Published on

AI is transforming sports for the better, Northeastern baseball legend Carlos Peña says

The Huskies Hall-of-Famer used AI to resolve a nagging riddle of his career, revealing the timeless sport as “a lot less random than we believe it is.”

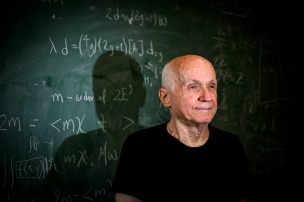

Carlos Peña wanted to understand his own baseball career.

Not that Peña was disappointed. As the highest draft pick to come out of Northeastern University’s baseball program (No. 10 in 1998) he went on to play 14 Major League seasons while earning All-Star status, leading the American League with 39 homers in 2009, and winning Silver Slugger, Gold Glove and Comeback Player of the Year awards.

Peña, who retired in 2014 with 286 career home runs, was inducted into Northeastern’s Hall of Fame.

And yet he had a nagging question. Peña wanted to know why he had struggled so often with elevated fastballs — pitches thrown at the highest speed up around his chest.

Over the years coaches had urged him to alter his tendency to uppercut those pitches. He had tried that. He had tried everything he could think of.

“I would go to the batting cage and work on so many different things,” says Peña, who at age 12 had moved to the U.S. from the Dominican Republic. “I was going to put in the most amount of effort. But what ends up happening is that you feel like you’re throwing darts blindfolded. You just keep going around in circles because of the fact that you really don’t have the right answer.”

The issue stuck with Peña as he bridged to a new career as a studio analyst for MLB Network and other broadcasters. He had a sense that his quest to resolve the high fastball could unlock a deeper understanding of the game he loves.

That answer came to him via artificial intelligence. He turned to Baseball Savant, a cutting-edge MLB database that provides insight into a variety of questions that were unanswerable to previous generations. Peña became a believer in the new approach to sports — and a proponent.

“AI allows me to dive into the nitty-gritty of all the science and break down everything strategically,” Peña says. “I know more now than when I played about why and how things happen.”

The new technologies reveal baseball to be “a lot less random than we believe it is,” he says.

The hidden variables

“All of the professional sports I can think of are taking data very seriously,” says Usama Fayyad, inaugural executive director of The Institute for Experiential AI at Northeastern. “It has become a necessary and strategic tool.”

Baseball, whose history is written in numbers, gravitated naturally to advanced analytics. That data revolution was well underway while Peña was hitting .324 with 24 homers and 93 RBI in his two Northeastern seasons (1997-98).

“In the late ’80s and early ’90s, the sports industry in the U.S. was ahead of everybody else because the U.S. sports scene has always been dominated by statistics and analytics — more than any other country,” Fayyad says. “They identified data as a big asset and started saying, instead of just doing analytics on a game and statistics on a player’s performance, what if we can start using the data to build predictive models on players, game strategies and likely scoring of different defensive or offensive configurations?”

The data-driven approach enabled plays to be broken down and analyzed in new ways, creating appreciation for players whose contributions had previously gone unnoticed.

“Some of the earliest cases were in basketball where people quickly realized the analytics can give us an edge here,” Fayyad says. “What should the team composition be? How should we respond to substitutions by the opponent? What do we do against a certain kind of defense?”

These questions were being asked as AI was emerging to help high-level pro teams across a range of sports track and manage data on every action by every player during every game.

“Sometimes it’s a hidden variable you never knew about,” Fayyad says. “You see the person who scores a touchdown or a basket — but you’ve ignored the player who did something to make it possible. So a lot of that started getting analyzed.”

Today AI is influencing virtually all aspects of sports at the elite level. It is used to analyze the posture and technique of players while also helping team executives in their analysis of potential talent and coaches in their development of the most efficient lineups and game plans.

Biomechanical markers worn by golfers identify the best way to swing the club. Video Assistant Referee (VAR) technology helps officiate controversial offside violations at soccer matches around the world.

I would go to the batting cage and work on so many different things. I was going to put in the most amount of effort. But what ends up happening is that you feel like you’re throwing darts blindfolded. You just keep going around in circles because of the fact that you really don’t have the right answer.

Carlos Peña

Off-the-field applications include reliance on AI for the complicated task of organizing team schedules for each season. NFL franchises access analytics to grasp dissatisfaction from fans about the game presentation and other aspects of their experience in the stadium — enabling employees to react while there is still time to make it right.

The AI sports revolution is still in its early days, says Fayyad, who notes that teams are just beginning to grasp how to forecast and prevent injuries.

Eventually, says Kwong Chan, executive director of the DATA Initiative at Northeastern, a more sophisticated understanding of the qualities of success may help steer young people into sports they never would have considered playing.

“Should this person even be a baseball player?” Chan says of a 15-year-old miscast prospect who could be directed by AI analysis. “Maybe he could go to India and be a cricket player instead.”

“There are two separate strategy areas,” Chan adds. “One is using these methods to do what you’re doing already, but do it better. And then the second category is doing things that no one else has thought about.”

‘It’s about how you use it’

A quarter-century since Peña starred for the Huskies, assistant coach Chris Bosco is charged with tracking data for Northeastern’s baseball team. The metrics have influenced all kinds of decisions made by coach Mike Glavine, who has steered Northeastern to the NCAA tournament two of the past four seasons.

“TruMedia is the same thing they use in the Major Leagues,” Bosco says of the online portal that is deployed by every major NCAA baseball program. “We use it every day.”

The data-rich breakdowns have enabled the Huskies to analyze opposing defenses, including tendencies by pitchers in specific situations as well as the weaknesses and strengths of each hitter.

“The biggest use of it is for opposing scouting reports,” Bosco says. “And then we also use it to self-scout.”

The Huskies have focused on condensing the data so that players won’t be overwhelmed by too much information.

“One thing we’re always talking about is, ‘The guys don’t need to see this,’” Bosco says. “It’s good for us [as coaches] to look at, but for the players we need to simplify it. For instance, I coach the base runners, and before the game I’ll say, ‘Hey, they pick off [runners] with two strikes all the time — so be ready for that.’

“Getting this information is so cool. You can see anything you want to see. But it’s about how you use it.”

The sporting applications of AI are endless. Huaizu Jiang, a Northeastern assistant professor of computer science, is developing an AI slow-motion model for sports that fills in the blanks of existing real-time videos, creating intermediate frames that enable super-slow replays of athletes to be viewed seamlessly without the typical graininess or choppiness.

The technology may make sports more entertaining for viewers, Jiang says. He also believes athletes can benefit from an enhanced breakdown of their form while swinging a tennis racket or baseball bat.

“I realized this potential when I was taking my daughter to her first golf lesson,” Jiang says. “She had no idea how to swing or what a good position should be. I thought if I could show her her swing in slow-motion mode, that would be very helpful for her.”

All of these advancements leave Peña realizing how he might have benefited during his playing career. At the same time, he adds, it may not be too late for him to jump into the AI game.

Identifying the key features

Once he had learned how to put the complex data to use, the answer to Peña’s enduring question turned out to be simple.

“I needed to swing a half-second earlier,” he says.

It turned out that he had been upper-cutting the high pitches in an attempt to create space. To make up for being late on the pitch, he had been leaning back. But neither he nor anyone else had been able to recognize the flaw in his approach.

“AI is able to use computer video to detect so many nuances that the naked eye would miss,” Peña says. “Start half-a-second earlier and now the uppercut disappears. The breakdown in mechanics doesn’t happen. You don’t spend two hours in the cage trying to change your swing.”

Fayyad understands how MLB Statcast — an AI tool available at Baseball Savant that monitors and assesses player movements, pitch velocity, launch angles and more — was able to resolve Peña’s issue.

“The algorithms quickly identify the key features,” Fayyad says. “The analogy I would draw is with facial recognition, where the whole idea was to recognize people from mug shots.

“What is amazing is how the algorithms very quickly homed in on certain attributes that are resistant to things like disguise or change. So a typical face recognition algorithm now takes six or seven values — the distance between the eyes, where the nose tip is, the distance between the nose and mouth, some attributes of the mouth — and that’s all it needs to pretty much nail a face recognition.”

A similar dynamic of defining the measurables that matter produced an answer to Peña’s career-long mystery.

Peña’s analysis on TV is driven in no small part by data. This new approach to the timeless sport has also helped him recognize his potential. Peña is now studying AI with the dream of working in an MLB front office and ultimately running a franchise’s baseball operations.

He believes the next generation of leaders in baseball must straddle both worlds. Peña knows what it’s like to compete on the field. And he embraces AI and every other cutting-edge asset that can help elevate the level of competition.

“With AI you have a very, very, very sharp sword,” he says. “But it all depends on your fighting style — how you wield it.”

With AI, he says, you have to know what questions to ask in order to get the right answers.

By looking into his past, Carlos Peña discovered his future.

Ian Thomsen is a Northeastern Global News features writer. Email him at i.thomsen@northeastern.edu. Follow him on X/Twitter @IanatNU.