Northeastern researchers test well water in North Carolina, empowering communities with critical data

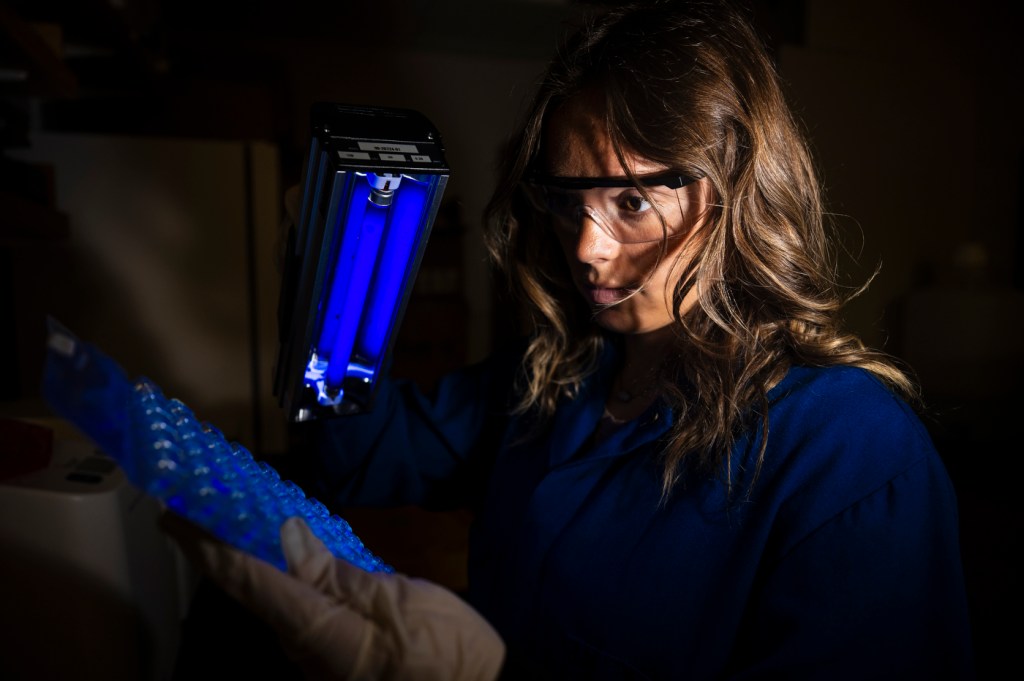

Ph.D. student Kyla Drewry went with a team of students to hand out sample kits to help residents in rural areas learn if their well water was safe.

Over 43 million Americans get their drinking water from private wells, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. However, there are no federal regulations in place to ensure the quality and safety of this water.

A research team from Northeastern University is using science to change that. Kyla Drewry, a third-year environmental engineering student working under assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering Kelsey Pieper, recently flew to North Carolina and led a team of other Ph.D. students on a research trip where they tested people’s private well water.

“It’s the responsibility of the well owner to test and maintain their water quality,” Drewry said. “The problem is a lot of people don’t know they have that responsibility or they don’t know how to manage their water quality. It’s an issue of access, knowledge and resources. One of the things we’re trying to do is make … people more aware of the risks and how to manage their water quality.”

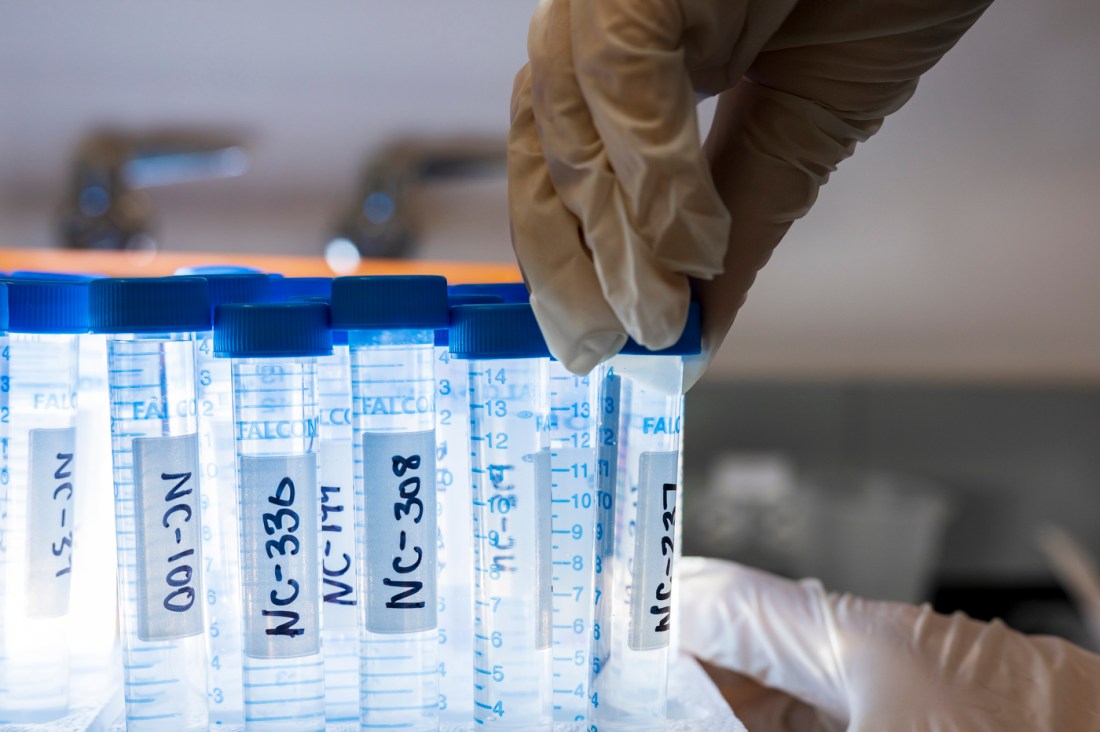

Drewery, along with a team of six other scientists — including other Northeastern Ph.D. students and a co-op student, Cassidy King — tested well water samples from Pender, Brunswick, Beaufort, Pamlico and Craven counties in North Carolina, where Pieper said one in four residents is on a private well and deals with contamination issues.

Getting people to come and collect sampling kits, do the sampling and then bring them back was going to be a challenge, Drewry said. She and her team worked with the local health departments to communicate their study on social media and in the newspapers. They ended up sending out 400 sampling kits and had about 250 returned to them.

Drewry and her team used these samples to collect baseline data on the well water, something that’s been difficult to establish due to lack of testing. They tested the water for bacteria like E.coli and for organic components like lead, arsenic, fluoride and nitrates. Participants were then informed of their results and how they could recover their system. The testing was free, which Drewry said helped draw in participants.

However, their trip coincided with Hurricane Debby. Storms like this can cause flooding and contaminate well water with fecal matter, whether it be from sewage overflows or North Carolina’s pig farms, Drewry said. According to Pieper, fecal contamination in water can be eight times higher after a storm.

Featured Posts

But Drewry said her team was still able to collect samples to establish baseline data for what well water looks like without a storm, as well as some information on the people in each household who was drinking the well water.

“We were at a 55% to 60% participation rate, which was honestly great for a cold campaign,” she said. “(Hurricane Debby) honestly ended up affecting our study in a positive light. We were able to get more interested. People heard about the hurricane and became more aware of the dangers (it posed) to their water quality and decided to get tested.”

Overall, 30% of the water tested had coliform bacteria, which indicates surface water intrusion and possible contamination. Three percent of the samples tested positive for E.coli. Metals analysis is still underway.

“This is the beauty of community science,” Pieper said. “Residents are being empowered with data. They’re learning about their systems. We’re giving them information on how they can make decisions about the water. We’re connecting with health departments so they can do mitigations. We are getting data from a community we don’t really have a lot of data on, so it’s giving us an understanding of what’s going on in their landscape. The students are getting an understanding of why we do science and are meeting the people they are actually helping. … It’s a mutually beneficial relationship we’re establishing.”

The trip was part of a project funded by a NASA Water Resources grant. NASA’s Water Resources program looks at problems with water management, including the safety of well water.

Drewry said many rural communities disconnected from urban centers rely on well water since they don’t have access to municipal water management systems. Historically, areas with certain racial demographics or that are low income have been excluded from these systems. But today, there’s little data on who relies on well water, making this work crucial.

Some people involved in NASA’s program are looking at how weather impacts well water quality, while others are studying people’s behaviors and perceptions around well water, Drewry said. The data collected on this trip will help establish a baseline for well water data.

“Research is obviously a priority here, but the primary purpose for me is making sure that the people who got their water tested have their results clearly communicated to them,” Drewry said. “They know what action they need to take, and they’re doing their best to make sure that they’re drinking water quality is safe.”

Science & Technology

Recent Stories

-

How did Netflix’s ‘KPop Demon Hunters’ take over the world and become a global phenomenon?

How did Netflix’s ‘KPop Demon Hunters’ take over the world and become a global phenomenon? -

Parasitic diseases researcher talks ‘flesh-eating’ screwworm infection after first confirmed human case in US

Parasitic diseases researcher talks ‘flesh-eating’ screwworm infection after first confirmed human case in US -

Who is Jane Boleyn? The real story behind the protagonist of Philippa Gregory’s new book, ‘The Boleyn Traitor’

Who is Jane Boleyn? The real story behind the protagonist of Philippa Gregory’s new book, ‘The Boleyn Traitor’