When it comes to religious appropriation, Northeastern professor says it could be better to borrow more, not less

Is Cardi B posing the Hindu goddess Durga a form of cultural appropriation? What about American women wearing hijab as a form of solidarity? Or Western people practicing yoga?

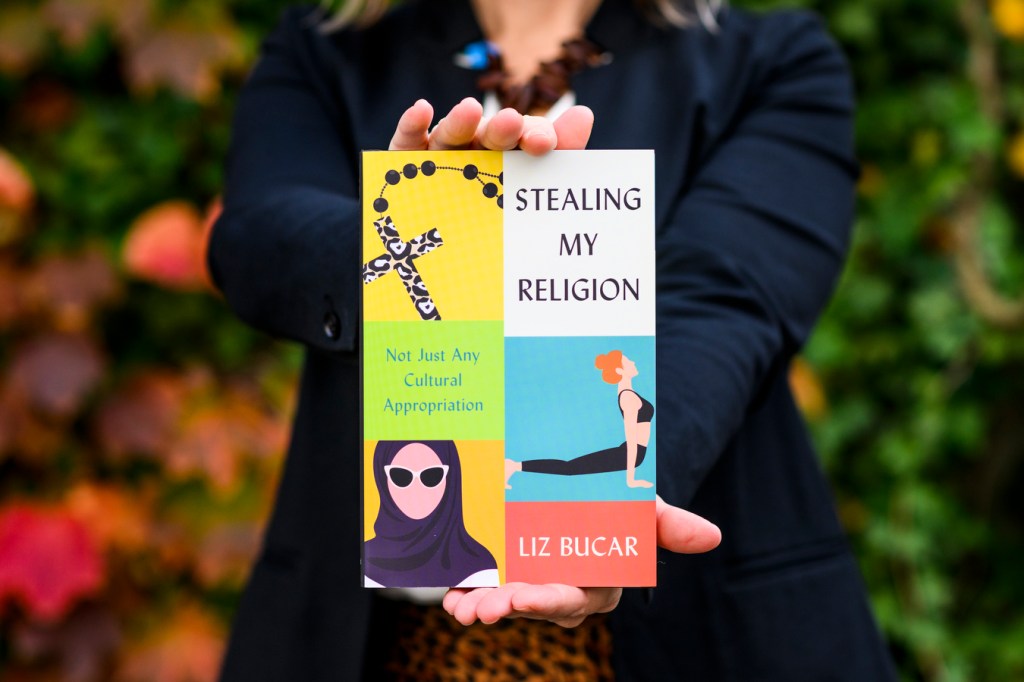

While cultural appropriation has become a common topic of discussion in recent years, in everything from the Great British Baking Show to Halloween costumes, the concept of religious appropriation has been left largely untouched. In her new book, “Stealing My Religion,” Liz Bucar, a professor of religion at Northeastern, shines a spotlight on this “particularly messy form of cultural appropriation,” what it reveals about inappropriate cultural borrowing more broadly and what can come out of these often uncomfortable conversations.

“Being uncomfortable can be productive,” Bucar says. “It’s not about shaming people, but it’s about trying to provide some framework for conversation and reflection.”

For Bucar, there is a difference between religious borrowing and religious appropriation. Religious borrowing is fairly common between religious communities, she says, to the point where it’s nearly unavoidable. The boundaries between different religions–and cultures–are not as solid as the debate around cultural appropriation would have people believe. Bucar says cultural borrowing is “sometimes just the way that religions interact or … religion works.”

Religious appropriation is what happens when someone who is explicitly an outsider from a religious community cherry picks aspects of a religion to use in their own lives. Bucar says even people who are keenly aware of cultural appropriation often don’t think critically about appropriating traditions or attire from religious communities. Part of the reason, she says, is that most religions are powerful institutions that are seen as non-problematic targets for cultural appropriation.

“That misunderstands the complexity of religious communities,” Bucar says. “You’re not doing things that will only have effects on the institution or the hierarchy but also believers.”

Not every case of religious borrowing is appropriation–and Bucar admits she is not trying to provide a convenient checklist of dos and don’ts–but the harm and offense it can have within religious communities is serious, she says.

“There are forms of offense that are minor, like they upset your sensibilities, and then there are profound offenses that are offensive to who you are,” Bucar says. “They feel violent, they disrupt how you see the world, how you see yourself, your core values.”

The popular “sexy nun” Halloween costume is an example of religious appropriation that, for some Christians, could qualify as deeply offensive. Those outside the community might think of the nun’s habit as just a piece of clothing, but for those within the community, that piece of clothing is directly tied to their beliefs and values.

“It’s not only an expression of a value like modesty but how modesty is created,” Bucar says. “There’s a lot at risk in religious appropriation because it’s not just culture. It’s culture tied to divinity, god and ultimate concerns.”

Bucar doesn’t think people who wear the “sexy nun” costume are trying to be offensive. Just like she doesn’t think those who started wearing a hijab, a head covering for Muslim women, as a show of solidarity after the Christchurch mosque shooting are trying to offend Muslims. Even when these actions have “good liberal intentions,” Bucar says this kind of appropriation can have “illiberal results.”

Bucar admits that she first saw the solidarity hijab as an incredible moment of connection between Western feminists and Muslim women. But, she quickly realized for many Muslim women, it meant something different. It was centering non-Muslims in the conversation and, despite the best intentions, exacerbating gender Islamophobia in an attempt to combat it, she says.

“It shifted our attention away from that community and things that really needed to change structurally to prevent that kind of violence from happening,” Bucar says.

Bucar hopes that by talking critically about cases like this, it will expand the conversation about cultural appropriation more broadly. She says the conversation is very polarizing, often because people insist on solid cultural boundaries that are more messy and porous than most people acknowledge.

“It’s really easy to see no one can own religion, so it starts to raise some of those questions about hybridization and how that’s just how culture develops and it’s also how religion develops,” Bucar says.

All of these examples shouldn’t deter people from religious borrowing, though, Bucar says. In fact, she encourages people to borrow more, not less.

“If you want to engage in religious practices, I want you to lean in further and understand the religious practice, understand the community, understand the context of that practice, understand the history so you know what you’re borrowing,” Bucar says.

By borrowing more, Bucar says people will learn more about what’s appropriate and inappropriate and become more careful borrowers. It sparks a conversation about a topic that Bucar says is not talked about, only fought about. She’s not trying to discourage people from practicing yoga. She’s trying to encourage people to ask critical questions about their yoga practice: Are there ways to do yoga that don’t exploit labor? Are there ways to do yoga that don’t de-center South Asian people and their traditions?

More than that, learning about others might also help people learn something new about themselves.

“That’s a lot of what really being serious about diversity is,” Bucar says. “It’s not just tolerating difference because that still assumes an us-them hierarchy. We should be letting diversity change what we understand to be good, right and true in the world. It really shifts our values. It shifts how we understand reality.”

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.