Should you be concerned about an Mpox outbreak in the US?

The new, deadlier strain of Mpox has spread in Africa and into Europe. A Northeastern expert says there will likely be cases in the U.S., but it’s not cause for panic.

The World Health Organization officially declared that a new strain of Mpox, formerly monkeypox, is an international public health emergency, the second time in two years the organization has elevated the status of the viral disease.

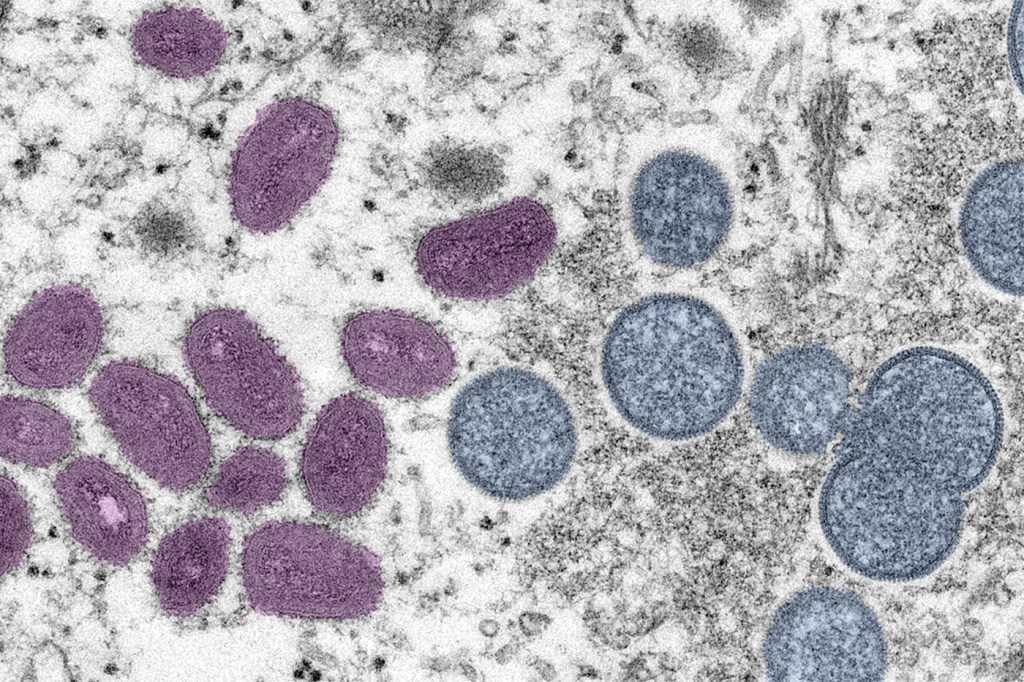

The clade I Mpox strain is different from the clade II strain responsible for the 2022 outbreak. Clade I is seemingly more transmissible and results in a more severe illness and higher chance of mortality if not treated.

The latest outbreak is occurring in central and eastern Africa, particularly in the Democratic Republic of Congo, which has experienced steadily worsening outbreaks since 2023. The clade I strain has since spread to Europe, with Sweden reporting the first clade I case outside of Africa on Aug. 15.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has reported no cases in the U.S. yet.

To date, there have been about 20,000 clade I Mpox cases in the DRC and 975 suspected deaths. Children account for two-thirds of the former and three-quarters of the latter, although the DRC noted that, like with the clade II outbreak in 2022, there has been substantial sexual transmission among gay, bisexual and men who have sex with men.

But how concerned should people in the U.S. be about this recent Mpox outbreak? What is the likelihood it will spread to the U.S. and just how much worse will the clade I strain be?

Neil Maniar, director of Northeastern University’s master of public health in urban health program and professor of the practice in the Bouvé College of Health Sciences, says there is a “solid likelihood” clade I Mpox will spread to the U.S.

In a globalized, interconnected world, it’s inevitable, he says, however, “the likelihood that this will become a pandemic like COVID-19 is very, very low.”

“I don’t think this is in any way, shape or form cause for panic or a cause for widespread concern among the general population,” Maniar says. “I think this is something health care practitioners and public health practitioners, whose job it is to be concerned about it, should be concerned about because this is our opportunity to really limit the spread as much as possible.”

Featured Posts

Part of the reason for Maniar’s cautious optimism is that there is already an effective vaccine for Mpox. The CDC recently stated that both doses of the Jynneos vaccine, which was used to protect against clade II, would still protect against the more severe clade I Mpox strain.

“Unlike COVID-19, where we didn’t have a vaccine in the early days of the pandemic, here we know how to treat it,” Maniar says. “We have a vaccine to treat Mpox, so it’s really critical we get vaccines to the places where outbreaks are occurring so that we’re able to limit the spread.”

Maniar says people should do what they always do when it comes to mitigating the spread of disease. Wash your hands regularly, be aware of symptoms and go to your health care provider if you suspect you have Mpox or have been in contact with someone who has Mpox.

For people who plan to travel outside the U.S., Maniar says it’s always important to “be aware of the level of risk in the area that you may be traveling to” and, if you have traveled, be on the lookout for symptoms of Mpox.

The symptoms of both the clade I and clade II strains of Mpox are largely similar. It usually starts with a rash but also includes flu-like symptoms and pus-filled blisters. Mpox can last from two to four weeks and, if untreated in severe cases, can progress to bacterial infections, pneumonia and swelling of the brain, even proving fatal.

However, while the clade I strain is more transmissible, it still typically spreads through skin to skin contact and bodily fluids, not airborne transmission. Health care and public health experts know how to contain Mpox, which Maniar says makes a huge difference, as long as people also have access to vaccines and health care services.

That’s not always the case, particularly in countries like the DRC with more strained or less developed public health and health care infrastructure, Maniar says.

Elevating Mpox to a public health emergency, is not the WHO announcing the need for people to panic, Maniar says. Instead, it puts Mpox on the radar for health care workers and “mobilizes global supply chains” to help ensure vaccines are delivered to areas in need. The DRC will receive its first shipment of the Mpox vaccine from the U.S. next week. But with more than 96% of cases in the DRC, according to the WHO, more doses are still needed to address the outbreak.

“There are millions of doses of vaccines that were promised to the African countries that are experiencing the outbreak right now, but there are still gaps in terms of the delivery of those vaccines to the areas that need it the most,” Maniar says.

Maniar says one of the lessons of the COVID-19 pandemic is that investing in global public health and health care infrastructure is good for everybody, not just countries currently being affected by an outbreak.

“What happens in one part of the world will almost invariably impact other parts of the world, so it’s really in our best interest to ensure that we have a global public health and health care system that is really built out as much as possible,” Maniar says. “There are a lot of lessons that we learned from the COVID-19 pandemic, and, unfortunately, the reality is that there will likely be other pandemics in the future. … So, this is really our time to invest in systems and make sure that we’re able to prepare for future pandemics.”