Are the US and China headed for a Cold War?

Are the U.S. and China headed for a Cold War? Recent headlines sure make it seem like an ideological clash is imminent—if not already ongoing.

After the U.S. earlier this month spotted what it said was a Chinese spy balloon in U.S. skies, officials canceled a planned diplomatic visit to Beijing. It was the second notable diplomatic drama in as many years after Nancy Pelosi’s trip last summer highlighted growing tensions between the two countries.

Under orders from President Joe Biden, the U.S. military shot down the high-altitude balloon after it traveled over several military sites and across the country. In response, China threatened to retaliate, saying it has the right to “take further actions” for what it deemed “an obvious overreaction and a serious violation of international practice.”

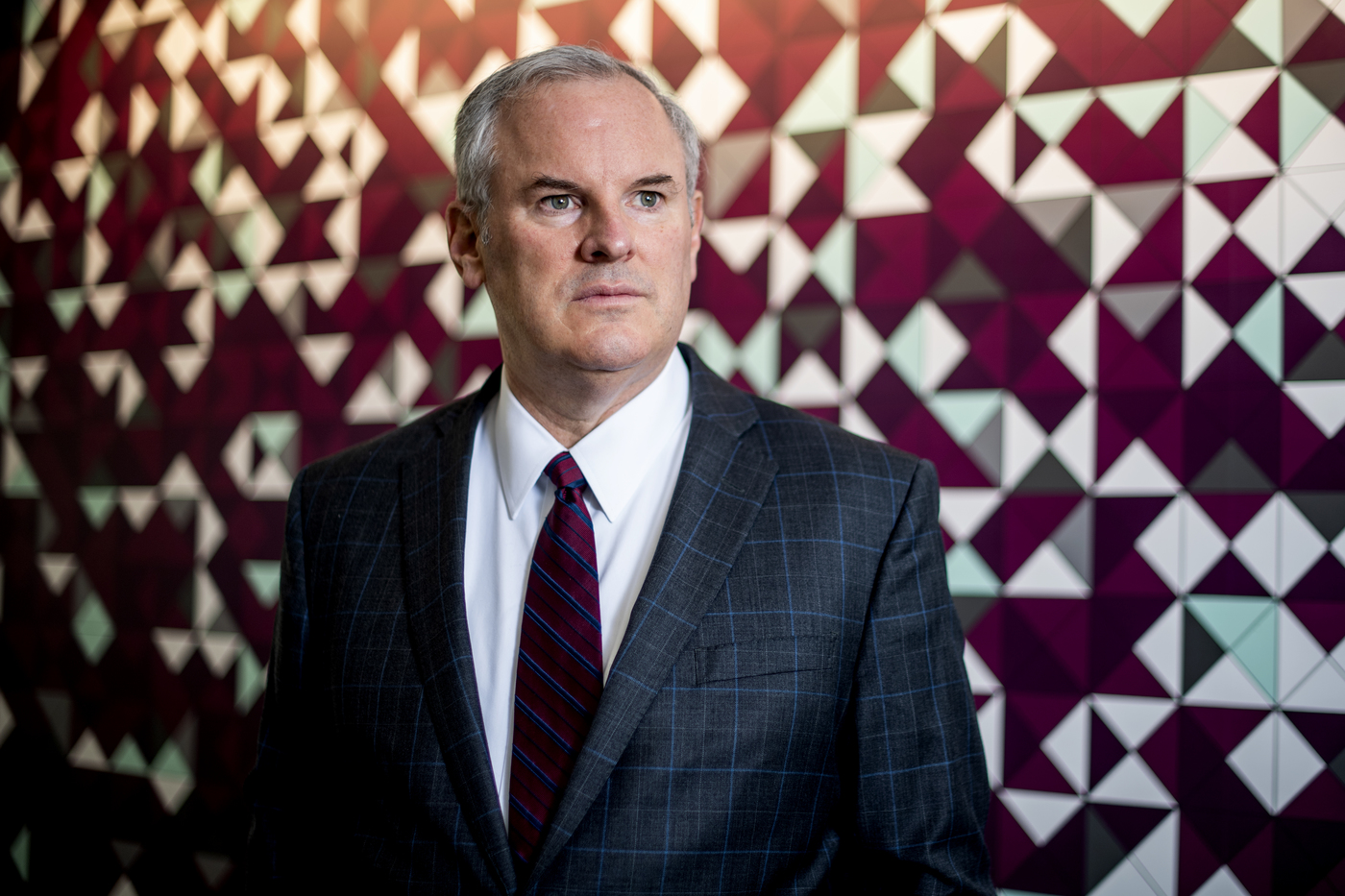

The crises show that the need for diplomacy between the U.S. and China has never been higher, experts say. The risk for military conflict is real, says Stephen Flynn, founding director of the Global Resilience Institute at Northeastern. But unlike the bloodless geopolitical struggle between the U.S. and the former Soviet Union that gave the Cold War its name, the growing rift between the U.S. and China is complicated by the two countries’ “dependencies and interdependencies,” he says.

“The reality is that when we were in conflict with the Soviet Union, all of our systems were in opposition to each other,” Flynn says. “It was a Democratic form of government versus a Communist authoritarian government. The Soviet Union’s economic model was entirely separate from the Western model. The threat of military conflict was bedded on top of that, making for an incredibly combustible set of circumstances.”

For one, the U.S.’s “deep economic integration” with China, which Flynn says is a distinguishing feature of their relationship, was on display during the COVID-19 pandemic, when supply shocks revealed just how dependent the U.S. was on Chinese manufacturing for, among other things, vital medical supplies.

“What’s been unique about our relationship with China is the depth of the economic ties,” Flynn says. “That really took off and became evident in the ‘90s.”

Another key difference is that China’s military prowess doesn’t yet stand up to the U.S’s.

“China has always aspired to be viewed as a superpower and to have the ability to contest the United States militarily, economically and socially,” Flynn says.

A superpower must be able to exercise power globally, and exhibits “economic, military and ideological” influence worldwide, says Mai’a Cross, dean’s professor of political science, international affairs and diplomacy, and director of Northeastern’s Center for International and World Cultures.

“I wouldn’t characterize China as a superpower,” Cross says.

But talk beyond Beijing about its growing influence has, Cross says, emboldened the East Asian country to adopt a more aggressive foreign policy—one that directly challenges its adversaries abroad, while looking to expand its regional influence.

Of course, whether the two nations are on a path toward direct conflict depends on your definition of “cold war.” On the one hand, the term refers specifically to the historical period of geopolitical tension between the U.S. and Russia. Outside of that context, “cold war” becomes somewhat nebulous.

“One way to look at a ‘cold war’ is as a scenario or situation that successfully avoids becoming a hot war,” Cross says.

In other words, it could describe tension between two countries “otherwise on the brink of war with each other,” were it not due to the fact that “they’ve managed to keep things at a simmering level.”

Cross says she doesn’t believe the U.S. and China are in a Cold War. “They are certainly in very strained relations right now and definitely at a diplomatic low point,” she says.

What the balloon saga illustrated was that the “U.S. and China relationship is a fraught one,” Flynn says.

“It also showed that, on issues of national security and the potential for conflict, we’re spying on each other. That all came to the forefront with this balloon,” he says.

Some experts have suggested that the term “cold war” has been bandied about in ways that are dangerous.

“Let’s not call the U.S.-China competition a ‘cold war.’ This ongoing conflict ought to have a name all its own,” James Jay Carafano, a leading national security expert, writes for The Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank. “Today’s standoff with Beijing is as different as World War II was from World War I.”

Carafano notes that the Soviet Union was “a monstrous military machine and a struggling economic power,” whereas China, today, is “a massive economic competitor and a rising military challenge.”

“The threats have to be seen differently,” he writes.

Tanner Stening is a Northeastern Global News reporter. Email him at t.stening@northeastern.edu. Follow him on Twitter @tstening90.