Northeastern students spend ‘life-changing’ two weeks working at a camp for people with disabilities, thanks to a professor’s connection

Kim Ho has been volunteering at Camp Jabberwocky for 38 years and now brings students with her to the Martha’s Vineyard camp as a way to teach them outside the classroom.

Growing up, Kim Ho heard her stepbrother, Ronnie, rave about his summers at Camp Jabberwocky, a camp on Martha’s Vineyard for people with disabilities. For four weeks every summer, her stepbrother would get to go horseback riding, visit the beach and bond with other campers.

When Ho was a teenager, she became a volunteer for Camp Jabberwocky, which is the oldest sleepaway camp for people with disabilities in America and serves campers free of charge. Her time volunteering sparked a lifelong passion for not only the camp, but for working in speech.

Ho is now an assistant clinical professor in communications sciences and disorders and has 38 summers volunteering at Camp Jabberwocky under her belt, befriending many of the campers over the years. Upon joining Northeastern three years ago, she decided to give students the opportunity to volunteer at the camp, hoping the experience would spark the same inspiration in them as it did for her.

“It’s really become a Northeastern thing,” Ho said. “The students write testimonials for me and one said it was life-changing for her, that it completely changed what she thought she wants to do and how she thinks about being a speech pathologist. You learn how to take care of people for an entire two weeks and their perspective about how it feels to have a disability. They can’t give you that in a classroom.”

Over the last three summers, Ho has brought a mix of about 24 undergraduate, graduate and Ph.D. students to Camp Jabberwocky for two-week rotations. During this time, students are assigned a camper and work with them 24/7, living in a cabin with them, providing them care and helping them through camp activities.

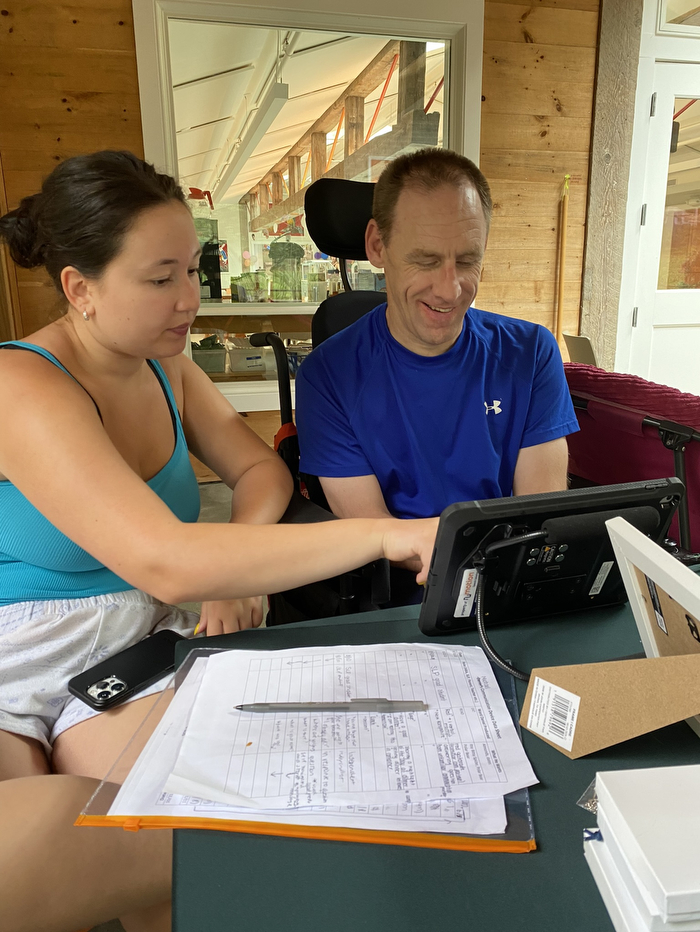

The camp was originally for people with cerebral palsy, but now takes campers with a range of conditions from autism to those with traumatic brain injuries. Many of them are non-speaking and use alternative forms of communication.

Students participating are trained in specialty areas necessary for caring for the campers, such as working with a feeding tube and driving a van for transport. Ho said they also learn about their camper’s individual needs over the course of the two weeks, whether it’s managing sensory issues or learning how to communicate with someone using an eye gaze device.

“It’s absolutely exhausting,” Ho said. “But I prepare them for that. I say get ahead with all your coursework, rest up and then … I supervise them 100% of the time. Then I start to pull back slowly when they get more confidence. It’s amazing to me how in two weeks, their skill and confidence levels (grow).”

For the campers, Camp Jabberwocky offers fun and connection without the worry of paying tuition.

“You can’t pay for this level of care,” Ho said. “People only go because they love it. I’ve become really close friends with many of the campers and get together with them throughout the year. Many campers will email me, call me, text me throughout the year. It just becomes the highlight of their year and they look forward to it.”

Emily Hartford, a second-year student in Northeastern’s masters of speech language pathology program, was familiar with Camp Jabberwocky from her visits to her grandparents on Martha’s Vineyard; she would see campers in the island’s annual Fourth of July parade. So applying to volunteer was a no-brainer.

Mornings at Camp Jabberwocky are usually spent in classes while afternoons are for the beach. There are different activities offered each night, Hartford said, whether it’s dancing or watching fireworks.

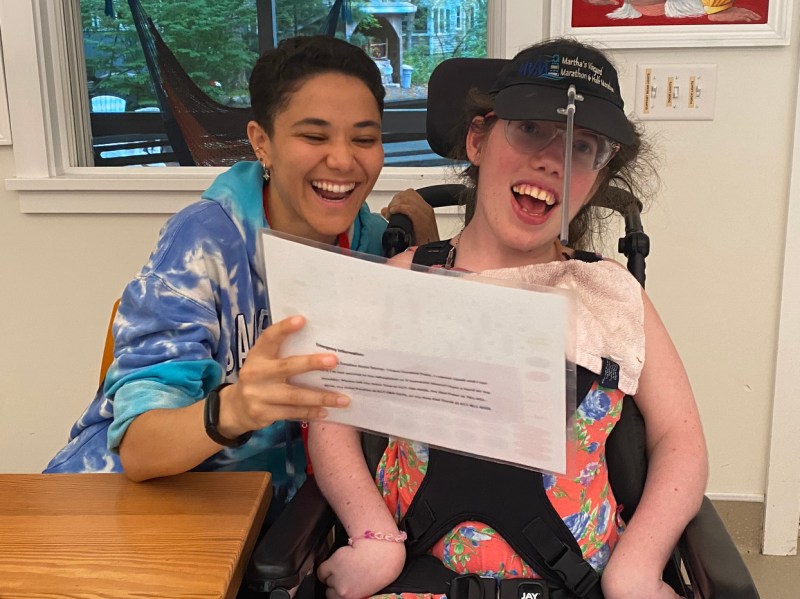

Over the course of her two weeks, Hartford worked with two different campers who had different speech modalities, including a laminated communication board where the camper could point out what they wanted. Working with the campers allowed Hartford to see what their lives were like, something she couldn’t gain working in a clinical setting.

“Being able to be with the campers doing day-to-day tasks, getting food, eating, communicating wants and needs, anything like that at any given point during the day, was eye-opening,” Hartford said. “It’s something that I truly appreciate. It’s beneficial to be focused and working on speech, but this is what you’re doing in the speech session and applying it in a real-world setting.”

Analise Castillo, another second year in the SLP program, was drawn to the camp for the opportunity to both volunteer and expand her mindset as a speech pathologist. She spent two weeks working with a camper with cerebral palsy who uses a wheelchair and a communication board where she would point at what she wanted to communicate.

“Something that I took away from camp that I will absolutely be taking into my own practice as a speech language pathologist is everyone’s individuality and unique needs,” Castillo said. “Before coming to camp, my view of disability was a bit more one-dimensional. After living with a whole bunch of people with a really wide range of strengths and challenges and abilities and disabilities, it became clear to me how unique everyone was, and there is a lot of beauty in that.”