Northeastern’s neuroimaging lab empowers students with real-world brain research and innovative drug studies

Surgery after a basketball injury in 2014 left Northeastern student Sade Iriah hobbling around campus and managing her pain with prescription painkillers.

It also opened her to a whole new career — thanks to the university’s Center for Translational NeuroImaging lab.

“It was really just great timing,” Irish recalls. “I ‘crutched’ into class and the topic of the day was opioids, and it was just so applicable to my life — I just needed to know more. What are these opioids doing to me?”

A decade later, Iriah’s work with the CTNI lab has resulted in multiple journal articles focused on addiction and opioids and how drugs affect the body; three Northeastern degrees — a 2016 bachelor’s in behavioral neuroscience; a 2019 master’s in public health; and a 2023 Ph.D. in psychology with a specialization in behavioral neuroscience.

Those all led to her current job doing therapeutics research at a Boston area biotech company.

“It really did shape my career and what I’m doing now, and what I want to do in the future and my goals,” Iriah says of the CTNI lab.

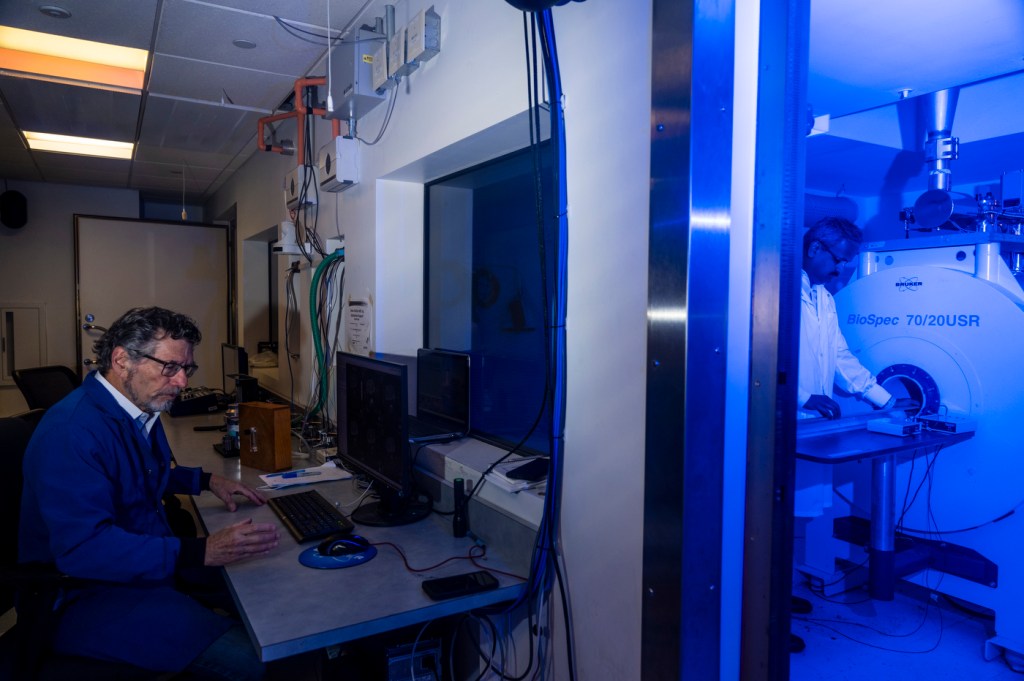

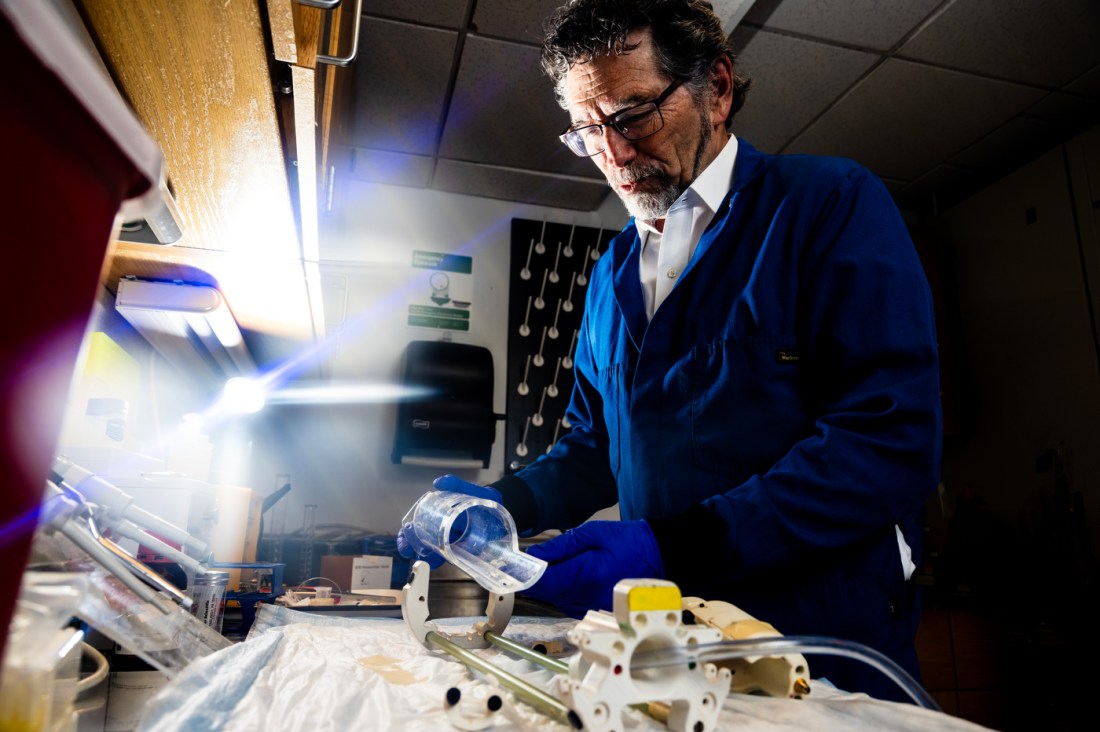

The lab, located in the Mugar Life Sciences building on Northeastern’s Boston campus, is directed by Craig Ferris, a professor of psychology and pharmaceutical sciences, and principal research engineer Parveen Kulkarni.

The lab centers around an MRI machine kept busy with independent student research, as well as research for biotech and pharmaceutical companies.

Ferris says he wants the lab results to be replicable on any other MRI scanner in Boston. But it’s also immediately apparent that this lab is a pretty unique place.

The lab specializes in non-invasive brain scans of rodents to study the effects of controlled drugs, repeated mild concussive injuries, disease progression and more.

Ferris notes that many of the drugs that the lab tests activate the central nervous system.

Reflecting the human experience is one of several guiding philosophies on which the lab operates — and it is showcased in some pretty innovative ways.

For instance, about five years ago, students came to the lab with questions about the long-term effects of cannabis and how it is processed by the brain.

Editor’s Picks

But in order to reflect the human experience, the researchers at the lab had to figure out a new way to deliver cannabis to the subjects during brain scanning.

“Ways that reflect the human experience,” Ferris says.

That’s a philosophy that guides the lab — that the work be “topical.”

“While there are so many questions that the students ask and studies that can be designed to further the investigation into those questions, some are more important than others,” Ferris says.

“We study cannabis because it’s being legalized around the nation, but little is known about its adverse effects. Hallucinogens are another big thing, being heralded as the next generation of therapeutics — really?”

The final — and most important — guiding principle is that students get to do real-world research. Students — after a proper vetting by Kulkarni — can come into the lab, take their own brain scans, and run experiments at all hours of the day.

Ferris says he believes that the lab is the only lab in the world where undergraduate students – over 40 undergraduates study and train at the CTNI each year, and many go onto medical school or academia – can independently work with an MRI machine on their own studies.

“Most imaging centers have a technician, and the technician will say, ‘well, what do you want to do, I’ll do it for you.’” Ferris continues. “That doesn’t teach these kids anything.”

Kulkarni says that giving students this real-world experience has several advantages, including providing students with a deeper understanding of imaging concepts, MRI physics, MRI pulse sequences, as well as enabling students to develop “critical thinking and problem solving” for MRI issues that may arise.

“No two MRI experiments are exactly the same,” Kulkarni says. “Experiencing the scanner firsthand builds confidence as individuals become more familiar and comfortable with the processes involved, preparing them for future challenges.”

A similar philosophy applies to data analysis, Kulkarni says.

“Students are taught concepts of imagining, they are trained to run different analysis software and some of them even help improve or write new analysis software,” Kulkarni says.

Undergraduate student Shreyas Balaji says that the lab complements his classroom learning.

“In classes I learn about how the brain works,” explains Balaji, who will graduate in May with a bachelor’s degree in behavioral neuroscience. “But here I can contribute in some way, hopefully, to the understanding of the brain.”

Recent graduate Lila Harris, whose research on the effects of different levels of LSD on adolescent mice was published in the journal Scientific Reports, says the real-world undergraduate experience was invaluable.

“I really didn’t think going into my senior year, or at any point, that I would be able to do the kind of research that I’m passionate about in my undergrad at all,” says Harris, who earned her bachelor’s degree in behavioral neuroscience. “I know that doesn’t happen all the time.”

Harris is now applying to Ph.D. programs to continue her research into the neurochemistry of psychedelic drugs and the potential to use such drugs as therapeutics.

“It’s become this kind of insane, pop culture fad, so I feel really motivated, and I think it’s really important that science keeps up with that fact,” Harris says. “I do think there’s a lot of potential for these drugs as therapeutics, but I don’t think that we’re at a point yet where we understand enough about them to use them as safely and to the highest degree of efficacy even where we are right now.”

Joshua Leaston, a 2020 Northeastern graduate, will graduate in a few months from Stanford Medical School with a specialization in using live image guidance to perform minimally invasive surgery.

He says that the CTNI was a “direct pipeline” to his career.

“When I was at the CTNI, I was able to really dive into what an MRI was and how that could be utilized to understand physiology,” Leaston says. “That foundation — and then subsequent steps to further embody what imaging actually was — was what made me so interested in choosing my specialty.

Iriah, meanwhile, is still thinking about her basketball days as she plans her future dreams.

“I would love to lead a research lab team that focuses on athletic health and athletic organizations and how to optimize wellness and how they perform,” Iriah says.

But beyond being celebrated by students for its technical accomplishments, its unique guiding philosophies, and its success launching careers, students spoke of CTNI most fondly as a supportive environment.

“I recognized that they had a lot of diversity and, as a Black individual myself, I felt that that was a major catalyst to helping me feel comfortable,” Leaston says. “That lab did an amazing job from day one in making me feel like I belonged there and that gave me a lot of confidence to help me become who I became, as not only a researcher, but in my future endeavors as becoming an academic.”

Iriah concurs.

“The lab environment was something that I also think was very important and integral to my growth because the questions were encouraged. The curiosity was encouraged,” Iriah says. “I was able to be my creative nerd self and I was able to just do the research that I wanted to, and when you have an environment like that, it is hard to leave that environment.”

“This is my first year actually since 2012, that I haven’t been in the CTNI,” Iriah continues. “It’s very strange.”