The Department of Homeland Security, ‘not set up for success,’ navigates rocky 20 years. How are things today?

Twenty years ago last month, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security was created in response to the 9/11 attacks.

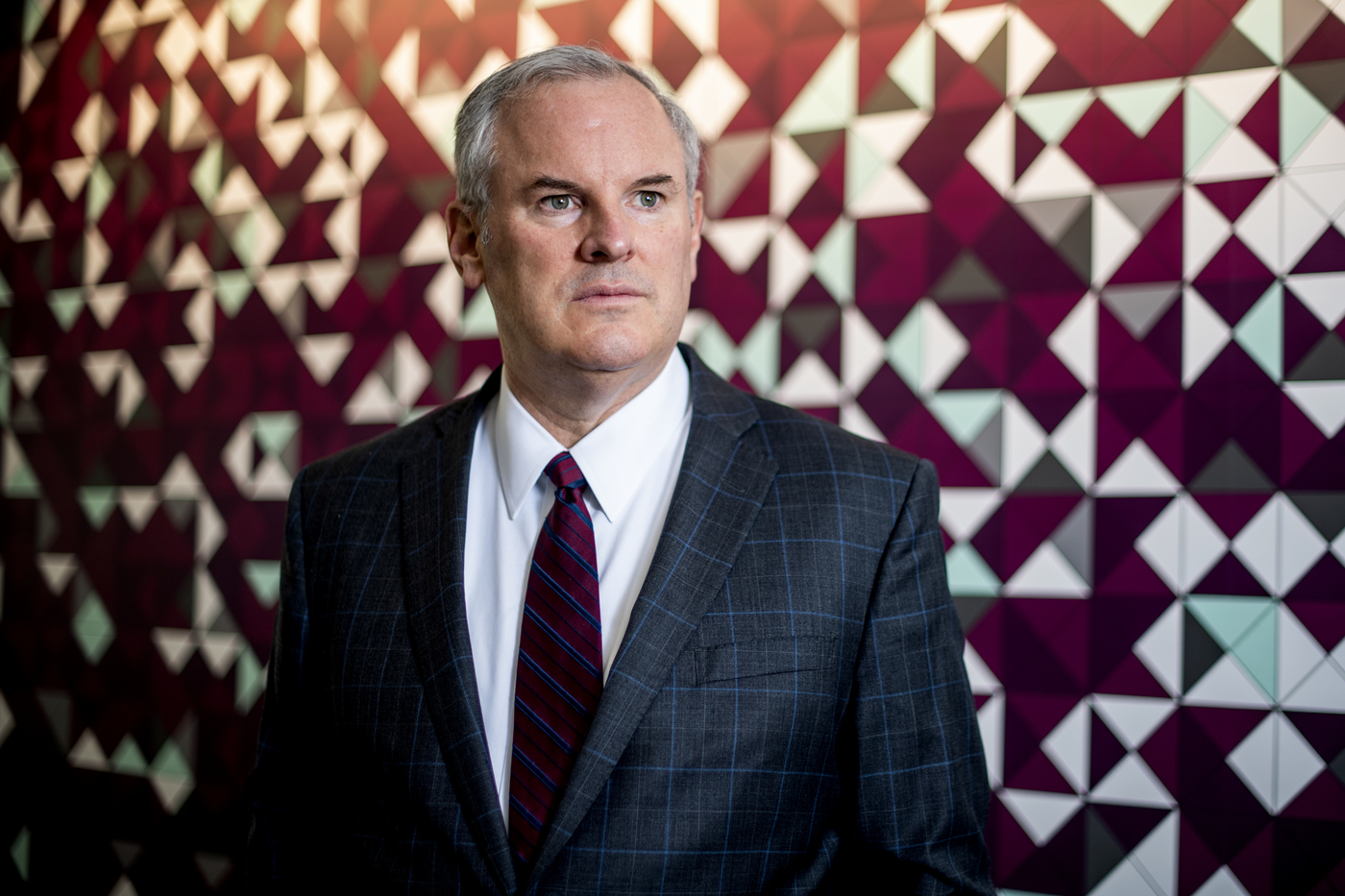

Stephen E. Flynn, director of Northeastern University’s Global Resilience Institute, was there at its inception. A staff member for the Hart-Rudman Commission, which both shaped and envisaged the creation of the federal department, Flynn had been thinking about national security and the threats facing the U.S. for decades—well before the unforgettable terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon.

News@Northeastern recently sat down to chat with Flynn, who was critical of the department in its early years for its narrow focus on terrorism. He says there’s still a lot of work to do. His comments have been edited for brevity and clarity.

You were part of the Hart-Rudman Commission, which outlined a vision for what would become the Department of Homeland Security. Set the scene for us. It’s the late ‘90s. What are security experts concerned about?

One of the main findings of the commission was that the greatest challenge confronting the United States, from a national security perspective, would be a catastrophic terrorist attack on our soil—and that the nation was not prepared to deal with such an attack. That was rolled out on Jan. 1, 2001, to a collective yawn in Washington D.C.

Then 9/11 comes around and suddenly the report gets dusted off. It was picked up in particular by [former] Sen. Joe Lieberman, who then advocated for one of the recommendations, which was combining the border agencies and [Federal Emergency Management Agency] together into a new department, essentially focusing their efforts. Security was seen as a Republican strong suit. And Lieberman, you may recall, ran as a vice presidential candidate with Al Gore and was seen as a potential rival in the 2004 election.

So the Bush administration had to get out in front of this challenge. That political dynamic ultimately led to the creation of the Department of Homeland Security.

When the department was up and running, what challenges did it face as a fledgling government body?

Photo by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

It was put together in a hurry and without a lot of enthusiasm. A reaction to the political climate at the time. It was not set up for success. One of the issues, as you just pointed out, was that it was built almost entirely around the terrorism risk when there were a lot of other hazards. There was also the problem that, when the Bush administration stood it up and brought these agencies together, they were worried that creating a new federal department would give the appearance of big government. And Republicans are the party, supposedly, of smaller government.

To square that circle, they essentially said they would treat it like a big merger. They said they were going to get all these synergies out of bringing these agencies together. So what they ended up doing was set it up without any real staffing. They essentially taxed the agencies that fell into the department to send their senior managers on one- or two-year details; and then made it almost a political dumping ground.

They created 300 political appointee positions that they rotated people in and out of. By the time we got to 2009, when the Obama administration started, only one quarter of the Department of Homeland Security’s staff had been there for more than two years. I remember frequently visiting the department—there was always a new set of faces, talking about the same challenges. But for them, it was always brand new.

The other big issue was that federal agencies in the department like FEMA, the Coast Guard, and Customs and Border Protection needed upgraded capabilities to do their missions, but the resources were spent more on new technologies rather than in investing in people to include training and education. And thirdly, they had to sort out the “federalism” challenge. Executing homeland security is ultimately done at the state and local levels, right? And that created issues for the Bush Administration which was reluctant to direct state and local governments on what they should be doing.

The bottom line was that getting DHS off to a strong start was simply not a priority for the White House and Congress in its early years. The focus was on the War on Terror overseas and the FBI which is in the Department of Justice was the lead agency for counterterrorism at home. The Department of Homeland Security was trying to find a way to work with governors, mayors, and critical infrastructure operators—most of who were in the private sector—but it struggled getting them to really step up their efforts. A lot of it was, ‘Hey, you guys should do more. Here is some grant money you can compete for.’ It was never about trying to mobilize the homeland; instead DHS ended up playing basically a minor support role to states and localities, where most of the capacity ultimately needs to be.

The last problem was an almost complete failure to engage civil society After 9/11, American were largely told that their role was to just keep “shopping and traveling.” “Get back to your daily lives and we’ll take care of you,” the federal government essentially said. And that was something I was most critical about. At the end of the day, our greatest asset for dealing with major shock and disruptions is always civil society, because that’s where the rubber meets the road. When there is a pandemic, as we saw most recently, or any major disaster, it’s all going to come down to local organizations, nonprofits, and faith-based groups, etc. They’re going to have to figure out how to cope with these big disasters and catastrophes. The challenge is how to empower them with the knowledge and resources to play that role.

How is the department doing today?

The department definitely has moved more into an “all hazards” approach. Appropriately, homeland security has been broadened from terrorism, with the issue of cybersecurity getting much more attention. Belatedly, after Hurricane Katrina in 2005, there was a recognition how important FEMA is to the mission of homeland security. As FEMA move from being a bit of an orphan in DHS at the start to get new staff and resources, that’s really allowed the department to actually be more effective in addrerssion to all hazards to include natural disasters as an element of homeland security versus an almost exclusive focus on the terrorism threat. That’s all good in my view.

On the second issue of the department still struggles to manage the agencies that fall in it to include the Coast Guard. CBP, ICE, and FEMA; those are the big players. But the Secret Service is also in there; and there’s a bunch of small agencies that were sent to DHS. All those agencies have their original congressional overseer. For instance, Customs and Border Protection is overseen by congressional treasury committees, because it used to be in the Department of Treasury. So what that means is that these agencies essentially have a way to end-run their own leadership by going directly to Congress to get their budgets supported there. Because that’s where the rubber hits the road. And it’s very difficult for the leadership of the department to herd the cats, so to speak, because at the end of the day, Congress allocates the fund.

These agencies basically have one eye to their congressional masters, and another eye to the administration. So it’s been a real challenge to essentially manage these agencies in a way that makes them all pull together, which was the initial vision. There also hasn’t been near the investment in these agencies to improve their training and education. After 9/11, everything was about buying new technology; we wanted to impress people with stuff. But the actual investing in people to actually do the work: not so much.

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.