Published on

It’s all fun and games. This class takes play seriously

Social skills. Problem solving. Therapy. In Emily Mann’s Science of Play class, Northeastern students learn how critical play is for children—and themselves.

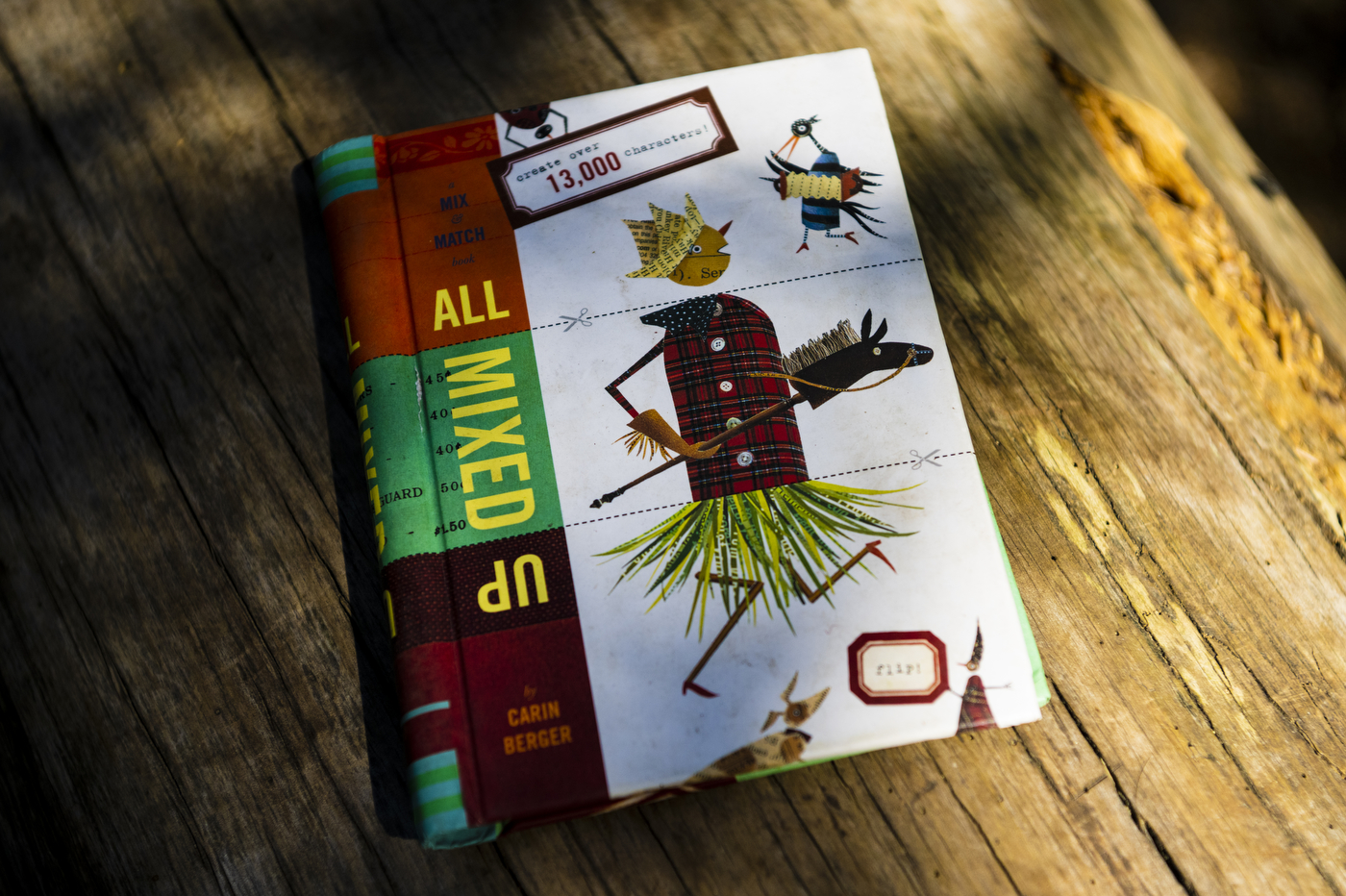

Emily Mann stops her lecture and turns to the class. “We’ve been sitting for hours; let’s play a little bit,” the Northeastern University human services professor tells the 15 honors students assembled in a sunny corner of Richards Hall on a Tuesday afternoon. She takes out a stack of multicolored circles the size of saucers with Velcro on one side, and the students affix them to the carpet, into a grid with no particular color pattern. They assemble into a circle and take turns hopping from one circle to another, trying to guess a path that another student—designated the “planner”—has decided on in their head.

“Yes. Yes. Yes. No!” the planner calls, as, one by one, the players collapse in frustrated laughter. Eventually, one guesses the sequence correctly, hops all the way across the grid, and wins the game. Next is a supercharged version of “Simon Says,” which culminates in the players trying to do one thing with their bodies (take a step to the right, for instance), while saying the opposite (“Left!”).

Go ahead and try it. It’s hard!

The games serve as a respite for the students, who are smiling and relaxed as they settle down for the remainder of the class discussion. But Mann also uses them to demonstrate, in an immediate, tangible way, how playing together nurtures qualities like social awareness and problem solving. One student, Kiara Wint, wins the color sequence game after asking for and receiving hints from her classmates.

“There were no rules against that, right? I didn’t say [so],” Mann tells the group. “You asked for help. That’s a skill: to ask, when we are in trouble, when we need support in very small ways. It’s really great practice to be able to get it.”

Mann has taught Science of Play at Northeastern every summer since 2017, both as a human services course and an interdisciplinary seminar in the university’s honors program. Also part of Northeastern’s Community Engaged Teaching and Research offerings, the course is equal parts classroom time and site visits to play spaces around Boston—the city’s Children’s Museum, public schools, area playgrounds.

Later in the week, they head to the Arnold Arboretum in the Jamaica Plain neighborhood to observe and play with children enrolled in Boston’s outdoor preschool network. Dressed in reflective yellow vests and warm clothes, the kids, all under age 5, are dropped off, picked up, and spend the bulk of the day outside in the arboretum’s lush fields. They do the usual preschool things, like reading, drawing and circle time. But there’s also more digging in the dirt and balancing on (and falling off) high boulders and fallen trees than at your typical preschool.

Obviously, Science of Play is a vital course for any Northeastern student setting out on a career working with children. The syllabus touches on the history of play and theories of childhood development, as well as its clinical uses. (Play is commonly used as a form of therapy.)

The class also has a social justice component, touching on issues of equal access to play, disability rights, and barriers to play that exist across the socioeconomic spectrum. Students majoring in social work, nursing, education, social sciences, and public health are mainstays in the class. But as an honors seminar, it is open and, according to Mann, applicable to students in any field of study at Northeastern. “Going into business requires risk assessment and social skills,” she says in an interview. “Computer science is problem solving. So students come from all over.”

What’s more, Mann says, the class isn’t just about children. As the games suggest, college kids need play, too. And she encourages the students to think about its usefulness at any age. Claire Kobylski, a second-year student with a combined major in health science and business administration, took Science of Play last year. She’d like to work in elder care, and for her final project, she researched how residents at the Susan S Bailis Assisted Living facility near campus engage in play. For that population, the social aspect tended to be more important than the game itself. “A common theme was games that are easy to play and understand, that a lot of people can participate in,” she says. “Something like Bingo or simple card games: straightforward, but still so fun. You can joke around as it’s happening.”

The mindset is shifting more towards thinking about the students individually and what they need

Beyer Bullard, a third-grade teacher in Brookline, Massachusetts

For kids, play helps make sense of how they move through the world. This week, the focus, both in class and on the arboretum field trip, is on risky play, which Mann and many other childhood development experts argue is vital, if fraught. She shows a mini-documentary about The Land, a playground in Wales that looks like a junkyard, where kids are invited to try out all sorts of hazardous activities. Children climb rickety-looking trees and use sharp saws to fashion bats out of wood planks and nails; a group of boys set a fire in an old sewer tunnel and joke about killing each other while a staff member stays close, but doesn’t interfere. The class gasps audibly as they watch.

The idea behind The Land, Mann tells the class, is that giving children space to navigate risky environments will help equip them to make decisions about safety and risk as adolescents and adults, when the stakes are higher. Letting kids figure things out themselves, she says “is really empowering. You can just smell the self-esteem.”

The discussion prompts the students to reflect on their own childhoods: one recalls playing with fireworks; another on her overprotective mother who, even now, sends her news stories about people being maimed in freak accidents. “Especially for this week’s module, a lot of students are talking to their parents about the class,” Mann says.

Science of Play’s very existence in the Northeastern course catalog represents a shift in thinking about childhood education and development, even since Mann’s university students were elementary schoolers themselves. As No Child Left Behind-style policies swept through the nation’s school systems in the early 21st century, an emphasis on quantifiable academic benchmarks often came at the expense of arts, physical activity, and recess, according to critics. Beyer Bullard, who took Science of Play last year and is currently working as a third-grade teacher in Brookline, says some school districts are shifting back to a more holistic approach to education.

“In general, the mindset is shifting more towards thinking about the students individually and what they need,” Bullard says. “In Brookline, we teach a whole class on social emotional learning. It’s a designated chunk of our day. And it’s shifting away from play as a reward, to more as play as a necessity.”

Bullard says that Mann’s class has had a huge influence on how he runs his classroom.

“Today we went on a field trip in the morning, and we missed their usual recess time,” Bullard recounts. “We get back and the kids are bouncing off the walls. So I decided to [cancel] our literacy block, writing and reading, and just to come outside instead.

Of course, he says, reading is important. But the social emotional learning skills developed during recess are equally vital—yet undervalued.

“I see it every day,” Bullard says. “I take them outside. And they learn how to navigate relationships, resolve conflicts, set up games, how to make rules. They learn how to meet new people, to play nicely with others, they learn how to make smart choices, safe choices. All this stuff, and I don’t have to do anything.”

Bullard hosts the Science of Play students on one of their field visits in June, so they can see firsthand how he uses what he learned in his classroom. And Mann hopes that students will also be inspired to think about the role of play in their own lives. “It has helped me rethink my relationships, not only with young children, but with teens with college students,” she says. “Are we giving kids what they need for healthy balance here at Northeastern?”

Schuyler Velasco is a Northeastern Global News Magazine reporter. Email her at

s.velasco@northeastern.edu. Follow her on Twitter @Schuyler_V