Can James Earl Jones’ triumph over stuttering inspire others?

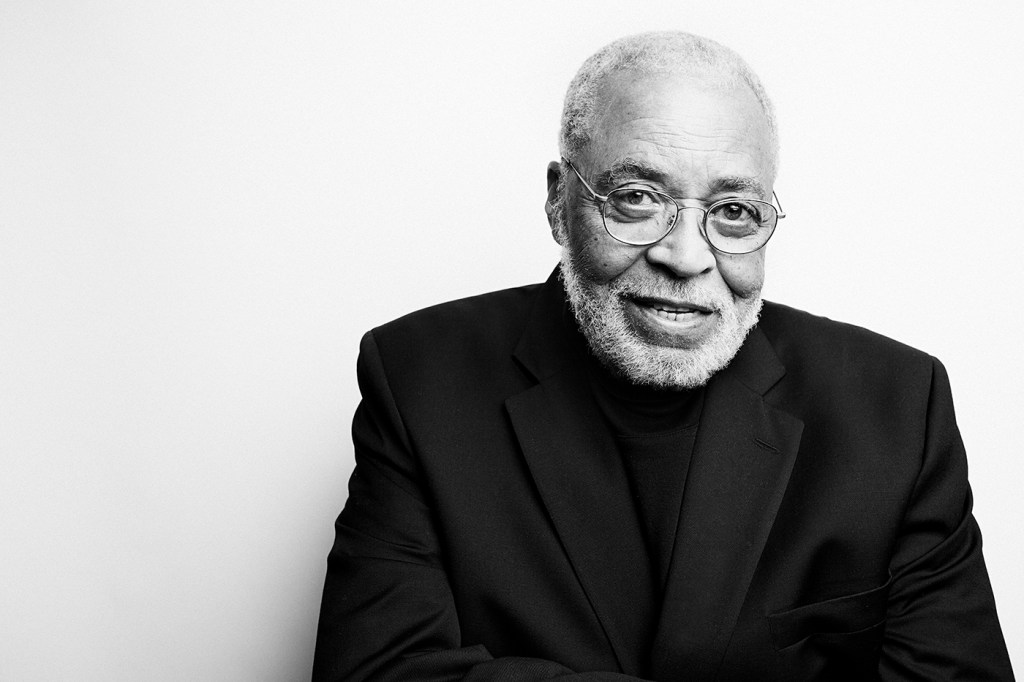

Legendary actor James Earl Jones, who died this week at the age of 93, is most remembered for his iconic, baritone voice.

But did you know he had a stutter?

In fact, his stuttering was so severe as a child that he barely spoke and was essentially mute from first grade to his freshman year of high school. That’s when a teacher had him read poetry in front of class, which helped him get a handle on the condition.

The experience also inspired him to pursue a career in the arts, eventually leading him to worldwide fame and recognition.

Northeastern University speech experts say Jones’ story is one of inspiration and highlights some of the strategies those who stutter can implement to manage the condition.

“When you have someone who was known for his voice be able to say, ‘I am someone who stutters, and look what I was able to do with my career,’ that’s great,” says Caren McDonough, an assistant clinical professor and clinic director of the Speech-Language and Hearing Center at Northeastern University.

“I think it’s incredibly important that they share that information, so that younger people who are dealing with this can say, ‘I can be anything I want to be,’” she says.

Doctors still don’t know why some individuals develop a stutter, but genetics can sometimes play a role, McDonough says. Additionally, the severity of a person’s stutter and its emotional impact can vary. It is estimated that about 80 million people around the world stutter, according to The Stuttering Foundation.

Featured Posts

Jones chose to mostly not speak as a child, but that’s not a universal experience for everyone who stutters, McDonough explains.

“There are some people who are comfortable stuttering openly, and then there are people who do get very quiet, especially in certain situations,” she says. “They may not raise their hand in school. They may not go up and ask for things. I hear a lot of times people won’t order what they want in a restaurant because certain words will be difficult for them. There are so many levels to it.”

Clinicians have a number of strategies they use in helping support people who stutter, and the goal of treatment is not to cure the people of their stutter, but help them develop ways of managing it, McDonough says.

Jones reciting poetry in front of his class was an effective way of managing and improving his stutter as it required him to face the fear of speaking in front of an audience, McDonough explains.

“For anybody who has to face a fear, the more you do it, hopefully the less difficulty you’ll have with it,” she says.

Additionally, poetry and music require us to use a different part of our brain than speech which can be helpful for those who stutter, she says.

Hannah Rowe, a Northeastern professor in communication sciences and disorders, says we have come a long way in the 80-plus years since Jones first discovered he had a stutter, both in treatment and resources available.

She points to the National Stuttering Association as a valuable organization to turn to for information, guidance and support. It is also now easier to find local support groups, she says.

“There are now a lot of resources in place to help people become more desensitized and start accepting the stutter as a part of themselves,” she says.

“The change in therapy has been pretty dramatic over the years,” says Rowe, who teaches a graduate course on stuttering at Northeastern. “It really used to be focused on not stuttering, whatever we can do to not stutter. Now we’re all realizing that the act of avoiding the stutter can make the experience of stuttering harder.”