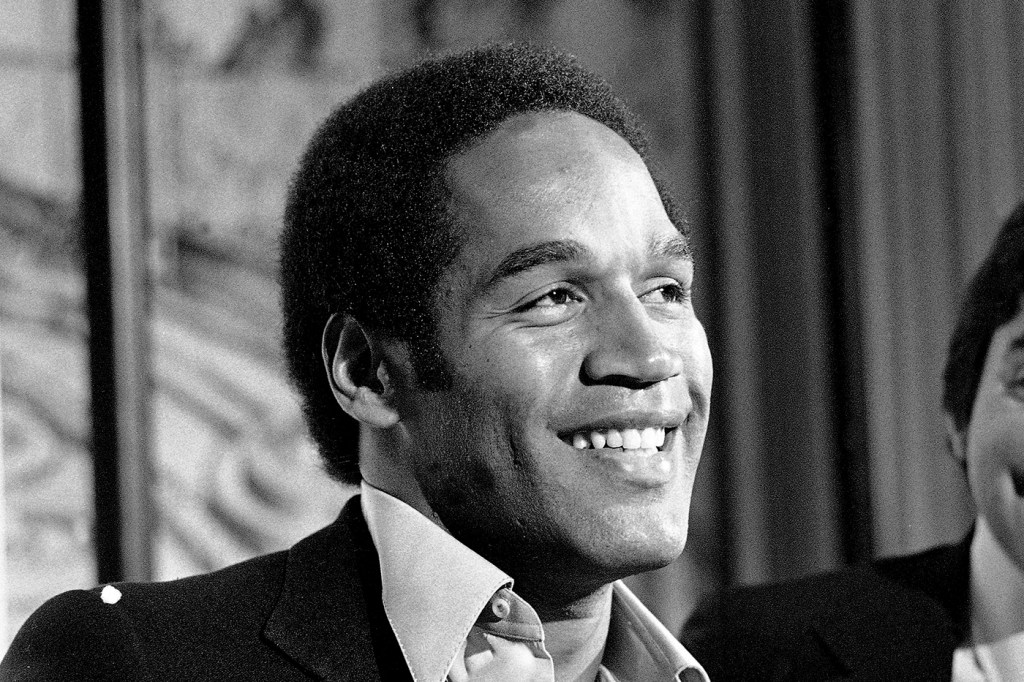

O.J. Simpson is dead. How the former NFL star’s double-murder trial captured the nation’s attention

A Northeastern expert says the trial “marked a significant moment in American culture, pop culture, representations of the justice system and the operation of the criminal justice system itself.”

O.J. Simpson, a star college and NFL running back, actor and public figure who was acquitted in a 1995 double-murder trial that gripped the world, died on April 11. His family said Simpson succumbed to prostate cancer.

But the impact of that highly controversial trial — dubbed “the trial of the century” — on the American public, pop culture and Simpson’s own celebrity at that time can hardly be overstated.

While a significant cultural phenomenon, the trial also seemed a reflection of broader societal issues in the 1990s, says Laurel Ahnert, an assistant teaching professor of media and screen studies at Northeastern.

As one of the first televised trials coming on the heels of the Rodney King trial, the verdict underscored racial divisions; heralded the rise of the 24-7 news cycle; and permanently shaped TV culture and the “legal drama” genre.

“I think what the trial really did was to crystallize some key issues that were going on in the 1990s that then became sort of common sense going forward,” she says. “It crystallized bringing cameras into the courtroom, for example, which was a huge debate at the time among the Supreme Court and the public.”

Ahnert says the “trial itself marked a significant moment in American culture, pop culture, representations of the justice system and the operation of the criminal justice system itself — and I think that’s all worth reflecting on.”

“The case clarified the distinction between reasonable doubt and actual innocence in the popular imagination — how the burden is on the prosecution to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt and the defense wins if it can prevent the government from carrying that burden rather than proving the government is wrong,” says Daniel Medwed, Northeastern distinguished professor of law and criminal justice.

As to the presence of cameras in the courtroom, Medwed says the “legal system hasn’t quite resolved whether that’s a good thing or a bad thing.” Case in point, federal courts still bar cameras in open court.

‘A monocultural event’

Charged in 1994 with the killings of his ex-wife Nicole Brown Simpson and her friend Ron Goldman, Simpson was acquitted in what has been described as the most infamous verdict in modern history. Three years later, a jury found him liable for the deaths in a civil case that awarded $33.5 million to the victims’ families.

In 2008, Simpson was again tried in court — this time for an armed robbery and kidnapping stemming from a 2007 incident in which he and other men invaded a Las Vegas hotel and stole sports memorabilia, including some of his own, at gunpoint. He was convicted and sentenced to 33 years in prison with the possibility of parole. In 2017, he was released from prison.

Featured Posts

For Steve Granelli, associate professor of communication studies at Northeastern University, the trial conjures the concept of “monoculture,” or the idea that an event “everyone had to reckon with in real time.”

“It was exactly one of those monocultural events,” he says. “No matter what else you were consuming at the time … you were going to be exposed to it. If nothing else, it gave people a touchstone to remember exactly where they were in time.”

Granelli says “you could make the argument that, by the mid-90s, [Simpson] was the most famous person” in America.

But he also argues that the trial “set a very dangerous precedent for the power and impact of eyes, attention and fame” in general.

“There was a feeling of a miscarriage of justice by a large segment of the population, and also a deep reflection about the role that the media and celebrity may have played in Simpson getting away with this,” he says. “The lasting impact is not one that the trial changed our breathless appetite for celebrity, scandal, gossip or courtroom drama — I don’t think any of that went away — but rather it is that self-reflexive moment afterwards that caused us to pause.”

The rise of TV courtroom drama

Ahnert, whose research has focused on the ethical questions posed by documentaries, also notes that the benchmark trial may have helped fuel a boom in the legal drama TV genre. Criminal trials, she says, possess a “neat narrative arc,” and often tap into the darker side of human nature.

“One of the things that communications scholars have talked about in relation to the televised trial is the way in which a trial and, say, a documentary share a similar structure, which is a three-part structure: the prosecution, the defense and the closing argument,” Ahnert says.

She continues: “Other folks have pointed to the ways in which there’s a melodrama to a trial, right? There’s a villain and a victim. Of course, it’s about the evidence; but there are a lot of emotional arguments that are made.”

“It was such a high-profile case that I think the consensus was that it was so abnormal,” Ahnert says. “And yet it highlighted some key problems in the criminal justice systems, and we see these problems being articulated more and more in docuseries and documentaries throughout the ’90s — and with films like ‘Paradise Lost’ — which is this creeping lack of faith in the criminal justice system.”

And there is also the performative aspect of the courtroom drama, as when an attorney makes a masterful closing argument. Johnnie Cochran, one of Simpson’s attorneys, became an instant celebrity for the array of rhetorical skills he put on display during the trial, Granelli says.

“People all of a sudden were much more aware of oratory,” he says.

Medwed says the trial solidified the notion of “differential justice” — “that the wealthy and powerful, by virtue of their bank account, get a higher level of legal representation than those who lack those resources.“