Published on

What is it like to argue a case before the Supreme Court?

Two veteran Northeastern litigators who have argued before the Supreme Court on numerous occasions, Michael Meltsner and Martha F. Davis, reflect on their decades of experience, and how the court has evolved.

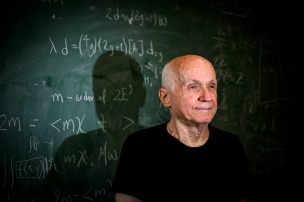

Former Northeastern law professor Michael Meltsner, who has argued six cases before the U.S. Supreme Court, remembers what the late Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg once told him about such occasions.

“Ruth said to me: you have a captive audience,” he says.

What is it really like to argue a case before the U.S. Supreme Court, and how is it different for litigants today than in years past? Two Northeastern lawyers have plenty of experience to draw upon. Meltsner, who is Northeastern’s George J. and Kathleen Waters Matthews Distinguished University Professor of Law Emeritus, has argued six cases at the Supreme Court’s lectern — mostly in the 1970s. Martha F. Davis, university distinguished professor of law, argued one case, and second-chaired six others throughout the 1990s and 2000s.

An experience unlike any other

“When you stand up before the court for the first time, you realize something important,” Meltsner tells Northeastern Global News. “That is that you know the case better than anyone in the world.”

The cases Meltsner and Davis argued ran the legal gamut. Davis argued an equal protection challenge to a sex-specific federal immigration statute (Tuan Anh Nguyen v. Immigration and Naturalization Service); Meltsner’s first Supreme Court case — which he argued at just 26 — examined whether the Sixth and 14th Amendments rights of an Alabama man, who was Black, convicted of assault with intent to murder were violated during the legal processes that played out following his arrests (Coleman v. Alabama).

When you stand up before the court for the first time, you realize something important. That is that you know the case better than anyone in the world.

Michael Meltsner, George J. and Kathleen Waters Matthews Distinguished University Professor Emeritus at Northeastern

The pair offered glimpses into what preparing for oral arguments looks like, and how presenting a case in front of the Supreme Court can be an experience unlike anything else. For attorneys who’ve never tried a case in the nation’s highest court, the procedural twists can throw even the most practiced lawyers, they say.

“One thing that you have to learn as a Supreme Court litigator is that it really doesn’t matter much what the lower courts have decided,” Davis says. “You’re really arguing from first principles, and sometimes it’s hard for litigators to make that leap.”

Having been part of numerous cases during the Rehnquist Court era, Davis was privy to the behind-the-scenes strategizing that legal teams engage in to maximize their chances of success. Those strategies include deciding how to divide the allotted time for oral argument among those staffed on the case.

“I think one of the things I was surprised to learn — and in retrospect, it makes sense — is that there is a lot of jockeying about who gets to do arguments, because everyone wants to,” Davis says.

Meltsner, who argued Coleman v. Alabama to a successful conclusion (the man’s conviction was vacated), says Supreme Court newcomers should consult a compilation of courtroom recordings collected in a work titled “May It Please the Court.”

Of course, by the time they appear before the court, Supreme Court litigants will have undergone a certain amount of mooting to sharpen their oratorical skills, he says.

“Any lawyer who has a significant case before the court, or who wants to do an excellent job, is going to have what we used to call a dry run, or a practice argument,” Meltsner says. “Often, you are beaten up with questions, and that’s a great way to prepare. I did that with almost every argument I ever had.”

Oral argument: It’s an art, not a science

Davis recalls that in Tuan Anh Nguyen v. Immigration and Naturalization Service — the case she argued in 2001 dealing with the question of whether an immigration statute concerning children born of wedlock violated the equal protection clause — there was noticeable tension on the bench.

Davis says it was the first equal protection case the high court reviewed since the highly divisive Bush v. Gore ruling months prior, which handed George W. Bush the presidency in a controversial decision barring a recount of Florida votes in the 2000 presidential election.

“There’s a dynamic between the justices that sometimes you have to ride with,” she says.

If you’re the lead oralist in the case, how do you know if it’s going well?

“This is another thing you learn if you’re a repeat player: it’s only going well if you are in dialogue with the justices who you think are against you,” Davis says.

Oral arguments give litigants an opportunity to speak directly to the justices in what often amounts to an hours-long, unpredictable and sometimes digressive series of questions, comments and colloquies. One age-old question about oral argument is whether it actually affects the court’s decisions in the end, or if it’s mostly performance art — a way to score rhetorical points with the justices, and avoid any embarrassing argumentative slips or mishaps.

“It’s always been somewhat unclear how important oral argument before the court really is,” Meltsner says. “The justices certainly want it to appear so, because it’s their only public appearance as a group, and lawyers who practice before the court also want [oral arguments] to seem important because that’s the way they earn prestige and gain reputation.”

The oral argument tends to be more an art form than an exact science in the final analysis, Meltsner says. A little bit of jousting here and there is part of the performance.

Exchanges during oral arguments often contain clues

But far from just sophistry, the exchanges that occur during oral arguments often contain clues as to how the justices are positioned on the issues in the case. That is even more so the case today as, Meltsner notes, the court is surrounded by and subsumed in publicity.

“They often signal positions that end up being the positions they take in decisions, and it’s as if they are also communicating to a larger audience,” he says.

Meltsner says the court today is fully aware of the public’s gaze — its preferences on certain hot button issues before the court, and the activism accompanying them — which has become even more penetrating alongside the development of the Supreme Court beat and the growth of legal journalism more broadly. Court reporters, such as The New York Times’ Linda Greenhouse, wielded such influence as to have a real impact, some argue, on the justices’ behavior during oral arguments.

As a result of a mix of factors, including the external pressures exerted on the bench, oral argument has taken on “more of a political dimension” — a fact that broadly reflects divisions in U.S. society at-large that have come to a head in the very process of picking Supreme Court justices for job, Meltsner says.

“But the real purpose of oral argument was to reach a decision; to decide a case; to test arguments,” he says. “That still goes on, but it’s somewhat more in the shadows than it once was.”

The number of upstart lawyers — and even veterans — arguing cases before the Supreme Court today has measurably declined over the decades, Meltsner says. Unlike in the U.K., for example, any lawyer who is a member of the Supreme Court Bar can file a case in the Supreme Court — and, if certiorari is granted, argue the case.

As the political stakes attached to the Supreme Court’s review heighten, those who get to argue cases before the court are increasingly a specialized group from the more prestigious firms — the “repeaters,” who are well-represented in certiorari petitions, or requests to have the Supreme Court review a case.

“What you see today is a smaller number of participants, a more experienced group, and cases that are more in the public eye, more significant, and increasingly representative of the polarized issues of the day,” Meltsner says.

In the past the court was much more likely to accept cases that were far less politically salient, he says.

“There were kinds of ‘lawyer’ cases — as I call them — that dealt with a whole range of issues,” he says. “That’s very different from today.”

A repository of recordings of historical oral arguments from Supreme Court cases is available online.

Tanner Stening is a Northeastern Global News reporter. Email him at t.stening@northeastern.edu. Follow him on X/Twitter @tstening90.