A Dublin church built by a saint needs proper recognition for its place in British and Irish history, says expert

Northeastern art historian Niamh Bhalla says St. John Henry Newman’s University Church is “the earliest instance of Byzantinism in ecclesiastical architecture in the British Isles.”

LONDON — John Henry Newman, the influential 19th-century English Anglican convert to Catholicism who was canonized as a saint in 2019, was only in Dublin for four years but left a permanent mark on Ireland’s capital.

Tucked inconspicuously between two townhouses on the edge of St. Stephen’s Green, the city’s central park, sits the University Church that he funded and played a part in designing.

The Church of Our Lady Seat of Wisdom, as it is officially called, has long been seen as an “eccentricity” that Newman conjured up during his short stint as rector of the Catholic University of Ireland, according to Niamh Bhalla, an associate professor in art history at Northeastern University.

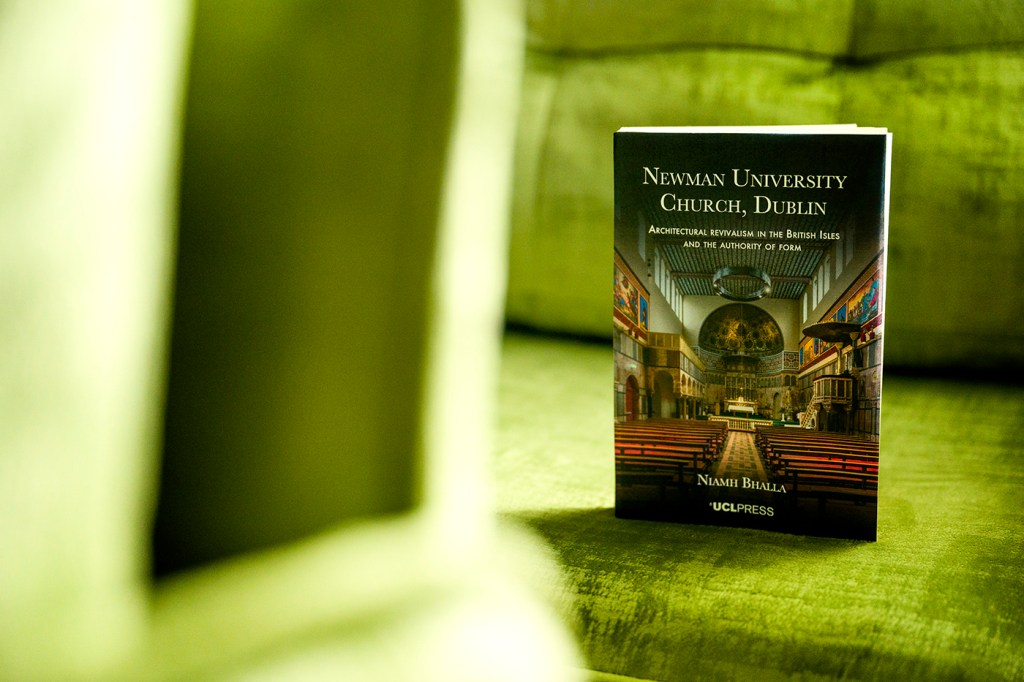

But a new book by the London-based academic, “Newman University Church, Dublin: Architectural revivalism in the British Isles and the authority of form,” argues that it is far from that and should instead be given its dues as an important early stage in the Byzantine revivalist movement in Britain and Ireland, deploying architectural designs used by early Christians living under the Byzantine Empire, which existed between the fourth and 15th centuries.

“It is just not an eccentricity but I think that is how it has been seen,” says Bhalla. “It is very deliberate, it is very careful and it is very much related to the larger intellectual and cultural history of the 19th century. And I think that is the bit as an art historian that I’m very keen to stress, that this isn’t just some whim coming directly out of Newman’s mind.”

The Dubliner argues that the church was intended as a tangible manifestation of the idea behind the university that linked science and religion, while also being a product of the friendship Newman shared with amateur architect John Hungerford Pollen, a fellow convert.

Newman was a prominent figure in Britain in the 1800s, having taught at the University of Oxford and been a priest in the Protestant Church of England. He became interested in Catholic beliefs and rituals and found himself converting to Catholicism in the middle of the century.

In 1854, after Pope Pius IX had thrown his support behind establishing a Catholic university in Ireland — partly in response to so-called “Godless colleges” being set up in cities such as Belfast and Cork — Newman took up the post of rector.

Bhalla’s book, due to be published July 1 by UCL Press, explores how Newman — who would later be made a cardinal and whose series of lectures, collected in the book “The Idea Of A University”, called for a holistic style of education — wanted a church that the university could use for religious services, ceremonies and public preaching.

He was a man on a mission. Newman leased a plot adjacent to the townhouse where the university was based, and work on the church started in 1855. Only a year later, it was hosting its first pontifical high Mass.

Newman decided to finance the construction of the church himself, even though the costs “drastically exceeded estimation” and became a “huge financial burden,” Bhalla found during her reading of his letters from the period. The assistant dean on Northeastern’s London campus says one reason Newman used his own money was because “he wanted to be left alone in terms of what it looked like.”

“And this is where the art historical argument comes in about why he chooses a very different style,” she adds.

The interior of Newman’s University Church, with its replica of a semi-domed Roman mosaic above the sanctuary that was understood to be Byzantine at the time and walls covered in a marble effect made of polished Irish limestone, was not typical of the time in Britain and Ireland, with neo-gothic instead being in vogue.

Bhalla argues in her open access book that the choice behind the design, which she describes as “Romano-Byzantine”, was no accident. Pollen was well traveled and had visited places such as the sixth-century Basilica of San Vitale in the Italian city of Ravenna, St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice and the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul in what is now modern day Turkey, all of which deployed the Byzantine style.

Newman and Pollen had also been to Bavaria — in modern-day Germany — where some of the “earliest Byzantine revival buildings in Europe were happening,” Bhalla says, with the architect seeing the style as a continuation of the ideas of the early church.

Featured Posts

“They are traveling in Europe, they’re talking to people, they’re so connected into the intellectual circles of their day,” says Bhalla. “They’ve been to Bavaria, they’ve seen and admired these other buildings that are happening in this style.

“And so [University Church] is a product of its time essentially, and that is the argument of the book. It is a product of Newman’s mission and vision for this university and his friendship with Pollen.”

It is that “partnership” of Pollen’s ideas of Byzantine architecture representing the early church, along with Newman’s desire to have University Church embody his own analogy of education uniting science and belief, that marries up in the blueprint for the Dublin place of worship, according to Bhalla’s thesis.

“This is the earliest instance of Byzantinism in ecclesiastical architecture in the British Isles,” Bhalla argues.

“Two years earlier there was an apse in a church in London which was kind of Byzantine, but this, I argue, is a very careful, systematic use of a style to deftly and diplomatically declare exactly what it is that this university is all about.

“And I argue that it is about analogy. Newman loves analogy — an analogy with the church of the fourth century, the early church, emerging triumphant over paganism and continuing into the Middle Ages. This is coming after the Enlightenment, when secularism is rising. And that divorce of science and religion is what the university is meant to address — and this church embodies the university.

“So it is a statement about the triumph over paganism. And Pollen uses these words to Newman — there is an awareness here that they are, I think, making a comparison through this style that very much summons up early Christianity and Byzantine basilicas.”

Until now, Bhalla believes University Church has failed to be afforded its rightful place when looking at the history of the Byzantine revival in the British Isles (Ireland was still ruled by Westminster until 1921).

The style would be used when building London’s Catholic Westminster Cathedral, which opened in 1903. St. Barnabas church in Jericho, Oxford, opened in 1869, also used Byzantine features. “When Jericho in Oxford was built, they talked about it as being the first perfect basilica in the British Isles,” Bhalla explains. “There was no real awareness of what they had done across the water.”

Bhalla’s hope is to reverse University Church’s historical anonymity and give this place of worship in one of Europe’s capital cities its due. In fact, as someone who grew up in Dublin and remembers visiting the church, it was only through her academic career and interest in how the Middle Ages have been responded to during history that Bhalla came to understand its significance.

“It was only as time went on, it sort of dawned on me,” she says. “So doing the research has been quite personal and a real personal thing for my family as well, writing this book on this church in the center of Dublin.”

Newman’s university might have failed to make an impact — it would eventually be absorbed into University College Dublin, with which Northeastern has a partnership — but the church he helped establish continues to ignite debate to this day.