Building community through design: Northeastern architecture class partners with Ethiopian church in Roxbury

Students in Alpha Arsano’s studio course reimagined Boston’s Ethiopian Evangelical Church designed to the needs of community members.

Boston’s Ethiopian Evangelical Church serves as a spot of worship for many in the Roxbury community. But the building itself — a former parking garage — is not necessarily ideally designed for its current use.

One Northeastern University architecture studio class worked to help change that, having spent a semester visiting the site, meeting with church members, and discussing their wants and needs for the building and then incorporating this into proposed designs with a focus on making the space more energy efficient while honoring the cultural history.

“In a typical studio, students might go and visit the site … and then spend most of the time in the studio,” says Alpha Arsano, assistant professor of architecture at Northeastern who led the course. “Here, there are some real, multi-layered challenges communicated by the church. Students need to spend time understanding those and trying to use them as the basis for their projects. It’s a very grounded, interactive process which would make it slightly different from a regular studio.”

The collaboration came about when Arsano, who attends the church, was approached by the pastor about a redesign. When she had the chance to teach an option studio, which can focus on anything the instructor would like, she decided to have students focus on this project and provide them with the chance for real community engagement.

This is the first time, she says, that an option studio course at Northeastern has had a community partnership like this.

“I was drawn in because of the type of project,” says Ethan Rogers, a fifth-year architecture major who took the class. “It had this community engagement side that I haven’t had as much exposure to that I thought was going to be really interesting.”

Over the course of the semester, students met with different members of the church community, from the elderly to young adults, and did different activities with them to understand their wants and needs from a potential redesign.

There was a learning curve for the students — who had to learn how to ask the right questions — and the community who’d never thought about things from the design side. Rogers said as a result, the students used activities and games to get the conversation flowing, such as having members create vision boards of their dream church.

“A lot of people have really good design intuition,” adds Joshua Webb, another fifth-year architecture student in the class. “It’s just a matter of expressing that. … We just had to get the conversation started.”

Students then had to take what they learned from these conversations and translate it into a design.

Editor’s Picks

During their meetings, Arsano says that the church members emphasized a need for a building that looks like a church and expresses Ethiopian culture and history.

Arsano says that students also tried to make the building more energy efficient in their designs by creating spaces that could rely on natural light and improve on the acoustics of the building. Members also wanted a space that could accommodate more churchgoers and an area for children in the church to gather and play.

Throughout the design process, the class invited different community members to the studio for consultation and had guest lecturers who discussed church history, representation, and how to design spaces for different communities that focus on their values.

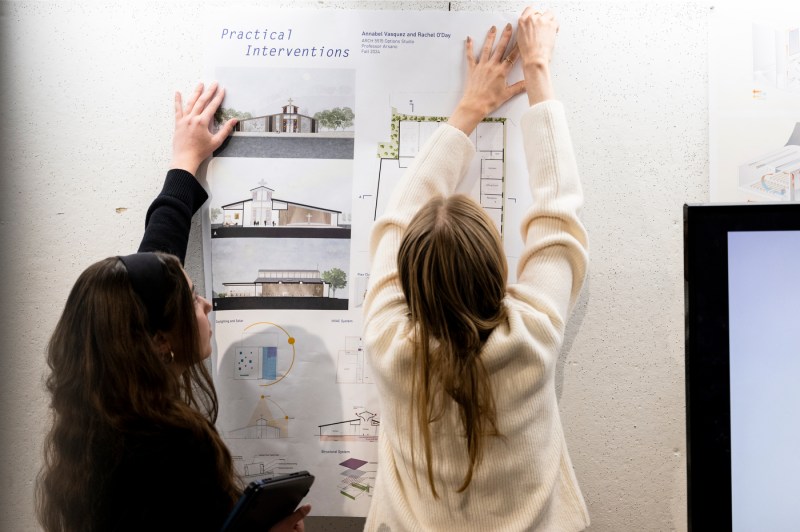

At the end of the semester, students presented their designs at the church for the members along with the estimated cost it would take to complete them. There were seven projects presented for feedback for the community. At the end, community members discussed what portions of the project might be feasible to implement.

“Now they have a breadth of options,” Arsano says. “The projects range from small interventions all the way to rebuilding the whole church.”

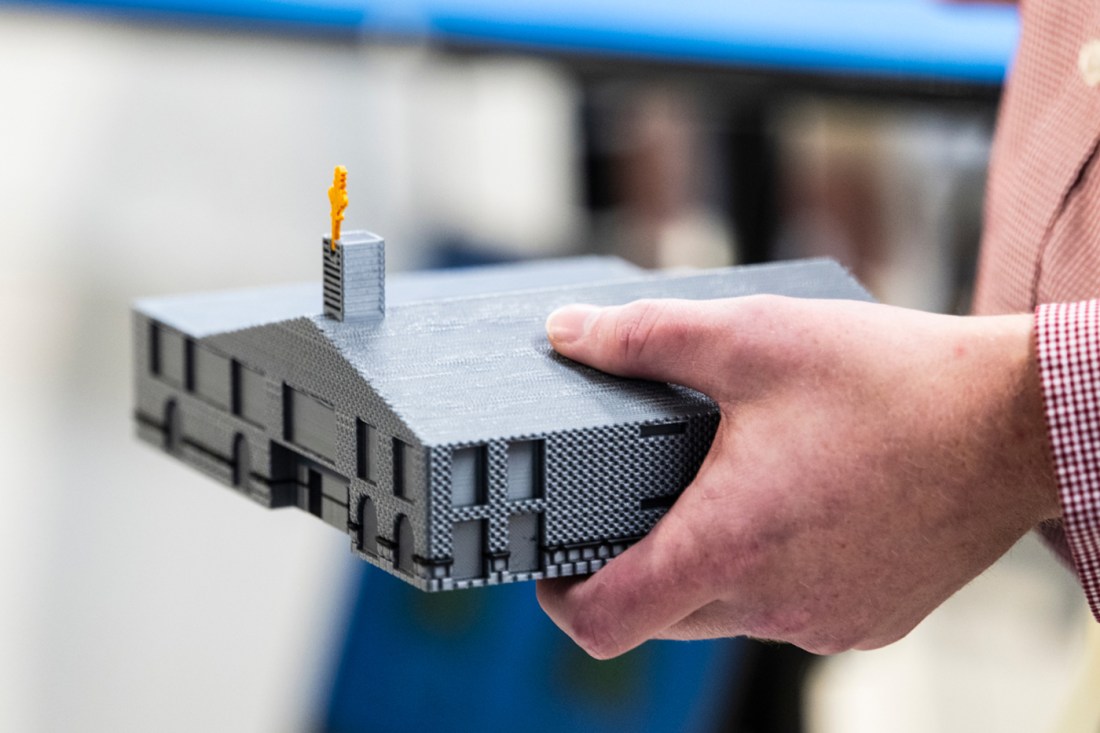

The final results varied in their designs. Rogers’ team came up with the idea of adding a second floor to enhance the existing space and a skylight to allow for natural light while Webb’s team proposed constructing a new building altogether. Other teams focused on creating spaces in the building that could be adapted for different needs while fifth-year architecture student Rachel O’Day and her team focused on acoustics.

“We really wanted to focus on having more minimal interventions to keep their budget in mind,” she says. “There was definitely a back-and-forth, which was different for us since we are normally designing from our own whims, but we constantly had to rely on these experts (and) the community to really understand where their priorities lie.”

After the class ends, Northeastern’s Solar Decathlon team, which aims to design and construct sustainable buildings around Boston, is going to take on the project and create a detailed design for it for an upcoming competition, one that will also address the engineering challenges of the buildings associated with the mechanical systems.

The class will provide all the findings and documents from their work. It could serve as a resource for fundraising and grants to fund the renovation.

Even as they move on though, the student says the experience taught them what it’s like to work with a community and design practical projects that incorporate cultural history.

“It is too often the case that designers prioritize aesthetic appeal and innovative design elements over functionality,” says fifth-year architecture student Noam Nissel. “In fact, the field of architecture — its genesis — stems from its ability to provide adequate shelter and fulfill the spatial needs of its users. This project reminded me of this fundamental — one that I plan to prioritize (and preach for) in practice.”