How do today’s Black Lives Matter protests compare to the civil rights movement of the 1960s?

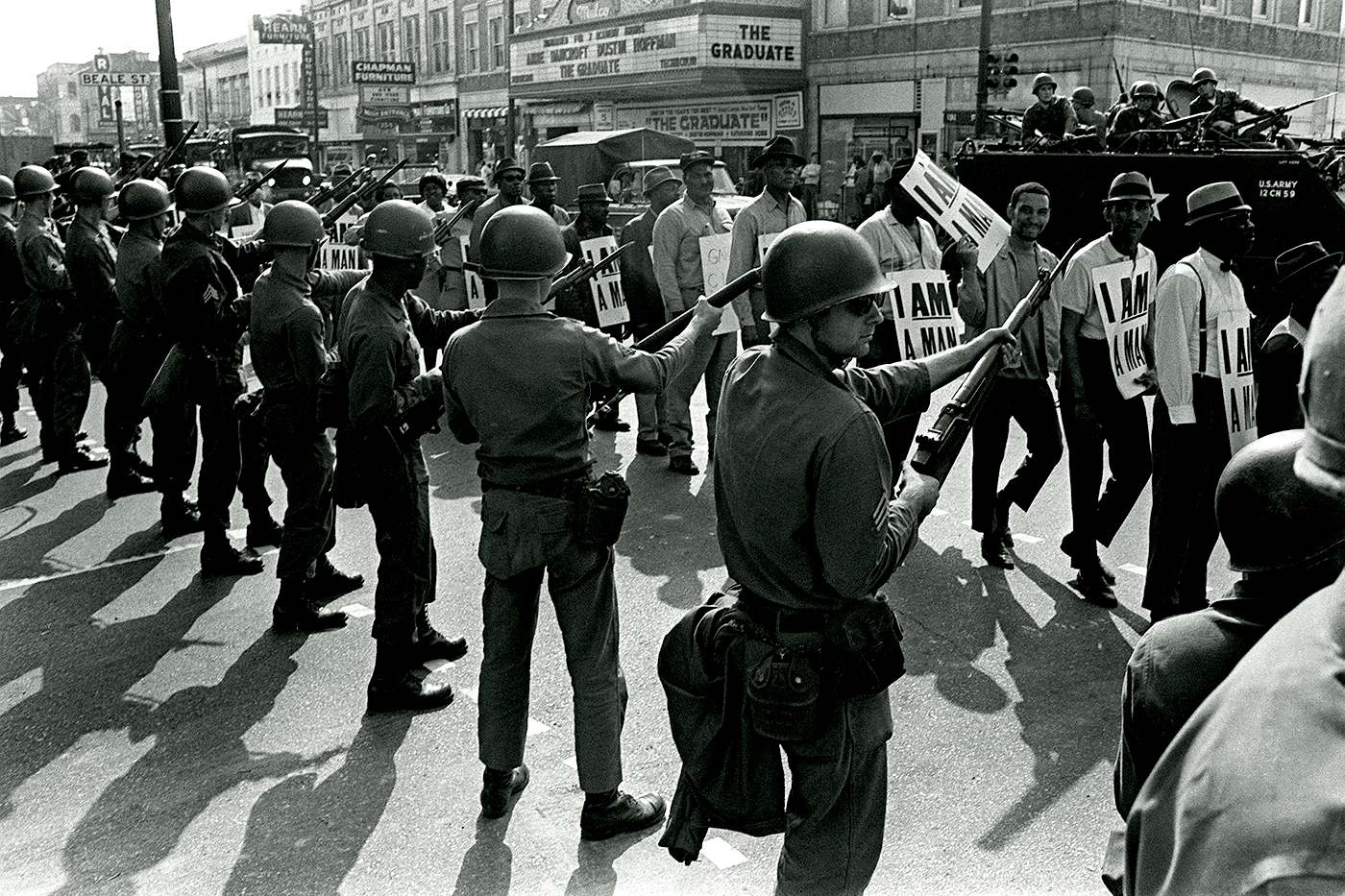

The Black Lives Matter protests that have followed the killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor by police officers remind Margaret Burnham of 1968. At that time, the national response to the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. combined with ongoing protests over civil rights and the Vietnam War to plunge an already divided nation more deeply into turmoil.

“This is taking place in a world that is not only deeply fractured, but also deeply fragile because of the coronavirus, the economic crisis that makes the country look a little bit like 1929, and the existential threat of climate change,” says Burnham, university distinguished professor of law at Northeastern. “It’s everything collapsing all around us.”

As part of Northeastern’s “Day for Reflection, Engagement, and Action” on Monday, when the university will close in remembrance of all Black people whose lives have been taken unjustly, Burnham at 2 p.m. will be leading a Facebook Live discussion, How Do We Restore Justice for George Floyd?. Her talk will be preceded by a screening of Murder in Mobile, an award-winning documentary film that tells the poignant story of a Jim Crow-era hate crime brought to light seven decades later by a Northeastern law student on behalf of the Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project, which was founded by Burnham more than a decade ago.

In 1964, Burnham was a young civil rights activist working in the Deep South, where three of her colleagues disappeared as victims of the “Mississippi Burning” murders by members of the Ku Klux Klan. As a lawyer, she represented fellow activists on behalf of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and in 2010 she headed a team that settled a federal lawsuit in which Mississippi law enforcement officials were accused of assisting Klansmen in the 1964 kidnapping, torture, and murder of two 19-year-old Black men, Henry Dee and Charles Eddie Moore.

As director of the Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project, whose staff of Northeastern students investigates acts of racial injustice that took place in the Jim Crow South from 1930 to 1970, Burnham offers a lifetime of perspective on how to confront systemic racism.

She is heartened by what she says is the unprecedented diversity of the people who are protesting the deaths of Floyd and other Black victims.

“People who are taking to the streets are doing so not just because they never thought they would see a lynching played out on on video,” she says of Floyd, who was asphyxiated when a Minneapolis police officer kneeled on his neck for nearly nine minutes. “But it’s also because they sense that there is no real plan either to face and defeat the virus, or to acknowledge and defeat the pandemic of racism in this country.

“This is what has led to the frustration, as it has in the past.”

As a young civil rights activist, you were of the same age as many students at Northeastern now. What do you take away from what must have been discouraging and frightening experiences?

What is important to remember today is that African Americans are in a class of their own in a traumatized nation. I think it would be hard to name an African American family in the United States who has not had an experience with the justice system in which they felt their loved one got the short end of the stick. We have all been personally touched by this, and for those of us who are Black, we see not just the horror of that person [George Floyd] on the ground, crying out for his mother—he literally looks like and sounds like people we know and love.

It’s deeply, deeply personal trauma. But having said that, it’s also clear that the world has been traumatized by this.

I relate back to my own experiences as a young person in the civil rights movement, when three of my colleagues—James Chaney, Michael Schwerner, and Andy Goodman—from a conference about the Mississippi Movement that we were all at—or about the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement. And we knew them. I knew them. And to this very day, I think about them, and I think about what they were thinking before they died.

That kind of trauma, it lasts a lifetime. It lasts a lifetime.

The murders of Chaney, Schwerner, and Goodman created nationwide alarm for the civil rights movement. What were the consequences legally? Do you see a connection to the recent deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor?

With respect to my friends Mickey Schwerner and Goodman and Chaney, who died on June 22, 1964, there were no consequences until recently, when that case was retried. On top of the traumatic impact of the crime itself, there is a realization that these lives don’t matter: That our justice system will move on without remedying these wrongs. And so that becomes an additional trauma.

I think what the young people who are in the streets today are saying is, it’s not the world we want to live in. We want to create our own world. We want to create a world that is responsive to our understandings of what it means to be human. And we want a justice system that’s not going to lie to us anymore, that’s not going to tell us that he died from arteriosclerosis, when actually he died from suffocation. I think that’s what it’s all about.

Why did you devote yourself to the civil rights movement?

Everybody has to understand how they come to the privileged position that they occupy. And it’s not just about white people; it’s Black people too, to know that your privilege comes at someone else’s expense. The first step is understanding where you stand in the world, and how it is that you made it. You made it to college, you’re going to get an education, you’re going to have a shot—and a lot of other people won’t. How is that? Is it just about your hard work? Or is it also about a system that’s rigged against some people and not others? It’s for all of us to understand the nature of our privilege.

And then it’s also to appreciate that this is a long road, and everyone has to figure out how they’re going to walk it. You have to figure out the battle you’re going to take. Which is the battle where you think you can be most effective? But you’ve got to pick.

You’ve got to pick a battle.

How did you decide to become a lawyer?

I was born in Birmingham, Alabama; I grew up in Brooklyn, New York. I came to law school because I was a young activist in the civil rights movement in Jackson, Mississippi. And one day I ended up in jail. A woman lawyer came and magically, I thought, got us all out of jail. It was at that point that I said to myself, this is what I want to do. I want to be able to master these tools and use them in service of the movement for Black liberation.

What was your approach to creating change in the 1960s and ‘70s?

We did exactly what young people are doing today. We pushed all the buttons—electoral politics, policy reforms.

Pressure on the streets was a critical, dynamic element to get voices heard that had been shut out of the American conversation, and so we took to the streets. We demonstrated in Washington on a very regular basis; I remember going once a year. We understood that local politics was critically important to what we were trying to do, and so a lot of us went into local government to try to make change on the local level.

I think students today have to see all of this as legitimate expressions of the imperative to change the American narrative, and to finally make a decisive pivot from the old world—the old domination of white supremacy.

In terms of the current protests, are you seeing buy-in from all sectors of society?

There have always been white allies in the struggles, including 100 years ago; these always have been multiracial movements in which people of all races participate.

What is different is the level of participation by people beyond the African American community, and even beyond the community of color. This is different from these other periods of civil unrest that have spilled over into the streets. It is very, very different this time.

How important is the next presidential election?

Well, I read President Obama’s invocation to both protest and vote, and obviously we all need to vote. But I do think that that response misunderstands the deep dissatisfaction and distrust that is reflected on the streets today. And so voting certainly is necessary, but it’s not sufficient.

People have to take these issues to the places that they work. Maybe they have to be prepared to return to the streets if it’s necessary to maintain pressure on our leadership.

I recall somebody was looking for Franklin Delano Roosevelt to move the needle on a question of policy. And FDR said, well, you know, you have to make me do it.

And that’s our job. That’s our civic responsibility to make the change happen. Voting is one way that that takes place, but the reform is going to have to be far more thoroughgoing and reach far more deeply into these systemic disaster zones if it’s going to be effective. It can’t be the same old, same old.

Is the country as divided today as it was during the 1960s, when it was torn by the battle over civil rights and the Vietnam War?

We are as divided as we were then.

I think there are large swaths of this country that have not accepted the reality that white supremacy should be seen as a thing of the past. It’s about white men who are deeply, deeply worried about their loss of authority. That’s what this is about. When I see that guy’s knee on George Floyd’s throat, that is what I see: A white man acting out of an old playbook and expressing frustration that indeed there has been change in this country.

Were you concerned that the election of Barack Obama as the first Black president would lead to backlash in the U.S.?

Yes. Yes, I was.

In 1967 the president [Lyndon B. Johnson] convened the Kerner Commission, in the wake of the riots in Newark, Detroit, and elsewhere, to look closely at some of the civil disorder, and document the disparities and the deep concerns of African Americans that led people into the streets. They issued a report that indicated the kind of thoroughgoing change that needed to take place in order to meet the unresolved grievances and dissatisfaction of these communities. And very little was done.

When President Obama came to office, one of the first things he did was to address issues of police accountability. Obviously, his reform plan was not as far-reaching or as successful in reining in police as it needed to be. But it was something.

As soon as President Trump got into office, he dismantled all of that.

It is obviously very much a backlash. We saw it after slavery with the redemption. So, this constitutes kind of a second Redemption [an 1873 demand by members of Southern states for the return of white supremacy] in which the effort is to erase any authority, any power, any equality that people of color have achieved in this country, and any progress that has been made.

If you combine the fallout of the coronavirus [which has affected communities of color disproportionately] with the deaths of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and others, you have to say that this system of white supremacy is unyielding. It’s holding on, and not by the skin of its teeth—it’s holding on fiercely and making itself truly visible. And I think that’s what people are fighting about.

Why did you launch Northeastern’s Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project?

It’s about uncovering things that people don’t want to see, that they want to avert their eyes to, so that we can fully understand how we got the criminal justice system that we have today—that if the police are involved in a killing, they can pretty much guarantee that they’re not going to be held to book. How did we get here? So our project helps tell that story.

We have those folks whose last moments, when they could not breathe, were not captured on a video. They have been lost to history. And we revive them.

This represents a huge stain on our legal system. If we were in Germany, we would call this a de-Nazification project.

The students recently uncovered a set of police files in Birmingham, Alabama, that tell the story of 140 victims of police killings in the city in the mid-20th century. Of those 140 police killings, something like 135 are African American men.

Unless you understand that the function of the police was literally to keep Negros in line, then you can’t understand anything about policing today, anywhere in this country. And so that’s what we’re trying to do.

Do you see the Justice Project making a difference?

All across the country we’ve been getting current police departments to own their histories, to understand their histories, and to insist that these histories be made available to the officers who are walking the streets today. Because you need to understand what African Americans bring to current encounters with police officers. They bring all of the trauma—all of the hostility, all of the anger, all of the rage, and they try to keep it in check, obviously. But it’s somewhere in the back of their head when they get stopped by a police officer.

That clearly makes it tough for the cops. And so officers need to learn how to deal with that.

What do you make of the destruction of property and looting that has resulted from many of the public protests?

People take advantage of chaos wherever it is. You see that when people try to rip people off and sell hand sanitizer for $50. I think there are equivalencies there.

The Trump administration has left the door open to postponing the 2020 election and has made unsubstantiated claims that voting by mail is fraudulent. Do you worry about the sanctity of the election?

I do, and I think anyone who doesn’t is not watching the press conferences. Our country is really no different from Austria in the 1930s. We think we are insulated from authoritarian rule, and we’re not.

I study the Jim Crow South, epitomizing in every way what authoritarian governments look like. It was an exclusively white regime, Blacks were excluded at every level from participation, and they died at the whim of police officers. And so it’s happened in our country before, on a racialized basis, and it could certainly happen again. I worry very much about that.

What do you make of President Trump’s declaration to use military force to quash protests within the U.S.?

I question the legality of it; I don’t think the authority is there yet. Perhaps more important than whether it can be legally justified, I certainly question the political wisdom and the morality of it.

Let me just say that this is consistent: President Trump has called on, inspired, and rewarded both police and extrajudicial violence from the very inception of his political career. You know, this is the same president who [shared a video of a supporter who said] that the only good Democrat is a dead Democrat. This is the same president who said that there are good people on both sides in response to the death of a woman in Charlottesville. This is the same president who stood silently by while somebody at one of his rallies said that the people trying to cross our border should be shot.

You reap what you sow. The president has done nothing to encourage peaceful, thoughtful resolution of these deeply ingrained divides, and as a matter of fact he has done everything to inflame them.

The police union chief of Minneapolis, by the name of [Lieutenant Bob] Kroll, attended a Trump rally [in 2019] and congratulated the president for ‘letting the cops do their jobs.’ And so the administration essentially provided a green light to the police to engage in the kind of violence that has directly led to the death of George Floyd, because apparently the police officer charged here had a record of abuse and was never disciplined for it. Any effort toward for civilian oversight was essentially removed.

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.