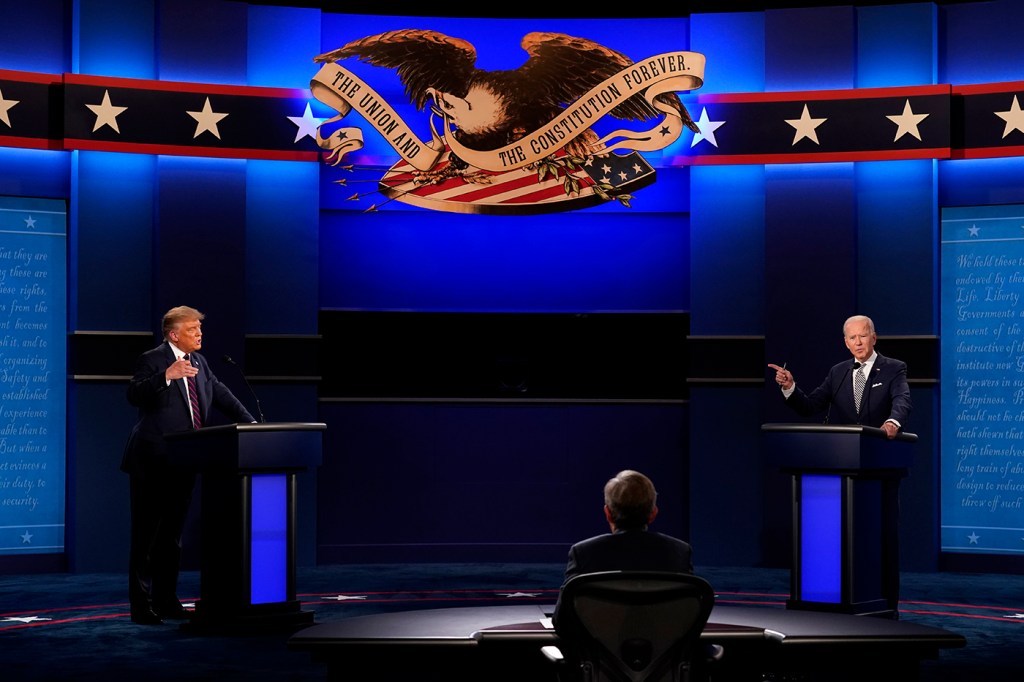

Did anyone really win the first presidential debate?

The first presidential debate between Republican incumbent Donald Trump and Democratic challenger Joe Biden was marked more by what it wasn’t—a coherent advocacy of policy differences—than what it was. Tuesday’s showdown was nearly 90 minutes of cross-talk, interruptions, and shouting that “both men probably lost,” said Nicholas Beauchamp, assistant professor of political science at Northeastern University.

So while it frustrated many viewers, the debate likely won’t affect the candidates’ standings among the voting public, said Beauchamp, who studies political behavior, campaigns, and psychology.

“If one candidate is ahead [going into the debate], and one is behind, and it’s just incoherent shouting for an hour and a half, it doesn’t help the person who’s behind,” he said.

Several polls showed Biden ahead of Trump before the debate.

Nick Beauchamp is assistant professor of political science in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities at Northeastern. Photo Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

“In this case, whichever side was in the lead going in is still winning—inasmuch as they didn’t squander their lead,” Beauchamp said.

The candidates were so mired in interruptions and off-topic comments (journalist and CNN anchor Jake Tapper described the debate as “a hot mess inside of a dumpster fire inside of a train wreck”) that it was nearly impossible to distinguish what their policy positions were, Beauchamp said.

“One of the challenges with this debate is that with so much shouting, it seems silly to try to parse any of their policies, because I’m not even sure that sort of minutiae would have even come through to people watching,” he said.

Still, Beauchamp credited moderator Chris Wallace, a journalist and Fox News anchor, for asking Trump and Biden tough questions, then pressing them when they didn’t sufficiently answer.

Wallace struggled to maintain control of the debate, but “was asking a fairly large number of hard-hitting questions,” Beauchamp said. “If this had been a normal debate, I think we would have seen Trump and Biden struggle to answer.”

Wallace asked Trump to denounce white supremacy, and pressed him for a direct statement when he evaded. He asked Biden about his record on policing and race. And the Democrat found himself “trying to thread the needle,” Beauchamp said, when Wallace asked Biden whether people should trust scientists for information about COVID-19.

“Unfortunately, it’s just hard to believe that these small details could cut through the hailstorm of this debate,” Beauchamp said.

Clear strategies did emerge from both camps, however, Beauchamp said.

“What we certainly saw from Trump was a strategy for how to exert dominance,” he said, adding that the candidate was likely trying to appeal to his base by “interrupting and harassing” Biden.

Trump also attempted to drive a wedge between far-left voters and Biden by highlighting the differences between Biden’s healthcare plan and U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders’ “Medicare for all” policy, and by hammering the fact that Biden doesn’t support the Green New Deal.

Biden’s strategy, meanwhile, “was to be the type of person you’d vote for if you were tired of Trump but appreciated his toughness,” Beauchamp said. “His aim was to seem like a reasonable, sane, firm alternative to Trump.”

Both of them probably achieved their goals, Beauchamp said, but what exactly that means for November—and beyond—is anyone’s guess.

“Even if Biden wins, normalcy isn’t just coming back,” said Beauchamp, who worked as an international election observer for the Carter Center prior to joining Northeastern. “The [alt-right group] Proud Boys aren’t just going to disappear. Issues raised by the Black Lives Matter movement [for racial justice] aren’t going to evaporate.

“One of the things I worry about is what happens in the next election, and the one after that,” he said.

For media inquiries, please contact Shannon Nargi at s.nargi@northeastern.edu or 617-373-5718.