Billions of tons of plastic are choking the ocean. She’s here to help clean it up.

17.6 billion.

That’s how many pounds of plastic end up in the ocean on average each year, according to estimates published in 2015.

We know of this plastic, but one of the big unknowns is figuring out exactly how much of that debris is floating in the ocean, let alone how to clean it up.

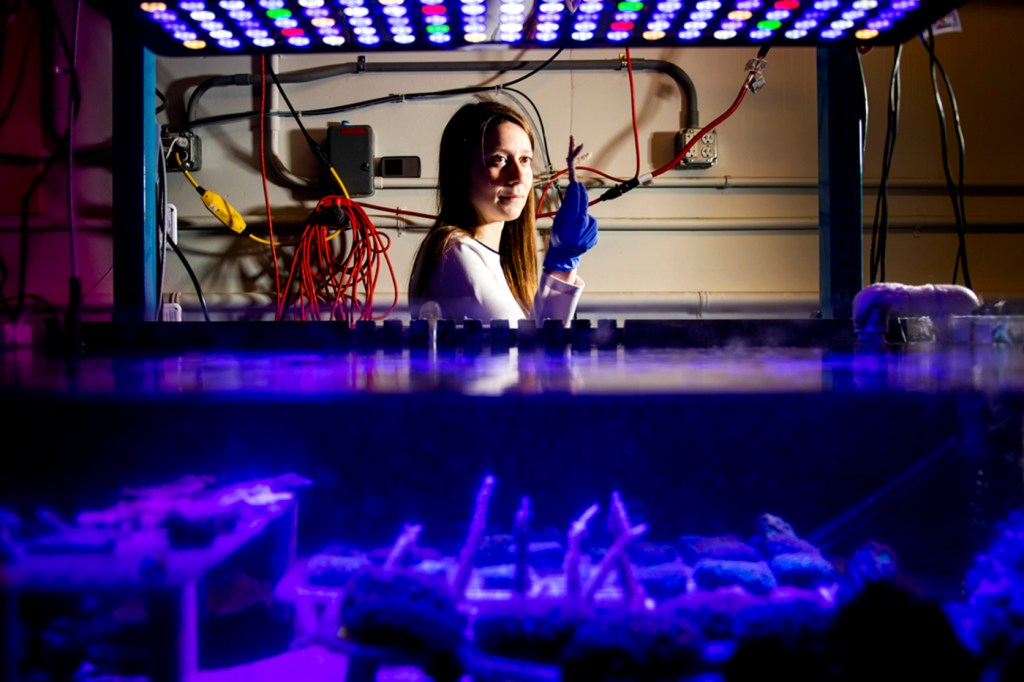

Amanda Dwyer, a graduate of Northeastern’s doctoral program in marine and environmental sciences, is on a quest to address that challenge.

“The best way to prevent this problem from becoming bigger is to decrease the amount of debris that can end up in the ocean,” Dwyer says. “Despite our best interests of trying to reuse and recycle, reducing is the first part of that mantra.”

Dwyer is moving to the Washington, D.C. area to work behind the scenes of research. Her expertise will add to the federal government’s leading office for addressing marine debris at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

At Northeastern, Dwyer has also tried to inspire the next generation of scientists through the Beach Sisters program, which helps young girls learn about marine science and involves collaborating with other nonprofit and governmental organizations to lead community service projects and afterschool programs. Working with Massachusetts State Rep. Lori Ehrlich and other state officials, they helped create an initiative to ban plastic bags.

“It was really the work of these peer leaders, these high school girls from Lynn [Massachusetts],” Dwyer says. “But that side of policy things really got me wanting to learn more about how that works at a national level.”

Dwyer wants to use what she learned from that experience to reach out to people outside her field. That, she says, might be one of the toughest challenges at the intersection of science and policy, especially for scientists who occupy a highly specialized niche.

“It can be hard to get someone to your level of passion,” Dwyer says. “It’s about making sure that you’re communicating [research] to someone who hasn’t been spending every day thinking about these problems and to someone who is actually going to be enforcing the policy but who also has so many other different issues to be concerned about.”

Dwyer’s doctoral research focused on the stresses that changing water temperatures put on coral reefs. But after a competitive selection process for one of the John A. Knauss Marine Policy Fellowships, which required interviewing with several offices at NOAA, Dwyer is taking on the global challenge of plastic in the ocean.

Fish, sea turtles, and other animals can mistake plastic for nutrients and stop eating real food altogether. And dead whales and seabirds with stomachs full of plastic keep washing up on shores around the world.

Although these marine animals are the most visibly affected, the effects of plastic reach many organisms at various depths. Studies have also shown that tiny and degraded pieces of plastic, known as microplastics, develop a thin biofilm in the ocean that coral prefer to feed on, Dwyer says. These microplastics are being found everywhere—even cycling back within the seafood on our tables.

Dwyer says there are serious long-term implications on marine and human life that need to be addressed now. That is why channeling her expertise to join other young marine scientists and help the federal government shape national policy felt like the right choice.

“It’s important to recognize how important it is that we act quickly to try to protect coral reefs, as well as other endangered species and areas in our ocean,” Dwyer says.

For the past six years, Dwyer delved into the waters of Bocas del Toro, Panama, where she studied the relationship between coral and zooplankton, the tiny floating animals and larvae that feed on other types of plant plankton.

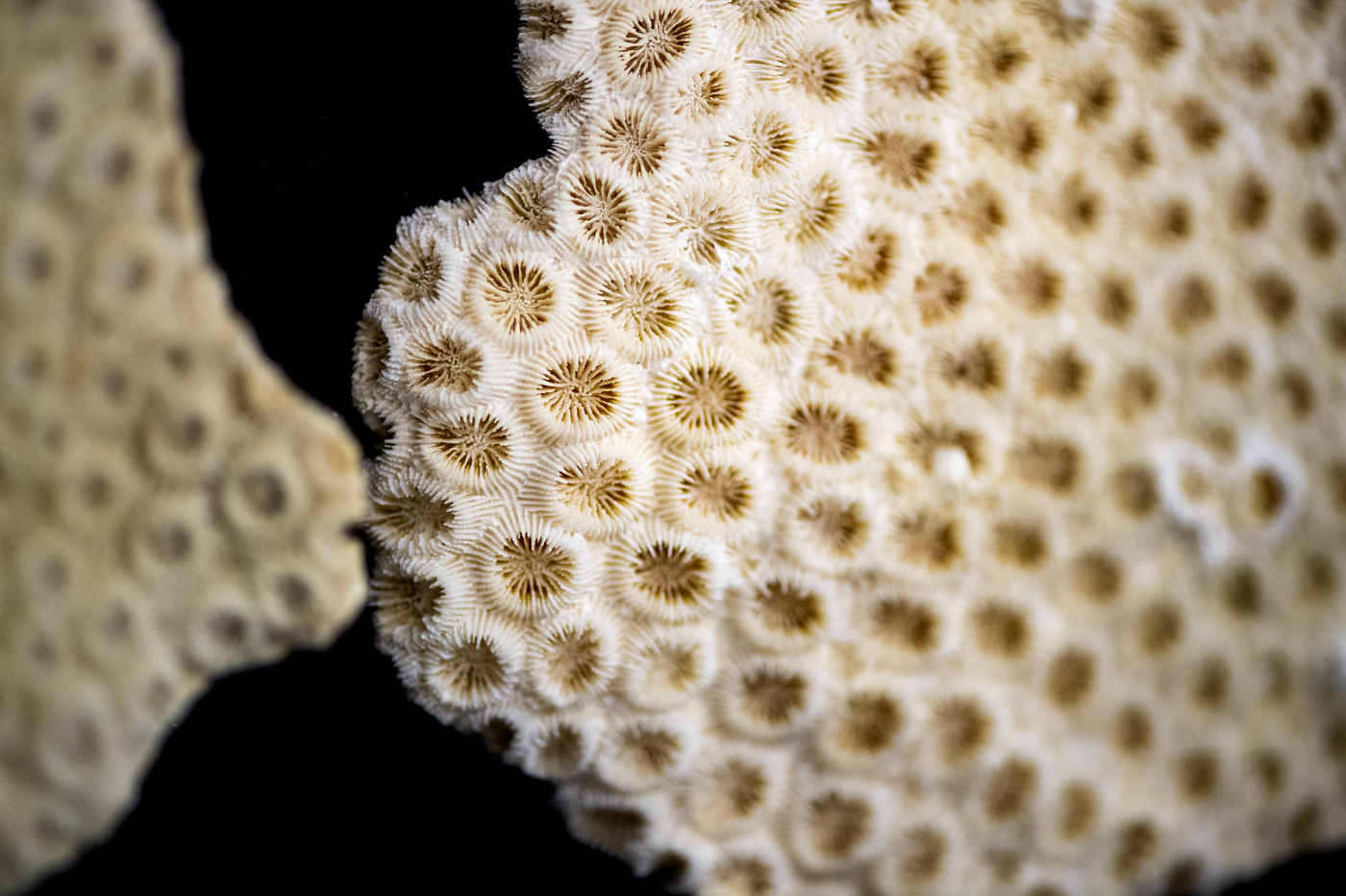

The striking color of many stony corals comes from microscopic algae called zooxanthellae, which live within coral tissue and help process nutrients. But if the ocean’s waters become too warm, that symbiosis breaks down, causing the coral to lose its coloration and revealing a pale and chalk-like skeleton. This bleaching puts corals at risk of death.

To make up for the lost nutrients, corals can change their feeding behaviors and eat more zooplankton. Yet, because the availability of zooplankton can vary with changing ocean conditions, their interaction with coral is difficult to assess.

To address those questions, Dwyer tested samples of coral tissue under different lab conditions, changing the amount of zooplankton available to the corals.

“I found that the different availabilities didn’t have any effect on the coral host physiology itself,” Dwyer says. “That was surprising to me, but good—it’s good to know that those corals can recover even in the ambient condition.”

Dwyer’s fascination with corals dates back to first grade, when, as a six-year-old in Nebraska, she and her classmates turned an entire classroom into a coral reef model with paper, clay, and other materials.

That’s how, nearly as far from the coastline as someone in the U.S. can be, Dwyer got hooked on the mysteries surrounding marine ecosystems and “learning that coral reefs were threatened when I was six years old, and continuing to learn that they’re still being threatened now.”

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.