Published on

Your podcast needs a theme song. Good Dog Licensing can help

This student-run Northeastern organization connects musicians with creatives looking to set projects to music. Law students draw up the agreements — an arrangement that gives everyone valuable, real-world experience.

For the final project in their True Crime Media class at Northeastern University this past spring, professor Laurel Ahnert’s students created a podcast, “Under Suspicion.” Each team of three or four was responsible for one episode of the multi-part series, delving into issues ranging from the role of TV audiences in solving real-world cases to the flourishing economics of the “true crime” industry.

Like any good podcast, it needed a good theme song. What’s “Serial,” after all, without those opening bars of tinny piano, or “The Daily” without its jazzy yet ponderous electronic score?

For the True Crime project, “I wanted something super creepy and like low sounding — a lot of bass,” says Carolyn Alexander, a student in the class.

Ahnert turned to Good Dog Licensing, an on-campus outfit that connects student creators with music for films, podcasts, video games and other artistic projects. At the beginning of the semester, the media studies professor sent a project brief to Russell Zingler, a 2024 music and psychology graduate who completed his final co-op at Good Dog.

Zingler provided the class with five potential songs; by popular vote, they selected “Aiden, My Sweet Aiden,” an electronic instrumental track by the artist Burial Grid. Combining droning synthesizer with atonal strings, the song is foreboding and futuristic-sounding “horror synth”— appropriate for a project about the ways people consume and process unspeakable acts through their screens.

“Having that music in the background makes it sound more professional,” Alexander says. “Before making this, I didn’t realize how much went into the audio editing.”

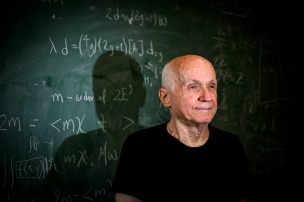

Budding creatives in the internet age have access to plenty of resources for finding open-source tunes for projects, from YouTube’s sound library to Creative Commons and podcast software add-ons, like Descript. But Good Dog, launched in 2021, offers the Northeastern community more than sound files. Headed up by David Herlihy, a Northeastern music professor who runs a private entertainment law practice and moonlights as a successful rock musician, the organization is also a three-pronged experiential teaching tool.

Creatives working in media that call for music get valuable practice — in choosing the perfect sounds for their projects, and in articulating their needs in writing. Musicians get low-stakes exposure to legal contracts.

“If you graduate and become a filmmaker, you’re going to need to know how to speak to music supervisors.” Herlihy says. “This is a fundamental skill set.”

Additionally, future attorneys hoping for a career in entertainment law get training in key aspects of that popular field — a small group of Northeastern University School of Law students draft the contracts for the organization.

“Any clinical work students can do during law school, whether it’s transactional or litigation based, is incredibly helpful because they’re advocating on behalf of real clients,” says Alexandra Roberts, a Northeastern law professor dually appointed to the university’s music department.

For a highly competitive specialty like entertainment law, that practice can be especially valuable. “It helps them build confidence and client-facing skills,” Roberts says. “All of that signals to employers that these students will hit the ground running.”

For all three groups, the service lays the groundwork for navigating the complicated, ever-shifting landscape of music rights — one growing only more muddled for all involved in the age of streaming and artificial intelligence.

“Licensing is at the core of everything,” Herlihy says. “Every new venture, every use of photographs or recordings or songs. Good Dog is, I believe, the first bona fide music licensing service within the context of a university.”

Editor’s Picks

The rights stuff

Unless it’s in the public domain, like “Happy Birthday” or Beethoven’s symphonies, all recorded music has a copyright — if you want to use a song as the theme for your TV show, you have to get permission or pay royalties to use it. Popular songs are tougher to obtain; “Yellow Submarine” will cost many orders of magnitude more than an electronica track from an indie artist in Western Massachusetts.

Zingler, who handles the music requests for Good Dog, says even those basics are news to many who submit briefs to the service. “I’ve had students come to me saying they want to license a Marvin Gaye song,” he says, shaking his head. “Well, you have to have a lot of money to do that.”

Others will simply rip audio from YouTube, unwittingly committing copyright infringement. Zingler, who wants to work in the music industry in New York after graduation, helps them find what they want — legally, and in this case, for free.

“Music is often an afterthought,” Zingler says. “This is the first time that a lot of these student media makers and musicians are experiencing the process of licensing media, so this introduction of how it works and the bandwidth of what they can do is really informative.”

It also teaches the creators to articulate what they want, conveying the content of their project and the emotions they’re aiming to evoke in a musical language.

“You’re not going to get Marvin Gaye,” Herlihy says. “But what about Marvin Gaye would serve your project? It’s a real skill for both filmmakers and for music supervisors to be able to translate the intended impact into music that’s going to do the job.”

To find that music, Zingler draws from artists signed to Green Line Records, Northeastern’s in-house music label, and seeks out tracks on platforms like SoundCloud and Bandcamp. Requests run the gamut: for a recent student film, the director asked him for tracks that were “acoustic and gentle … something that makes whoever is watching it feel a bit solemn yet hopeful.” Another brief, from a video game designer, called for “electronic, spacey, ambient, futuristic but also nostalgic” music for a game demo.

On Bandcamp, “you can sort very specifically by genre,” Zingler says — “Aiden, My Sweet Aiden,” for example, has tags including “ambient industrial,” and “hauntology” — “and we try to keep it [to artists] under a certain number of monthly listeners to increase the likelihood of them actually responding to us. We also make sure they’re not signed with another label so it’s easier to negotiate directly with them.”

Artists don’t make any money — in all likelihood, the student projects for which their music is intended won’t generate any. But Good Dog contracts don’t preclude them from the possibility.

“If a filmmaker does end up selling their project, the musician can get performance royalties down the road,” says Gabriella Epley, a 2024 law school graduate who works with the organization. “It’s never our goal for anybody to be left financially uncompensated for their work.”

Terms of use

Epley began working with Herlihy in 2023 as part of an independent study on music licensing. That summer, she and a small group of fellow law students held weekly sessions drafting various contract templates for the service, including a Creative Commons-like permissions structure. Not all of them were adopted — the bulk of Good Dog’s contract work now deals with the one-on-one arrangements between musicians and artists — but Epley says working them up has still been invaluable. One of her recent projects was developing a “Terms of Use” contract for the Good Dog website, to formalize the use of samples from its growing media library.

“It’s been really good practice for me, even if they don’t turn into something that’s ultimately used,” she says.

That kind of direct experience can be hard to come by for entertainment law, a generalist field with a not-so-obvious career path for those looking to practice it.

“It can be really challenging,” Roberts says. “Some will tell you to go to the biggest, most prestigious firm you can and get more general training, then try to branch out. Others will [recommend] a summer or a co-op or an internship at a record label or a museum — whatever it is that you’re hoping to focus on — then to get a job and climb through the ranks there.”

Another obstacle is that law school classes writ large tend to focus on litigation and trial cases, she says. But the bulk of entertainment law practice is transactional in nature.

“Many lawyers never litigate at all. They might be registering copyrights and trademarks or managing an IP portfolio. Music lawyers in particular might be clearing samples, negotiating with record labels, assisting with endorsement deals, things like that,” Roberts notes. “So actually doing that type of work and getting exposed to those documents is really valuable.”

If you graduate and become a filmmaker, you’re going to need to know how to speak to music supervisors. This is a fundamental skill set.

David Herlihy, Northeastern University music professor and Good Dog Licensing faculty advisor

Whatever the students’ aspirations — as musicians and artists, or industry professionals like music supervisors and lawyers — the low-stakes interactions Good Dog facilitates offer a solid foundation in the shifting sands of the music landscape. AI, in particular, has introduced a host of existential questions for the industry.

“One concern is what happens when generative AI trains on the body of work of a particular musician,” Roberts says. “What if it can produce songs that sound exactly like Drake? Or you can say ‘do this song in the style of Taylor Swift,’ and people will hear it and believe it’s her?”

“There’s a lot of discussion right now about what’s actually protectable,” she continues. “Is the sound of someone’s voice protectable? Is the general style of the music that they make?”

Herlihy worries that as machine learning becomes more sophisticated, media companies might find ways to take humans out of the music direction process entirely. In the future, a director might be able to tell a computer, “give me a pastoral orchestral arrangement that echoes Mozart for this drone shot over an Irish landscape,” and have it spit out a score, he says.

But he hopes well-versed, experienced players in the industry — the type of people Good Dog is trying to nurture — will be able to use AI as a tool to enhance the artistic process, rather than replace it.

“I would say Good Dog is a hedge against AI.”

Schuyler Velasco is the campus & community editor for Northeastern Global News. Email her at s.velasco@northeastern.edu. Follow her on X/Twitter @Schuyler_V.