Published on

Sheila Puffer became a top expert on post-Soviet Russia’s free market. Her Northeastern career outlasted it

During her 36-year tenure, the University Distinguished Professor researched corporate strategy and leadership in the emerging capitalist business landscape. Thanks to Putin’s regime, that’s finished. She’s not.

Sheila Puffer’s career has taken her to fascinating corners of the world — the bowels of Russian factories, sand quarries in Australia, Silicon Valley. The place she least expected, though, was wedged into a fitting room with the former first lady of the Soviet Union.

It was 1998, and Puffer, a University Distinguished Professor of international business at Northeastern University, was tapped as the faculty escort for Mikhail Gorbachev and his wife, Raisa, during the university’s commencement festivities in Boston, where the former Soviet president and first lady received honorary doctorates. One afternoon, Raisa wanted to go shopping. Puffer went with her entourage to an Escada store on Boylston Street.

“I went with her, her doctor, her hairdresser and two security agents,” Puffer remembers. “She invited me into the dressing room, and she tried on a pair of jeans that were leopard print, orange and yellow. Very eye-catching. She said, ‘Sheila, do you think Mikhail Sergeyevich will like me in these?’”

What a question. How would the man whose reforms facilitated the fall of communism feel about leopard print denim? With trademark warmth, Puffer rose to meet the moment. “I said, ‘Well of course, you look stunning in those.’”

Raisa bought two pairs: one for Moscow and one for the Gorbachevs’ Sochi vacation home.

It’s a delightful story; Puffer is full of them. But it’s also an apt metaphor for her rigorous, vaunted body of work. She began researching Russian businesses — their corporate structures, leadership, human resource practices and more — in the 1980s, a few years before the fall of the Berlin Wall. For three decades, she had a front row seat to the evolution of Russia’s emergent capitalist economy — a country trying on a new Western identity like a pair of brightly colored jeans.

Puffer co-authored a half-dozen books on business in post-Soviet Russia, visiting the country frequently to conduct ongoing ethnographic research. In that academic field, “she’s number one,” says Dan McCarthy, a legendary retired Northeastern business professor and longtime collaborator. “Sheila is very driven, very focused. She’s finished everything she’s ever started.”

As Russia has slid back into authoritarianism and faced global economic sanctions under Vladimir Putin, however, “there hasn’t been much business going on” to study, Puffer says. So at 70, she’s shifted her focus to corporate sustainability. In particular, she’s studying the emerging “global sand crisis” — a problem with the potential to upend the world’s construction sector.

“In order to [make] cement, the grains of sand have to be angular, and that sand comes from rivers and coastlines,” she explains. “And the sand is being dug up, often by dangerous criminal mafias around the world in Asia, and India and Africa. I’m very interested in it.”

‘I’m not a big dataset person’

Puffer grew up in Canada, the eldest of four children. Her father was a sales manager for a building supplies company, and the family moved numerous times. By the time she left the country, Puffer had lived in eight Canadian cities. “There aren’t too many more,” she laughs.

At 16, rather than move again, Puffer left high school early and enrolled at St. Mary’s University in Halifax. She majored in commerce. “I had to do something practical,” she says. “My dad, I don’t believe he finished high school, so he really didn’t see the value of a university education. He was able to be a successful businessperson without that. So in order to go to university, I had to do something that would end up in a job.”

Soon, however, she was drawn to studying languages and transferred to a university in Ontario for would-be interpreters, with the goal of working at the United Nations. Initially, she considered studying Spanish in addition to French. But the program director thought she was up for more of a challenge and suggested she try Russian. She fell in love with it, graduating with a degree in Slavic studies.

I’m not a big dataset person. I want to keep up with the latest statistical techniques … those are really important and powerful. But we went into companies and interviewed people.

Sheila M. Puffer, Distinguished Northeastern University Professor of International Business

After earning an MBA and a Ph.D. in business, Puffer turned her research attentions to Russia in earnest. In 1988, she and collaborators at Harvard Business School and in Russia spent four months at sites in Russia, Ukraine and the United States interviewing employees at manufacturing companies to investigate how decision-making compared with those they interviewed in the United States. “That was before the fall of the Soviet Union, but Gorbachev was general secretary of the Communist Party and president. And he had been opening up the economy,” Puffer says.

The resulting book, “Behind the Factory Walls,” came out in 1990, offering an intimate peek into a corporate landscape in transition.

Puffer joined Northeastern in 1988. She and McCarthy started working together after she coordinated a Northeastern training program for Russian executives, who came to campus to take classes on different aspects of market-oriented business from members of the business school faculty.

“I gave an introduction to faculty members about Russian culture, what to expect. One of the people in the group was Dan,” she remembers. “He was intrigued, so he approached me and asked if there would be an opportunity for us to collaborate.”

They went to his office, where she noticed a pile of familiar textbooks bearing his name. “I said, ‘Oh, you’re that Daniel McCarthy.’ I had that book when I was doing my MBA in Canada.”

Their academic partnership lasted over 30 years, resulting in over 100 articles and an armful of books. “She was more steeped in traditional academic research and methodology. I was very good at putting ideas together, and [formulating] the right type of article for the right type of journal” says McCarthy, who retired from Northeastern in 2017 at age 85. “We were very different in our styles and skill sets, but we complemented each other.”

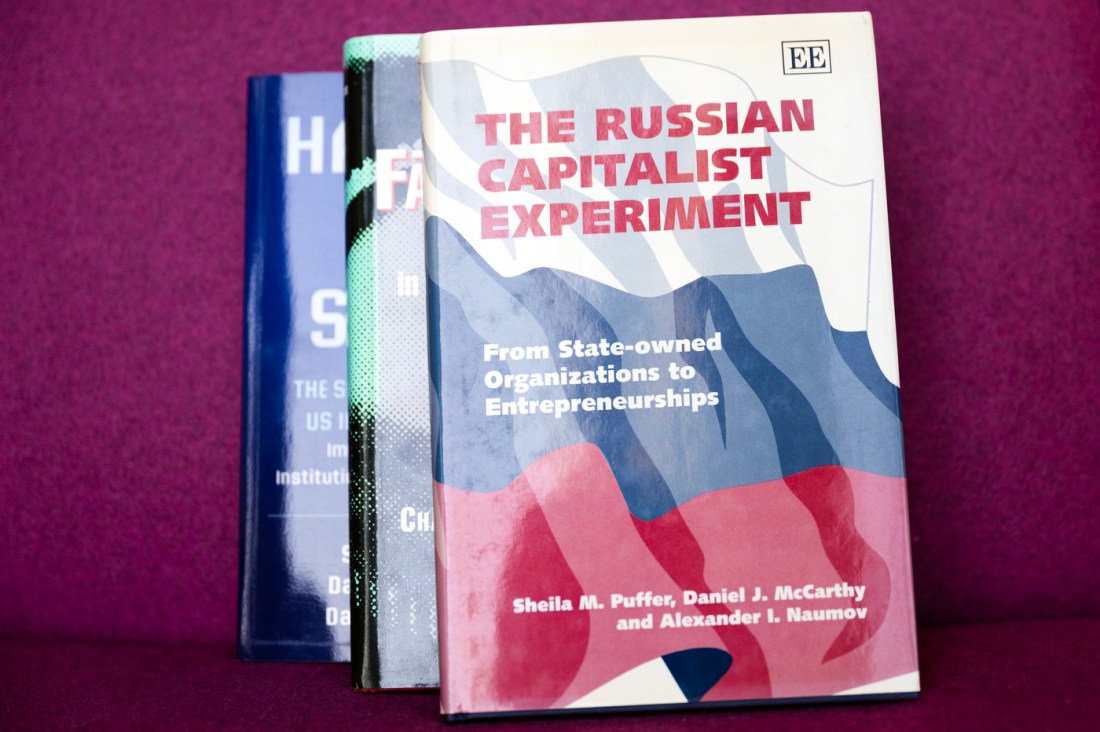

For one project spanning the 1990s under Boris Yeltsin, the pair traveled to Russia every year. Working with a Russian collaborator, they asked business leaders of 10 major companies the same set of questions each visit: “What’s your strategy? What are your human resources issues? How do you approach marketing? Who are your customers?” to name a few.

“We would see the evolution through the eyes of these organizations,” Puffer says. The resulting book, “The Russian Capitalist Experiment,” came out in 2000 and is considered a landmark of Russian business and management studies.

Though business research might seem like cold, calculation-based fare, Puffer’s work, based on ethnographic fieldwork and a steeped interest in Russian culture, starts with human beings at the center of the trends. “I’m not a big dataset person,” she says. “I want to keep up with the latest statistical techniques, large language models and so on. Those are really important and powerful. But we went into companies and interviewed people.”

Shifting sands

As she watched Russia’s economy change, Puffer also watched Northeastern grow into a world-class research powerhouse under President Joseph E. Aoun. The business school was renamed the D’Amore-McKim School of Business in 2012, and Puffer was named a University Distinguished professor in 2011 — the first business school faculty member in Northeastern’s history to receive the distinction.

She’s seen several waves of technological change, as well. In 2000, thanks to a visa snafu, she and McCarthy conducted their annual research interviews via a shaky, primitive video link hooked up by Puffer’s husband. Around the same time, she sat in a faculty workshop in the newly-opened Shillman Hall about how a new innovation was going to change their teaching.

It was “what is the internet? What is a browser?” she remembers. In mid-May 2024, she and a group of professors sat in the very same classroom having the same type of conversation — about the teaching impacts of artificial intelligence. “I raised my hand and said ‘this is déjà vu.’ A few of my colleagues were nodding.”

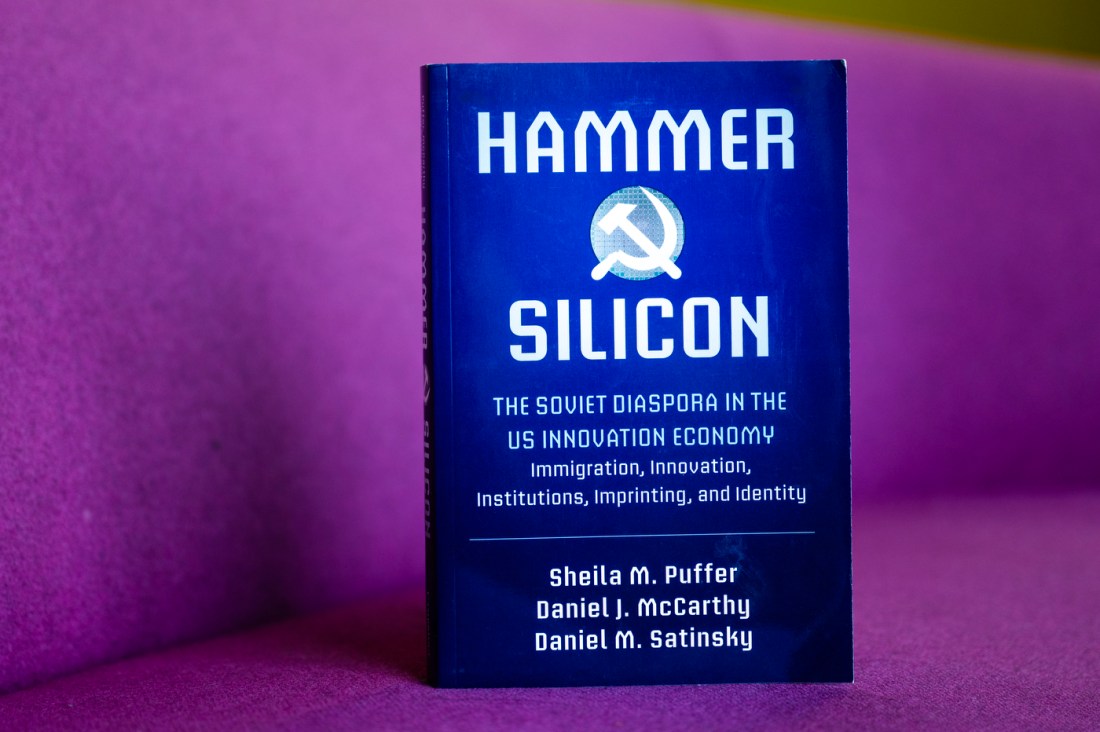

She and McCarthy published their last book on Russia and business in 2018. “Hammer and Silicon: The Soviet Diaspora in the U.S. Innovation Economy” takes a look at the wave of tech professionals who emigrated from Russia to the United States and their contributions in a wide range of fields.

“We interviewed 75 people in Silicon Valley and 75 people in the Boston area who came as immigrants to the United States at different stages over the past 40 years,” Puffer says. “That’s [the book] I’m most proud of.”

They chose the stateside-based project, in part, because Russia’s own free market had all but disappeared. “By 2014, we could see that Putin was starting to reverse course, bringing the state back as the prominent force in the economy,” Puffer says. “He started re-nationalizing key strategic industries, heading in an autocratic direction.”

In recent years, she has shifted her research focus away from Russia — and to mines and coastlines. On a 2016 trip to Australia, she and a group of business faculty went on a tour of a sandstone quarry in the eastern part of the continent. There, she first learned about the global sand crisis. In the years since, she’s co-authored numerous academic articles on the subject, delving into the causes of worldwide shortages of the types of sand used in construction and the feasibility of adopting various proposed substitute materials.

The pivot has allowed her, in this late stage of her career, to work with a fresh batch of collaborators with new areas of expertise — on Northeastern’s global campuses as well as in new (to her) areas of the world, including South America and Asia. With a fresh focus for her considerable energies, Puffer would like to keep working as long as she can.

“I love what I do. It’s the perfect profession for me,” she says. “I love collaborating with people from other disciplines; the teaching is constantly renewing. As long as I’m healthy and capable, I would like to continue.”

Schuyler Velasco is the campus & community editor for Northeastern Global News. Email her at s.velasco@northeastern.edu. Follow her on X/Twitter @Schuyler_V.