Proposed legislation could protect access to IVF in wake of attacks on reproductive rights, Northeastern law expert says

The Right to IVF Act would ensure patients have access to the fertility treatment and ensure coverage, a move one Northeastern expert calls “an important step.”

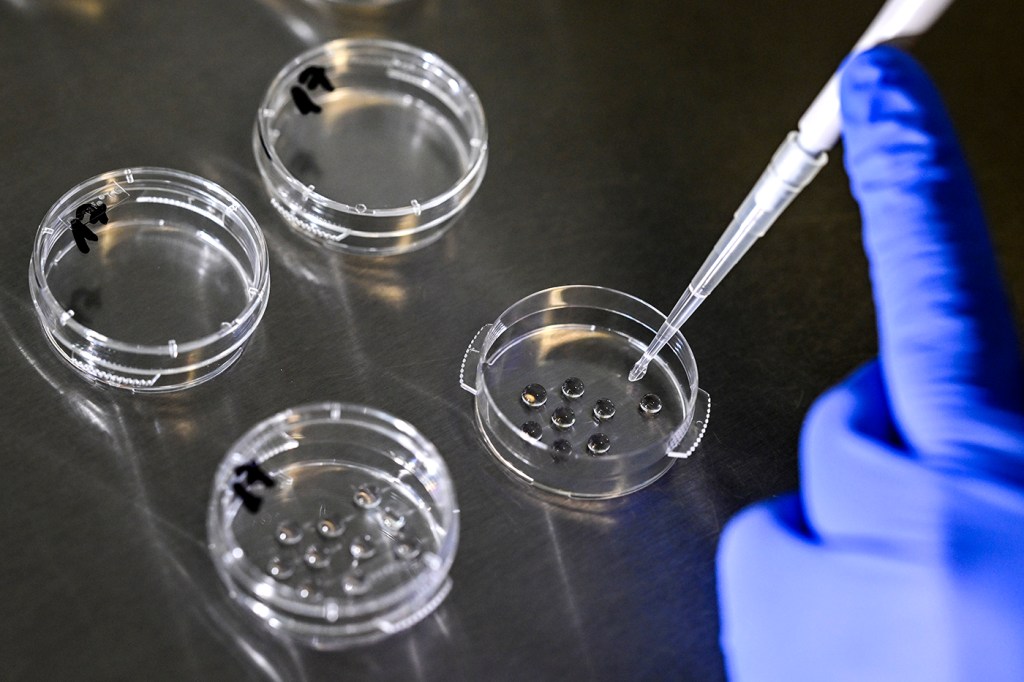

About 2% — tens of thousands — of babies born in the United States each year are conceived using in-vitro fertilization, a fertility treatment that’s been considered a “great triumph of modern medicine.”

But the legal viability of this procedure was called into question this year after the Alabama Supreme Court ruled that frozen embryos could be considered children. The ruling only applied to negligence cases concerning embryo destruction, and Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey later signed a bill to protect providers and patients.

However, concerns remain about the protection of the treatment, especially with 13 states considering legislation defining personhood, measures that could affect the legality of IVF.

The Supreme Court also overruled Roe v. Wade two years ago this month in the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization case, saying the Constitution does not confer the right to abortion. The overruling of Roe v. Wade emboldened some politicians to go after reproductive rights, said Katherine Kraschel, an assistant professor of law and health sciences at Northeastern University who is an expert on health policy and reproduction.

“What happened in Alabama has really gained momentum,” Kraschel added. “It’s in response to the Alabama decision that there are Democratic members of Congress that are gravely concerned (and want to) protect the patients’ ability to continue to access the important health care that they need in order to build their families.”

A group of Democratic senators recently introduced a quartet of bills that Kraschel says could help protect access to the fertility treatment.

The Right to IVF Act would protect IVF providers, (much like the Alabama bill), ensure patients have access to the procedure, and assure more insurance providers cover this type of care. The bills would also safeguard access to IVF for members of the military and veterans.

Kraschel said the bills are carefully written to avoid overstepping state laws regarding embryo destruction, while still protecting providers and patients, and patients’ access to the procedure.

“It stands to create a floor for what states can do regarding restricting IVF,” she added. “That just drives home the fact that really what they’re concerned about is people’s access to their health care and their reproduction and right to build their families however they want.

“It will do a lot to protect IVF and people’s ability to access their health care and especially keep states from interfering with their ability to safely access fertility care and to store their embryos. … The core goal here is to protect patients who need fertility care from interference between them and their provider.”

In protecting this right, Kraschel said the bills succeed where other reproductive justice acts have fallen short.

“Historically, the way that advocacy has evolved has been to shore up a right without sufficient concern for the ability to access that right,” Kraschel said. “Part of what’s going (with this bill) is a recognition they could protect this right and that’s what they aim to do in response to the Alabama decision.”

Kraschel said many insurance policies already cover fertility care, but most don’t provide robust coverage. This type of bill could aid many, she said, especially single people and people in the LGBTQ+ community who want to use IVF to expand their family but don’t have an infertility diagnosis that is sometimes required to trigger coverage.

Increasing coverage can also improve accessibility by easing the costs of IVF that Kraschel said is “prohibitively expensive.”

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the average cost for a cycle of IVF is between $15,000 and $20,000. Patients usually get pregnant after 2.5 cycles, meaning the costs can run over $40,000.

The DHHS also reports that most states do not require private insurance to cover any fertility services and Medicaid coverage is optional. Some insurance policies will cover diagnosis and treatment, but the cost of the appointments and procedures for a diagnosis plus the medications needed for IVF can pose an additional cost to patients.

“(This) is going to make it more equitable,” Kraschel said. “It will not only shore up protecting patients who already have access to care, but stands to also improve access.”

Featured Posts

However, these bills will not become law until passed by Congress, something Kraschel said is unlikely to happen given the divide over reproductive rights.

Sen. Tammy Duckworth of Illinois, who led the Right to IVF Act along with fellow Democratic Sens. Patty Murray of Washington and Corey Booker of New Jersey, sought to pass part of the bill, but was blocked by Republican Sen. Cindy Hyde Smith of Mississippi, who said that no state had banned IVF.

Republican Sens. Ted Cruz of Texas and Katie Britt of Alabama introduced their own act to protect IVF that would cause states to lose Medicaid funding if they ban access. Democrats said this bill didn’t do enough to prohibit restricting the procedure.

Kraschel said that while IVF might not be banned, there’s legislation lawmakers can put in place to make the procedure nearly impossible to pursue, such as allowing the creation of only one embryo at a time, which drastically reduces the odds of a successful pregnancy and increases the cost of the procedure.

“(The Right to IVF Act) is one tool that is needed right now — along with action by other states — to protect IVF,” Kraschel said. “I don’t think we’re going to have one silver bullet bill that’s going to shore up and protect these reproductive rights. But it’s certainly an important step, and one important tool to have in the toolbox moving forward.”