COVID-19 isn’t a ghost just yet. But it may be getting there.

The specter of the coronavirus loomed large at this time last year. Cases were beginning to rise heading into the winter, and a massive surge was still ahead. With no vaccines yet available to provide immunity to the virus, Halloween was a subdued affair, making COVID-19 the only ghoul in town.

But this year, Halloween is largely back, and the pandemic’s presence is becoming less spooky.

Alessandro Vespignani, Sternberg Family Distinguished University Professor of physics, computer science, and health sciences, and director of the Network Science Institute at Northeastern. Photo by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

COVID-19 cases have been declining over the past month in the U.S. Since peaking on September 1, cases have plunged around 57 percent. And over the next six months, the outlook continues to be encouraging, according to projections by the Laboratory for the Modeling of Biological + Socio-technical Systems in the Network Science Institute at Northeastern.

But a COVID-19 retreat won’t be linear, says Alessandro Vesipgnani, director of the Network Science Institute and Sternberg Family Distinguished Professor at Northeastern. And the trajectory of the pandemic will depend on how the next six months play out, he says.

“General picture, I expect bumps on the road, although every time the bump should be less threatening,” Vespignani says, with cautious optimism. Vespignani’s team of infectious disease modelers has been developing a set of projections about the possible futures of the COVID-19 pandemic. The research group is part of a network of expert disease modeling teams across the country, who collaborate with U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“It will be this long tail with bumps,” he says. “But there is no expiration date on a pandemic. At this point, it is up to us whether we let those bumps be worse or less worse.”

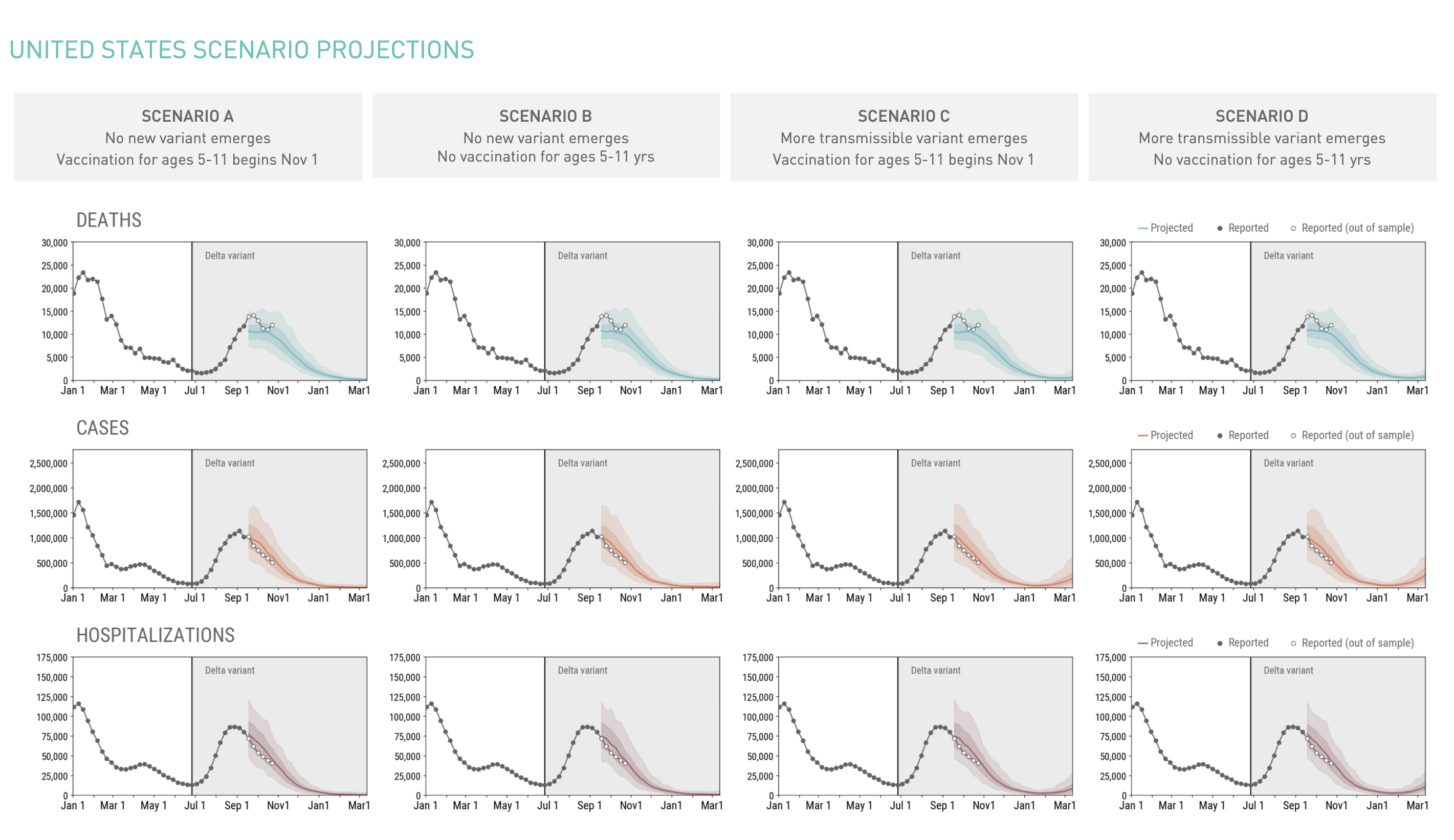

Among the many factors that could influence how the next six months of the pandemic play out, the latest projections from Vespignani’s team focused on two elements: whether vaccination for children ages 5 to 11 begins on November 1, and the possible emergence of a new, highly transmissible variant of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

Earlier this week, a U.S. Food and Drug Administration advisory panel recommended an emergency authorization of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine for children ages 5 to 11. If the FDA officially gives the vaccine the thumbs up for that age group, shots could begin being administered to those children as early as the middle of the first week of November.

That would align closely with two of the scenarios that Vespignani’s team modeled for the next six months. Both project a decline in cases, hospitalizations and deaths across the U.S. population. However, according to the team’s scenarios, if a new, highly transmissible variant emerges, it could undo some of that progress in the winter or spring.

Currently, the Delta variant has emerged as the dominant strain across the country, and no other variant has begun to challenge its reign. And with COVID-19 cases dropping, Delta seems to be in retreat, too.

“Nothing has clearly emerged that seems to be a game changer, but we need to monitor this,” Vespignani says. Every time the virus mutates, it throws projections of the future of the outbreak into question.

Another factor that could influence the trajectory of the pandemic over the next six months is how people behave this winter. In addition to the cold weather, respiratory viruses often flourish in the winter because people gather more indoors, Vespignani says. To keep COVID-19 on the decline, people may need to continue wearing masks and be cautious about large gatherings.

The current decline of COVID-19 rates is largely due to vaccinations. But Vespignani says that, more than 18 months into the pandemic, another source of immunity is becoming increasingly important, too: immunity acquired by someone who has survived a COVID-19 infection.

“It factors in at this point,” he says. “Every time you get exposed to the virus [and survive], your immune system is better armed to cope with it. And at this point we have a very large fraction of the population that has been exposed” to either the virus or to vaccines, both of which teach their immune system how to fight SARS-CoV-2.

In the U.S., more than 741,000 people have been reported to have died of COVID-19, and that is likely an underestimate, as deaths that occurred without a COVID-19 test being administered might not be reported as such.

Immunity afforded by an infection or by vaccination is “not black and white,” Vespignani says. It means that your immune system is better equipped to fight the infection and therefore you are less likely to end up in the hospital or die. He says, any amount of immunity in a community helps “make life miserable for the virus” as it tries to replicate and spread through the population.

Immunity to the virus can wane over time in vaccinated people. Booster shots could help maintain immunity levels throughout the population, Vespignani says. But, he says, efforts to vaccinate the unvaccinated communities in the U.S. and abroad will continue to be critical.

“It’s not just because we want to be generous. It’s really the selfish thing to do,” he says, explaining that the virus mutates best when it has a large pool of people to infect and spread among. Previous variants of the virus have shown they can emerge on the other side of the world and travel through our globalized society to wreak havoc at home.

For media inquiries, please contact Marirose Sartoretto at m.sartoretto@northeastern.edu or 617-373-5718.