There are ghosts in your machine. Cybersecurity researcher can make self-driving cars hallucinate

Have you ever seen a dark shape out of the corner of your eye and thought it was a person, only to breathe a sigh of relief when you realize it’s a coat rack or another innocuous item in your house? It’s a harmless trick of the eye, but what would happen if that trick was played on something like an autonomous car or a drone?

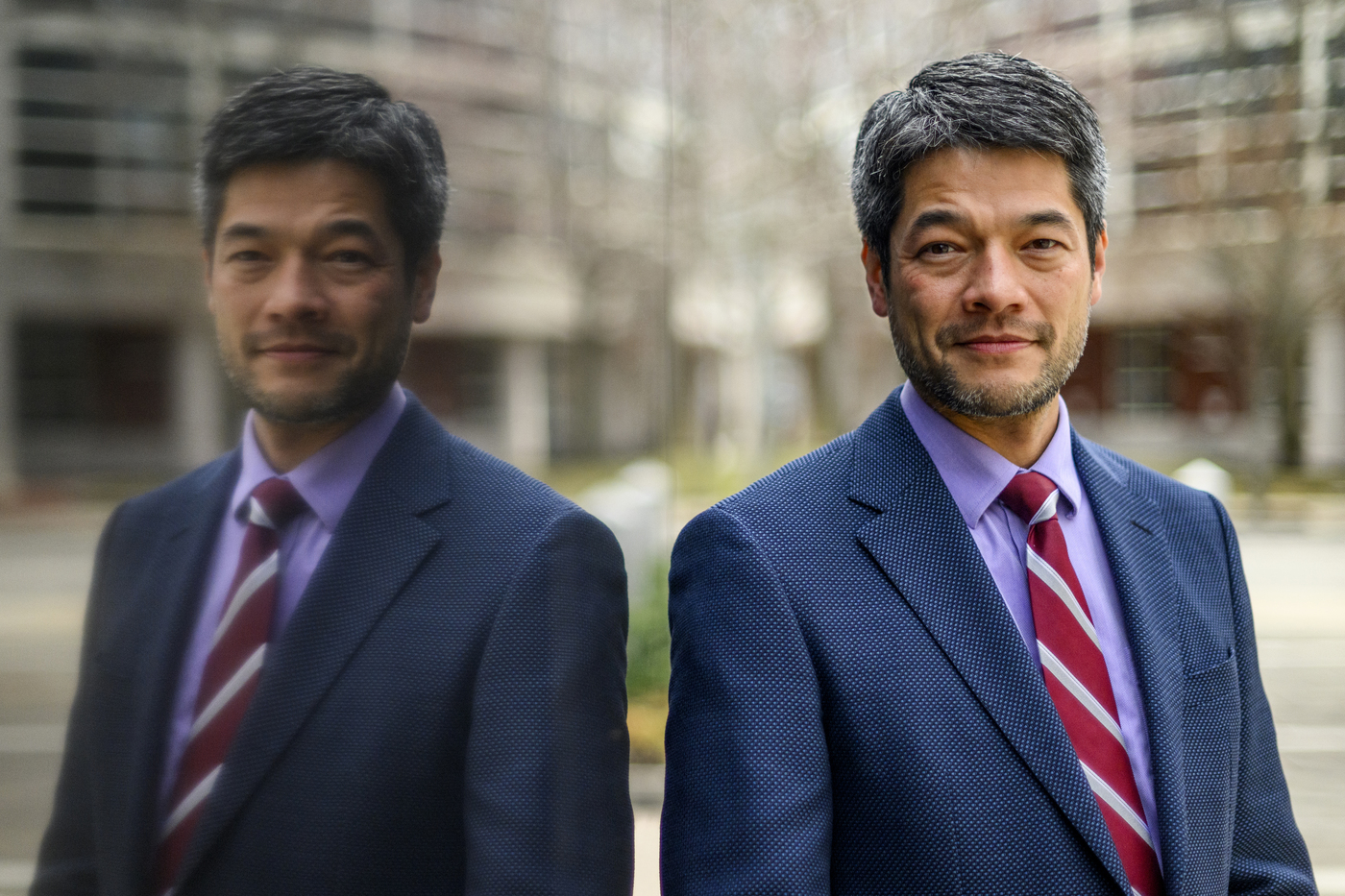

That question isn’t hypothetical. Kevin Fu, a professor of engineering and computer science who specializes in finding and exploiting new technologies at Northeastern University, figured out how to make the kind of self-driving cars Elon Musk wants to put on the road hallucinate.

By revealing an entirely new kind of cyberattack, an “acoustic adversarial” form of machine learning that Fu and his team have aptly dubbed Poltergeist attacks, Fu hopes to get ahead of the ways hackers could exploit these technologies –– with disastrous consequences.

“There are just so many things we all take for granted,” Fu says. “I’m sure I do and just don’t realize because we abstract things away otherwise, you’ll never be able to walk outside. … The problem with abstraction is it hides things to make engineering tractable, but it hides things and makes these assumptions. There might be a one in a billion chance, but in computer security, the adversary makes that one in a billion happen 100% of the time.”

Poltergeist is about more than just jamming or interfering with technology like some other forms of cyberattacks. Fu says this method creates “false coherent realities,” optical illusions for computers that utilize machine learning to make decisions.

Similar to Fu’s work in extracting audio from still images, Poltergeist exploits the optical image stabilization found in most modern cameras, from smartphones to autonomous cars. This technology is designed to detect the movement and shakiness of the photographer and adjust the lens to ensure photos are not a blurry mess.

“Normally, it’s used to deblur, but because it has a sensor inside of it and those sensors are made of materials, if you hit the acoustic resonant frequency of those materials, just like the opera singer who hits the high note that shatters a wine glass, if you hit the right note, you can cause those sensors to sense false information,” Fu says.

By figuring out the resonant frequencies of the materials in these sensors, which are typically ultrasonic, Fu and his team were then able to fire matching sound waves toward camera lenses and blur images instead.

“Then you can start to make these fake silhouettes from blur patterns,” Fu says. “Then when you have machine learning in, say, an autonomous vehicle, it begins to mislabel objects.”

While researching this method, Fu and his team were able to add, remove and modify how autonomous cars and drones perceived their environments. To the human eye, the blurred images that Poltergeist attacks produce might not look like anything. But by disrupting a driverless car’s object detection algorithm, the silhouettes and phantoms conjured by Poltergeist attacks transform into people, stop signs or whatever the attacker wants the car to see or not see.

For a smartphone, the implications are significant, but for autonomous systems mounted onto fast-moving vehicles, the consequences could become dire, Fu says.

As one example, Fu says it’s possible to make a driverless car see a stop sign where there isn’t one, potentially resulting in a sudden stop in a busy road. Or, a Poltergeist attack could “trick a car into removing an object,” including a person or another car, making the car roll forward and run through that “object.”

“That depends on a lot more, like the software stack, but this is starting to show cracks in the dam of why we trust this machine learning,” Fu says.

Fu hopes to see engineers design out these kinds of vulnerabilities in the future. If they aren’t, as machine learning and autonomous technologies become more commonplace, Fu warns that these threats will become a bigger problem for consumers, companies and the world of tech as a whole.

“Technologists would like to see consumers embracing new technologies, but if the technologies aren’t truly tolerant to these kinds of cybersecurity threats, they’re not going to be confident and they’re not going to use them,” Fu says. “Then we’re going to see a setback for decades where technologies just don’t get used.”

Cody Mello-Klein is a Northeastern Global News reporter. Email him at c.mello-klein@northeastern.edu. Follow him on Twitter @Proelectioneer.