Published on

In this math seminar, the magician reveals his secrets

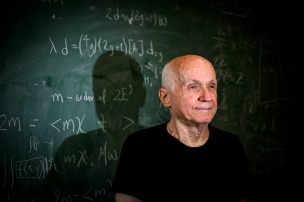

In Math, Magic, Games & Puzzles, longtime Northeastern mathematics professor Stanley Eigen uncovers the numerical principles behind popular card tricks — and helps his honors students teach them to kids.

Walking in to an honors-level math seminar on Northeastern University’s Boston campus in early September, you might expect to see graphing calculators, thick textbooks, algebraic equations and parabolas scratched on a marker-board — trappings of the serious work that the best STEM-focused students at a world-class research university are undertaking.

Instead, in Stanley Eigen’s class, you’ll see a flurry of shuffling playing cards; hear a dim cacophony of awed chatter. You’ll watch a grainy YouTube video of the ’90s-era celebrity magician David Copperfield, who, in between corny jokes and a terrible moonwalk, correctly identifies the seemingly random card that you, the home viewer, have pulled from your deck.

This is HONR 1310: Math, Magic, Games & Puzzles, for freshmen in Northeastern’s honors program. It covers the mathematical concepts underlying well-known card tricks and puzzles, but the more important takeaway is how to communicate them effectively. This is a service-learning course, and students must perfect the tricks in order to teach them to elementary- and middle-school-age kids in Boston-area partner programs.

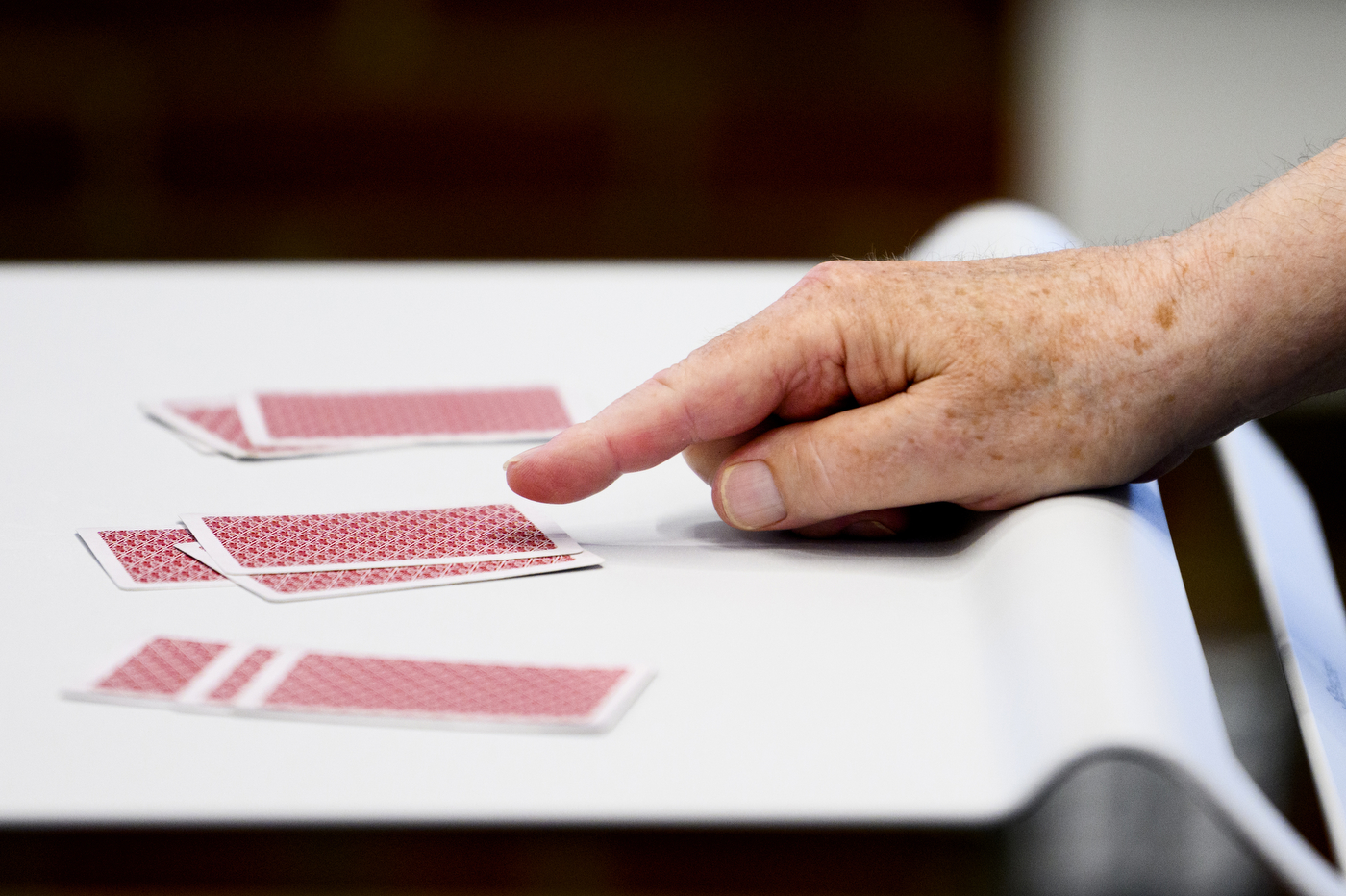

Today’s lesson, just the second of the semester, is devoted to card tricks that use “orbits” — predictable paths of a numerical system. Eigen starts with the “Nine Card Liar” trick. (You, readers, can now grab a deck and play along).

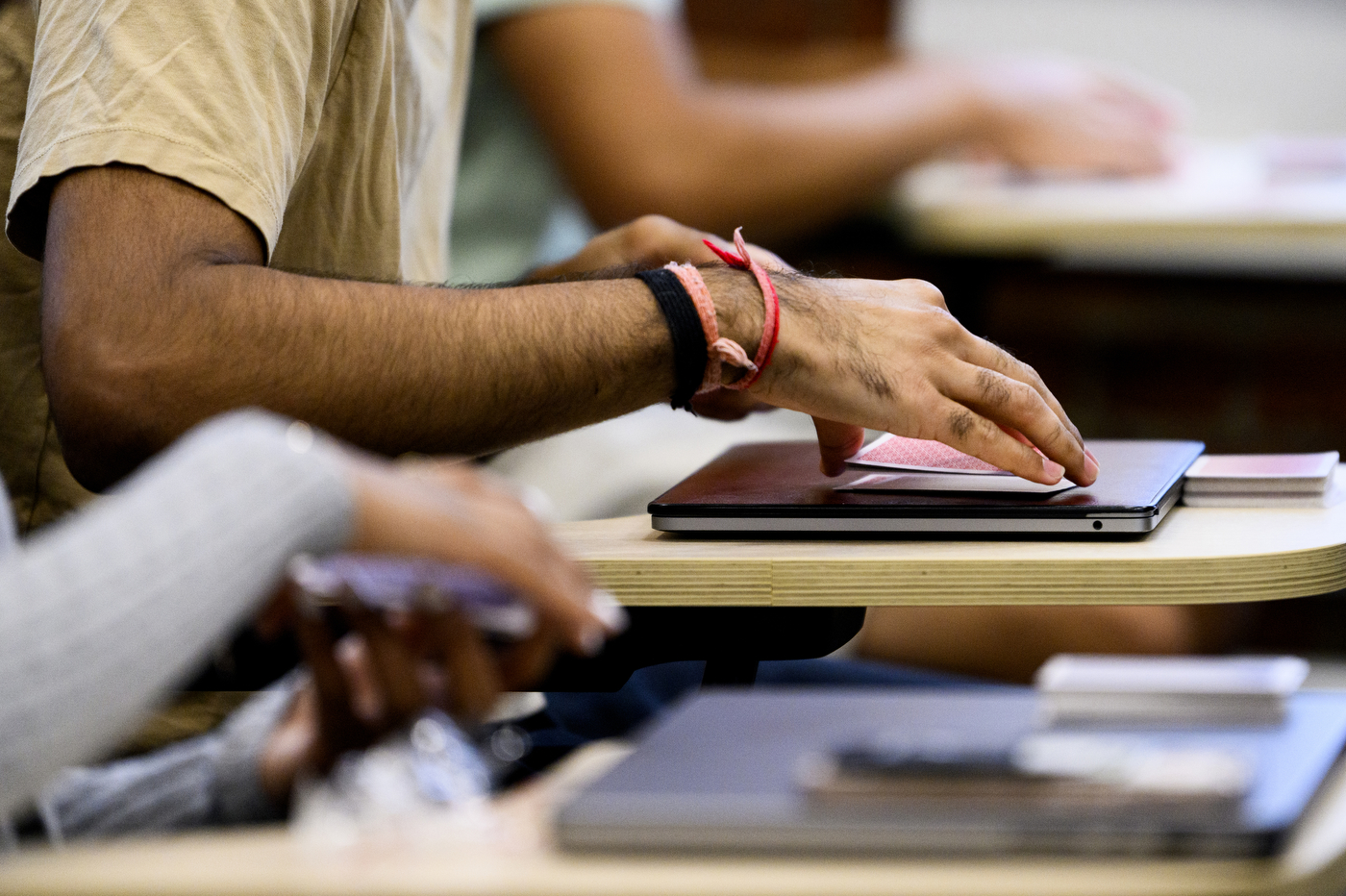

“Everyone, get yourself nine cards,” Eigen says. “Mix them up, or don’t, doesn’t matter. Now deal them out, three piles, one at a time, left to right.” The students, all of whom have been on campus for about a week, lay the cards out on the small desks, creating square grids.

“Pick up the middle pile,” he instructs. “Look at the bottom card and remember it.” I select the 10 of Diamonds. “Drop it on one of the piles, pick that whole thing up and drop it on the third pile. Everybody OK?”

This is a “spelling trick,” in which cards are shuffled around based on seemingly random words — the letters in a name, or the suit and value of a given card. Eigen continues: “Now think of your card, but lie and spell a completely different card.” He does the Four of Clubs, putting down a card each for the letters in F-O-U-R-O-F-C-L-U-B-S.

“Everyone spelled something different,” he says. “You lied, but the truth will solve everything. So take the top card, drop it on the table: T-R-U-T — and if you look at the H, it should be your card.” Sure enough, the 10 of Diamonds comes up. The students, all recognizing their own card, gasp and giggle.

Eigen explains that the trick works by locking in the trajectory — orbit — of the card at the outset. “It doesn’t matter what you spell,” he says. “Because of the length of the words, the card is always going to go third from top, third from the bottom, middle fifth.”

Variations work the same way. Some magicians use the letters in people’s names, colors, or random numbers called from the audience – keeping track of the card in the lineup is all that matters. “If you can add basic sums, you can do this trick,” Eigen says.

He takes out his flip phone, checks the time, and gives the students 10 minutes to practice. Will Kibel, a freshman computer science and game design combined major, turns around to practice on one of the small student desks, fumbling a few of the steps but eventually getting it right. “I have zero experience with magic,” he says in an interview a week later. So far, mastering it has proven more intimidating than the math, which is relatively simple. He’s been practicing at home. “I don’t really have the flow down but at least I know how to do the tricks,” he says.

This practice is at the heart of the class. HON 1310 is the only service-learning course the math department offers. As such, it is much less regimented than a typical math class. There are no prerequisites for enrollment (although Eigan says that incoming honors students have often taken at least pre-calculus), and it’s as much about connecting to a particular audience as it is about numbers. Eigan gives lectures on a few key topics, including strategies for the game NIM and common logic puzzles and riddles.

Beyond that, students explore further based on their own interests and what might be a good fit for children in programs including Chinatown Access, Boys & Girls Clubs of Dorchester and St. Stephen’s Youth Programs. Course materials include lots of YouTube videos from card sharks and famous magicians, along with more prosaic math tutorials.

“I like to get Penn & Teller because they have lots of jokes,” Eigen says. “If you’re going to talk to the kids, you may want to watch people doing it to get an idea of how they’re interacting effectively.”

Eigen has been at Northeastern for 41 years. His academic expertise is in ergodic theory, and he doesn’t consider himself a magician in the strictest sense. “I did magic tricks growing up, and I used to do shows when my niece or nephew had a birthday party,” he says. “When my kids were little, I learned how to do balloon animals, and I loved reading and figuring out how this stuff worked.”

That was enough for Solomon Jekel, a fellow four-decade veteran professor in the math department (the two are longtime office neighbors) to tap Eigen to teach Math & Magic in 2017. It’s been offered as a first-year honors seminar ever since. Unlike its subject matter, the course’s origin is perfunctory: “The math department needed a service-learning class,” Jekel deadpans, and he was tasked with designing it. “They wanted an original topic, and something math-related for the honors program. Stanley is the perfect person to teach a course like that.”

Eigen is also a perfect fit for freshmen away from home for the first time, just getting a feel for college in a major city. “He’s been a very welcoming presence,” Kibel says. “He’s not intimidating; very relaxed and friendly. It would be very easy to go into a math-based class and be terrified, but as a professor he’s great.”

Part of the College of Science, Northeastern’s math department is huge: 700 undergraduate majors, and over 1,000 when combined majors are taken into account. Though the course is singular, Math, Magic, Games & Puzzles represents a more conscious shift in communicating how math comes to bear on everyday life — all manner of work, of course, but play, too. “Some magic tricks connect to DNA analysis and coding theory. Some puzzles connect to logic and ethical dilemmas. Some games connect to social skills and economics,” Eigan’s syllabus reads.

Jekel says that with the rise of big data and statistical analysis, every field is looking for mathematicians. “It can be anything from a fairly rudimentary application to [something] on a high creative level,” he says. A lot of [mathematical] fields which were previously mostly theoretical are now being applied to data analysis. Because you need creative ideas to deal with the problems that arise.” This has helped to grow the math department alongside the university’s vaunted computer science, engineering and even journalism programs.

Kibel will be sharing his newly-acquired skills with the elementary schoolers at St. Stephen’s Youth programs. “It’s cool to be taking a class where you can give back to the community,” he says. “If you’re able to learn a concept and later relay that to kids that don’t have the same math understanding, that’s a useful skill for anyone.”

Schuyler Velasco is the campus & community editor for Northeastern Global News. Email her at s.velasco@northeastern.edu. Follow her on X/Twitter @Schuyler_V.