‘We’re all in this together.’ East Village becomes first Northeastern dorm to offer composting

Some students on Northeastern’s Boston campus will notice a new feature in their dorms this week.

When it’s time to take out the garbage and they head to the trash room, residents of East Village will see composting bins. East Village, which houses around 700 students, now offers daily food composting, and students are taking advantage of this opportunity to make a difference.

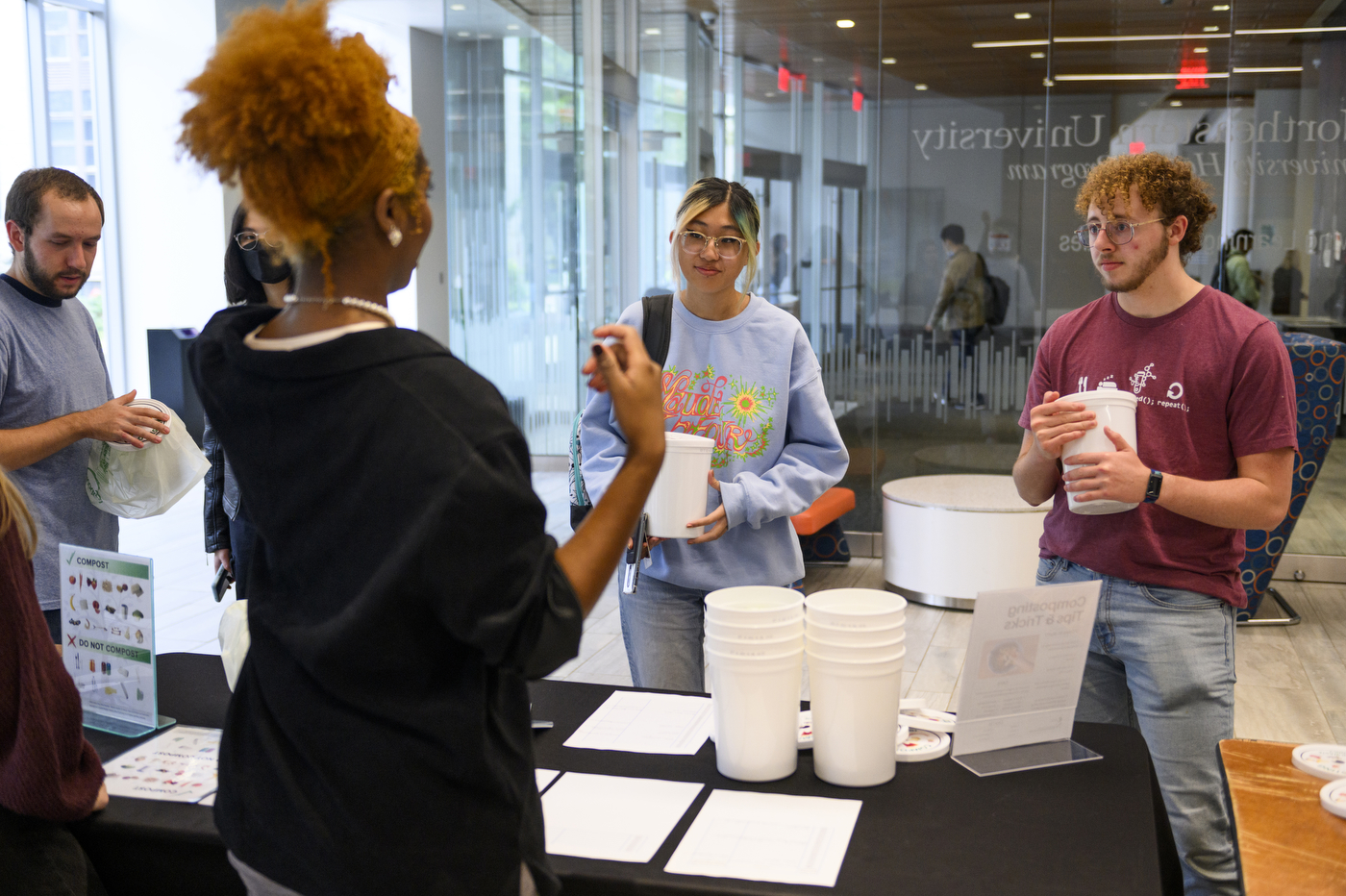

“I think it’s really cool that we have it available because I like to cook, so I have a lot of food waste,” third-year student Elana Lane says. As part of last week’s program launch, Lane helped spread awareness and distribute composting bins to students at a table on the ground floor of East Village.

The program is a small step toward combating a huge problem, says fourth-year student Madison Mcdermott, a founding member of CANU, the composting advocacy group on campus. Food waste is a lot more harmful to the environment than one might think, she says. Since food waste in landfills doesn’t have as much access to oxygen, it doesn’t break down properly and instead releases methane gas into the atmosphere.

When food waste is set aside, however, it becomes a rich soil that can be used for farming. “It’s a really great way to reduce emissions and make a large impact,” Mcdermott says.

Indeed, Susan Higgins calls it “one of the single best steps you can take” to combat climate change. Higgins manages all campus waste as associate director of materials and recycling in the facilities department.

According to Higgins, Northeastern creates about 10 to 15 tons of food waste each week. Massachusetts law requires university food services to compost, and this started in 2006 with food scraps in dining halls.

“Over the years we were able to expand it and move it into the student side of the dining hall,” she says, including plate scraping programs. Higgins also expanded composting to all eateries on campus, including Dunkin’, Tatte and Wollaston’s.

But the dormitories were notably absent from the program, and, as it turns out, it is something students really wanted, according to surveys conducted by CANU.

Facilities decided to give it a shot. In April, they completed a pilot at Spear Hall, which Mcdermott calls a “huge logistical success,” and another pilot program continues in Building V on the Burlington, Massachusetts campus.

The programs have been successful at reducing food waste as well as showing students and staff that composting isn’t a hard habit to form. “It’s actually a lot easier than it appears,” Mcdermott says.

At East Village, students are provided with small, leak-proof bins—they were once yogurt bins that were washed and donated by NU Dining—and compostable bag liners. The bins are small so as to encourage students to empty them often and avoid attracting bugs.

Students use the bins to dispose of food waste, including bones and dairy, and when the bin is full, they drop the bag in the trash room in East Village.

That’s where CERO Cooperative, Northeastern’s composting partner, comes in. They arrive on campus seven days a week and empty the composting containers into a truck, which brings them to Hidden Acres Farm in Medway, Massachusetts. The materials are dumped out and turned, and from there, “it just breaks down into a nice, clean soil,” Higgins says.

The East Village pilot program will continue through the end of the academic year. During that time, Higgins hopes to see 5% or less contamination, or non-food items, in the composting bin. She wants to see about a third or more of students participate, and see a decrease in food odors coming from trash compactors. Mcdermott anticipates that there will be bumps on the road, but that they will conquer them.

If the pilot does succeed, Higgins hopes to see it continue and expand to other dorms until it becomes as normal to students as recycling. “Once you’re doing it, you just don’t want to not do it,” she says. Mcdermott wants to spread the word so that students will compost off campus as well, especially since Boston now collects food waste along with trash and recycling.

In the long run, Mcdermott wants to see hearts and minds change when it comes to waste. “It sometimes feels like there’s not a lot of individual things you can do to make a big difference,” she says. Corporations are the biggest polluters, but blame is often deflected onto consumers. Still, “putting food waste into composting is actually a way for individuals to make a large difference.”

If all goes well, the project will contribute to a much bigger goal of combating climate change. “Our goal is to be sustainable in the way we address things, to be a leader, to find a way to manage things better as a responsible participant on earth,” Higgins says. “We’re all in this together and we need to do the best we can.”

Have questions about composting? Ask CANU on Instagram.

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.