Louisiana’s Ten Commandments law ‘intimidating and coercive,’ says legal scholar

Jeremy Paul, professor of law at Northeastern, says he sees the issue — which flies in the face of the Constitution’s establishment clause — making its way to the Supreme Court in due time.

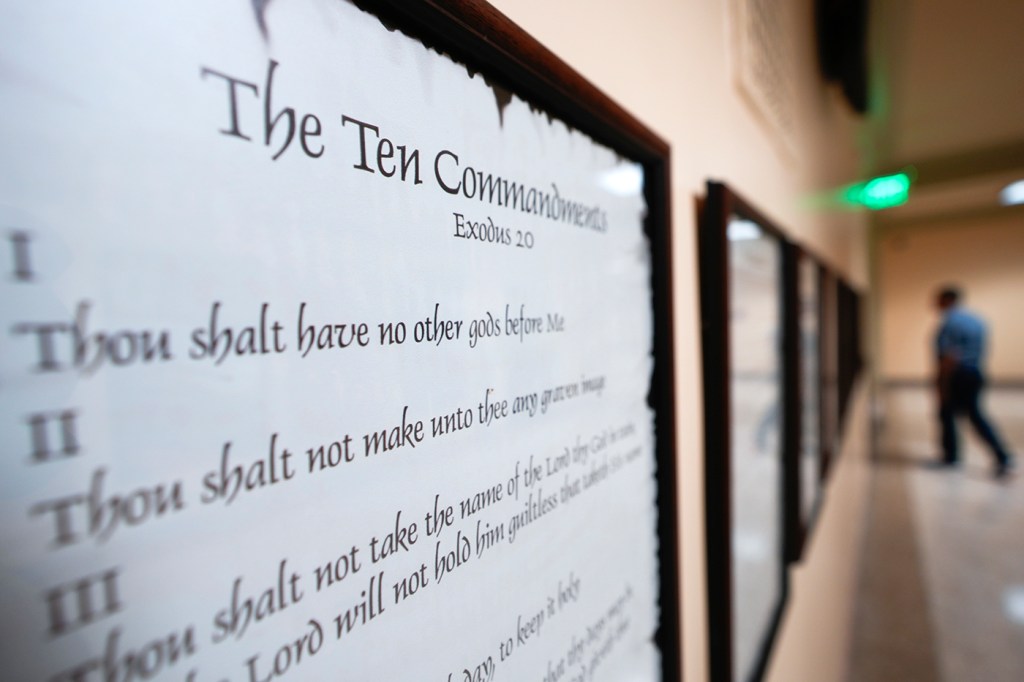

Last week the governor of Louisiana signed a bill into law that mandates the posting of the Ten Commandments in every public school classroom in the state, a move that set off a chain of lawsuits from civil liberties groups.

For Jeremy R. Paul, a professor of law and former dean of the Northeastern University School of Law, the law is more evidence of the growing influence of Christian nationalism, a movement that has long sought to enshrine the values and principles of Christianity into law.

Paul says he sees the issue — which flies in the face of the Constitution’s establishment clause — making its way to the Supreme Court in due time. And, as there have been successful challenges to the longstanding doctrine of the separation of church and state recently (notably, Carson v. Makin), Paul thinks the conservative bench might look to Louisiana’s cause with some sympathy, should the high court decide to review it.

His comments have been edited for brevity and clarity.

What do you make of this latest move by the governor of Louisiana?

I think that one of the challenges the country faces — and I think this is really important, particularly for universities and young people — is the notion that some document written hundreds of years ago ought to be binding on what happens now. If we want to continue our constitutional tradition, it is our responsibility with each successive generation to highlight the virtues of the Constitution and to explain to younger people that while this document has held us in good stead for all of this time, it is — of course — not perfect.

The Constitution established our democracy, and protects free speech, equality, the right to vote, among other things. The Constitution has to be presented to younger people as though it’s consistent with our highest ideals, even when there are ways in which it remains substantially flawed. When you get something like the Ten Commandments, it’s very easy for people who don’t immediately stop to think about the ramifications to just say, ‘What’s the big deal?’ The Ten Commandments are good things — you shouldn’t kill, lie, and so on. But if you actually go and read the Ten Commandments, the first several of them are about which God you’re supposed to pray to and worship. The striking symbolism of putting into secular public schools a particular vision of what God you’re supposed to have — this is completely inconsistent with the whole founding of the country, which is based on the idea that people could come here and worship any way that they wanted.

In a community where 95-plus percent of the people adhere to one of the religions that follow the Ten Commandments (of the Judeo-Christian tradition), if you’re not one of those people, either because you’re avowedly secular or practice another religion, walking into a classroom every day and seeing the official embrace of a religion that you don’t share is intimidating and coercive; therefore, this is a bad thing and we shouldn’t do it.

The ACLU, and others, have sued. Do you think it could end up before the Supreme Court next term?

This will likely go to the Supreme Court, and it will be close. That said, if this had happened 30 or 40 years ago, this would be an open-and-shut case. The ACLU would win, because for years, our federal courts, particularly the Supreme Court, understood there was a sharp line, and that governments couldn’t establish religions. The court then would have seen this as a clear example of the insertion of religion into secular life.

Featured Posts

But it’s not clear that this court would feel the same. There’s a relatively recent case [from 2019] involving a World War I veterans monument in Maryland that includes a giant cross. I mean, it’s huge. It’s a public monument, but clearly it’s a religious symbol. Under earlier law, one would have thought that this wasn’t acceptable. But the court upheld it. And what they effectively said was that the cross, in this context, had transferred over from a religious symbol to a secular symbol. Again, for those Americans of a different faith or no faith, that argument is hard to swallow. The court has been trending more and more in that direction of late: see also the fact that the court now allows money in the form of school vouchers, given from the government to parents, to be used in religious schools.

Why schools and not other public spaces (courthouses, government buildings)?

There are many people in our country who would be more than happy to put the Ten Commandments in every courthouse and legislature. It’s still the case that our legislative sessions open with prayer. These are hard issues.

But the reason why it starts in schools is because schools have to set curricula. The schools select the history books; they select what novels students read. They’re saying, if they’re choosing those things, so what’s the big deal if they want the students to see the Ten Commandments? The answer is the Ten Commandments are undeniably affiliated with religious belief and practices, and the reason for the separation of church and state is not to downplay religion; the reason for the separation of church and state is for everyone to be free to practice the religion that they want.

Do you think Christian nationalism is on the rise in the U.S.?

There can’t be any doubt whatsoever that Christian nationalism is on the rise. The speaker of the House — also from Louisiana — is the most Christian nationalist politician ever to hold that high position. It’s on the rise in the Supreme Court, it’s on the rise in the speakership; it certainly doesn’t reflect a majority of the country, but this is a very divisive move on the part of the legislature and the governor of Louisiana.