Lost letters of Mary, Queen of Scots, give up their secrets after 450 years, thanks to Northeastern historian

Associate professor Estelle Paranque is working to translate Mary Stuart’s medieval French into English after a team of computer scientists cracked the cipher she used.

LONDON — Despite 450 years having elapsed, the Tudor era is still releasing its secrets.

For decades, it has been thought that there must be missing letters written by Mary, Queen of Scots, that explain what happened in the years leading up to her execution in 1587.

And now, thanks to a team of computer scientists and historians, including Northeastern University associate professor Estelle Paranque, 50 letters have been uncovered, decoded and are being translated from medieval French into English.

Paranque says “everything falls into place” when reading through these letters that had been held in the National Library of France and cover a “very important” period in Mary Stuart’s life between 1578-1584, a time when she was in captivity.

“We always knew these letters in the archive existed but didn’t know what they were about and we were not sure that they were Mary’s,” Paranque says.

“There is a historian, John Bossy, who wrote a big book on conspiracies and plots under Elizabeth I. He said there must be letters that are missing because he was looking at all the [available] letters sent during that time and he said, ‘It just doesn’t make sense. There must be letters that are missing that we don’t have or that are coded.’

“And now, by decoding them, we know for sure, who sent them, who they were to — all of this. And they are the missing piece to so many questions.

“We were asking ourselves, ‘Why was this decision made on February 25, 1582?’ Oh wait! Now we have the letters from January 1582. This is going to tell you why that decision was made a month later. Everything falls into place.”

Letters put in historical context

The translated letters are due to be revealed by Paranque and her colleagues in a book published by Routledge in 2027. The academic work will also detail how the letters were deciphered and put the correspondence in their historical context.

The project started when codebreakers George Lasry, a computer scientist and cryptographer, Norbert Biermann, a pianist and music professor, and Satoshi Tomokiyo, a physicist and patents expert, were looking for new subject matter for their hobby.

Featured Posts

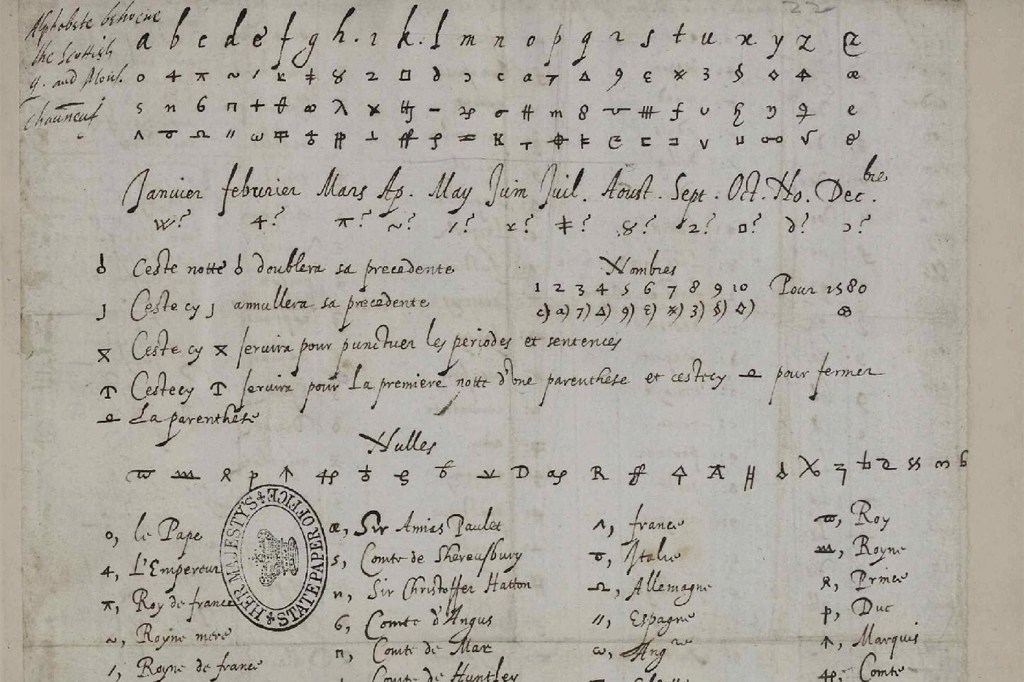

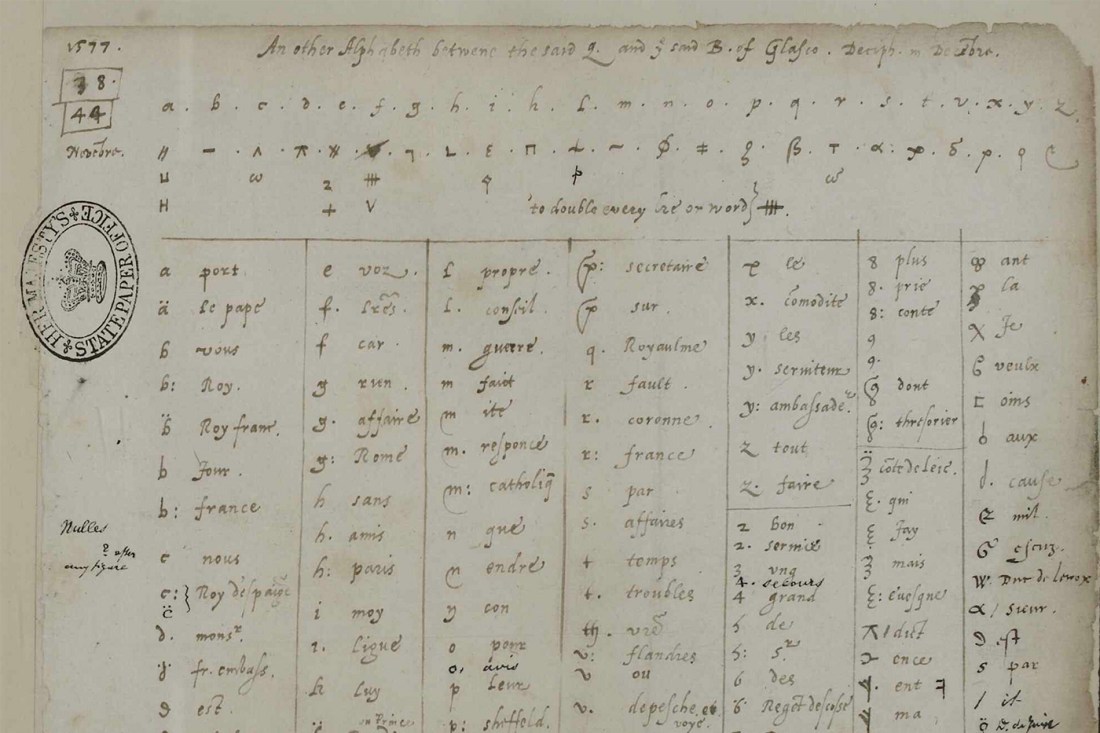

Applying computer and manual techniques to these cryptic letters in the French archives, they cracked the cipher Mary used when corresponding, with most of the letters addressed to Michel de Castelnau, the French ambassador to England between 1575-1585.

Mary’s reign as queen of Scotland, which started in 1542 when she was only 6 days old, had regular tribulations but the real trouble started in 1567 when she eloped with the Earl of Bothwell for her third marriage. Bothwell was thought to have been involved in the murder of Mary’s second husband, Lord Darnley — an accusation that caused the Protestant nobles to turn against her, imprison her and forced her to abdicate.

In 1568, Mary escaped and fled to England, seeking protection from her cousin, Elizabeth I, the queen of England. But Elizabeth viewed her relative as a threat due to some Catholic critics not recognizing her as the legitimate heir, given her father Henry VIII had divorced to marry her mother, Anne Boleyn. They instead believed Mary had a claim to the throne, being a descendant of Henry VIII’s sister.

Kept in captivity for 19 years

As a result, Mary was kept in captivity for 19 years and later implicated in the Catholic Babington Plot in 1586 to overthrow Elizabeth. She was tried and executed in February the next year.

During her imprisonment, Mary — who was brought to life by Saoirse Ronan in the 2018 film, “Mary Queen of Scots” — kept up correspondence with her allies in France, where she had grown up. She knew her letters were being read by Elizabeth’s close aide, Sir Francis Walsingham. But she used a cipher to send secret notes to Castelnau and a small handful of others.

It is known that Walsingham was able to attain a “comprehensive” leak of some of the correspondence and was able to decode them, meaning that seven transcripts of ciphered letters already existed in the British Archives. Their existence allowed the codebreakers to verify that the letters they had cracked were indeed Mary’s.

The computer scientists wrote an article, “Deciphering Mary Stuart’s lost letters from 1578-1584,” published in the Cryptologia journal in February 2023, that included a full decoded letter that had been translated into English, along with summaries of the rest.

But with 50 letters to work with, they needed assistance from experts who understood medieval French and could translate it into English to take the project further. That is where Paranque and her two academic colleagues, Alex Courtney and professor Michael Questier, came in.

Interdisciplinary project ‘very exciting’

Paranque — who has written extensively about the Tudor royal court — said working with computer scientists on an interdisciplinary project as revelatory as this one has been “very exciting.” She says for researchers delving into Mary, Queen of Scots, the ability to have access in English to the letters is “insane.”

.

The French academic says the findings have the potential to change the view of scholarship about Mary and how she conducted herself while imprisoned.

“The significance of this is twofold,” she says. “Firstly, there is the fact that these letters were mentioned by historians before, saying that it was the missing piece to understanding Elizabethean politics, to understanding what was going on with Mary Stuart and Elizabeth.

“And the second thing is the fact that because they are decoded letters … here we have the voice of Mary.”

The figure behind these coded letters is described by Paranque as a “totally different person” to Mary’s public persona.

“In the letters that are not coded, you have someone who whinges a lot, plays the victim, who seems a bit stupid. You have the damsel in distress,” she says. “With the coded letters, you have the new Mary. You have the Mary who is unfiltered, who doesn’t sugarcoat — you have a Mary who becomes the ‘mistress-mind.’”

‘She absolutely is intelligent’

“I’m not a Mary fan, and for a long time I thought she was stupid,” Paranque says. “She is not. She absolutely is intelligent. She is massively politically astute. I thought she made mistakes — she didn’t make mistakes; she made decisions.

“I thought that maybe she was a pawn in her family. She is not. She’s actually the one giving orders. And there is much more [in the letters] — her interest in Scottish politics, the way she does politics, the way she understands English politics.

“I thought she didn’t understand English politics. But the way she talks about Elizabeth, Leicester [Robert Dudley, Earl of], Huntington [Henry Hastings, Earl of], [Baron] Burghley [William Cecil, Elizabeth’s chief adviser] — it is insane.

“It is all unfiltered, you can see how smart she is, she knows exactly what they’re doing. And it shows us how well her network was working.”

In a discipline as old as Tudor history, not every historian will get to say that they worked on a major breakthrough in understanding what occurred in the highest echelons of power in the 16th century. But Paranque and her colleagues are right at the heart of exactly that.

“It does feel that way,” she says. “Only three historians right now have full access to this set of letters. They are very important and I cannot wait to share them.”