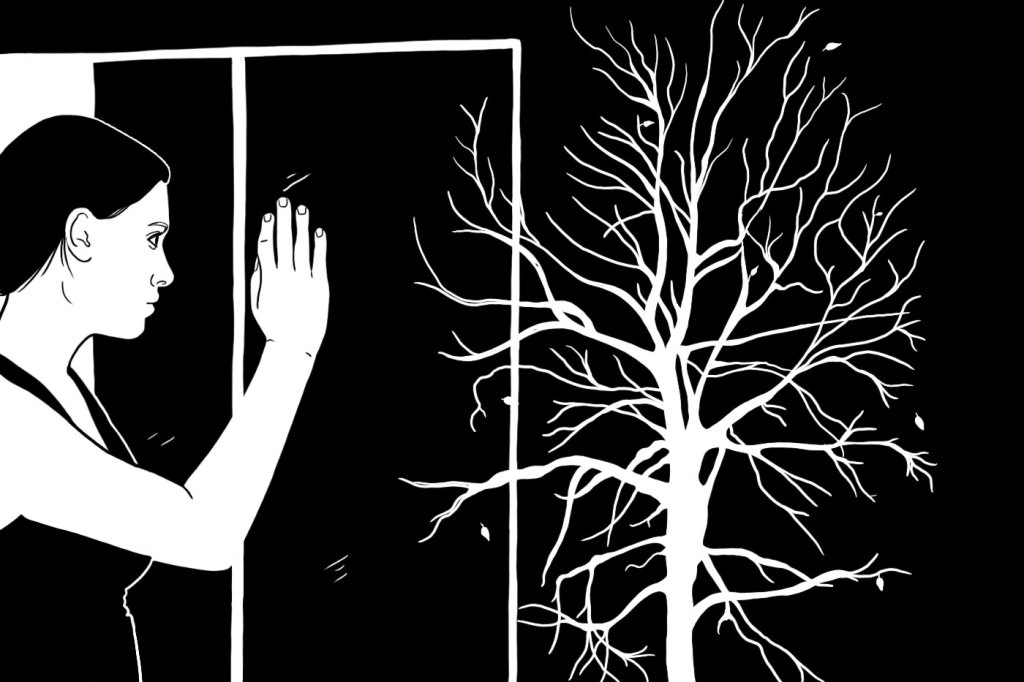

COVID-19 is more dangerous for older people. But what about locking down alone?

At the beginning of the pandemic, when the Turkish government imposed strict stay-at-home orders for all residents 65 and older, Bilge Erten’s 70-year-old father began what felt to him like an endless house arrest. Under the threat of severe financial penalties, he stayed at home for over three months until the restrictions were lifted last June.

“He complained a lot about feeling stiff from inactivity,” says Erten, assistant professor of economics and international affairs at Northeastern. “But I think the anxiety was the worst part. No one knew how long the lockdown was going to last, and that uncertainty really added to the stress.”

Bilge Erten is an assistant professor of economics and international affairs in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities at Northeastern. Photo by Ruby Wallau/Northeastern University

Unsurprisingly, forced isolation has negative effects on people’s mental health, especially older people, many of whom already suffer from loneliness. But Erten has more than a familial anecdote to prove it. In her most recent paper, she found that during Tukey’s lockdown, symptoms of anxiety and depression increased by 10 percent for those 65 and older compared to slightly younger adults, who were exempt from lockdown.

“The symptoms we looked at include somatic symptoms, such as having more frequent headaches, poor digestion, difficulty sleeping, as well as non-somatic symptoms such as feeling unhappy, crying more often than usual, finding it difficult to enjoy daily activities, and even having suicidal thoughts,” says Erten.

To test whether the increase in self-reported mental health issues derived from age-related lockdown policies, Erten and her team surveyed 1909 individuals between the ages of 59 and 70 about their emotions and physical wellbeing.

Roughly half were between the ages of 65 and 70, and therefore subject to stay-at-home orders, while the other half, between 59 and 64, were close to the cutoff age but still allowed to leave the house. They found that the 65-and-older group fared worse.

One could argue that additional factors besides the lockdown could have also contributed to the 65-and-older population’s decline in mental health. To account for these potential stressors, Erten considered whether the inability to work and subsequent loss of income was a major problem, and whether intrafamilial conflicts were exacerbated by constant interactions at home.

Neither scenario proved to be particularly prevalent among the 65-and-older population, most of whom are already retired and generally less susceptible to domestic violence than younger populations, Erten says.

Considering these factors, Erten argues that the mental health decline among the 65-and-older during the lockdown in Turkey was, more than anything else,a result of the policies enforced by the government and subsequent social isolation.

“In economics, there’s a saying: There’s no free lunch,” Erten says. “Here, I say: There’s no such thing as free policy. There’s no policy that’s not going to have side effects, and we need to be careful about what those unintended consequences are.”

Additionally, Erten says her paper is one of, if not the first, studies to show the causal relationship between social isolation and a decline in mental health. “Most of the studies before this just document how mental health distress changes over time,” she says.

Erten acknowledges that isolation is an important tactic for thwarting infectious disease. But her paper calls into question whether reducing the possibility of contracting COVID-19 by isolating outweighs the toll loneliness takes on people’s psyches.

“In the future, if there’s another pandemic, we need to consider the costs and benefits,” she says. “If the costs are as great as we demonstrate in this paper, then maybe not. Plus, we don’t know the long term effects that this will have on people’s mental health yet.”

Erten plans to conduct a follow-up study that tracks whether older people suffer prolonged mental health consequences from the COVID-19 lockdown.

“Feelings of loneliness can actually increase cognitive decay. Our long-term goal is to look at the effects of stay-at-home orders over a period of two to three years,” she says. “The mental health outcomes aren’t being taken seriously right now, and we need more research to evaluate long-term costs and benefits for better policy design in the future pandemics.”

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.