boston desegregated its schools, Lewis used it as an opportunity to rethink music education and kickstart arts programs in Boston Public Schools as well.

Personal papers reveal scope of her influence

However, the Elma Lewis papers are the personal centerpiece of the four collections. Made up of Lewis’ personal documents, including her planner where you can see the meetings she had scheduled with Boston luminaries and handwritten notes alongside them, the papers show the scope of Lewis’ influence.

Editor’s Picks

“The National Center of Afro-American Artists and the Elma Lewis School of Fine Arts [were some] of the early Black arts organizations known in the states that had significant property to its name, that had physical space,” Brown says. “Both her curatorial mindset but also her pedagogical mindset of ‘this is Black art and it is globally interesting, it is globally necessary’ was really impactful.”

Preserving the cultural history of Boston

Despite Lewis’ impact, she is not immune to the passage of time and the changing face of Boston. The building at 7 Waumbeck St. where the Elma Lewis School of Fine Arts was housed doesn’t exist as it once did. Brown hopes that digitizing these records and providing more access to them “does invigorate a sort of preservation of these buildings’ past that were used and really celebrated by the Black community in Boston.”

Northeastern’s archival team also hopes that increasing access to these documents will benefit the generations of Black Bostonians, specifically Black artists, who went through Lewis’ programs.

“To have Black artists look at this collection and think, ‘You know what? My records matter. My records tell this story,’ to understand that value and import of recordkeeping either for yourself but also for your community knowledge to be highlighted is really exciting,” Brown says. “Having access to that information in a way that is abundant, like these collections, can be really important, especially as information is obfuscated, as information is not as accessible to others.”