Northeastern University looks back at the moon landing 50 years later: After the moon

Saturday, July 20, marks the 50th anniversary of the first landing on the moon. Every day this week, News@Northeastern will look at the technological breakthroughs, the political decisions, and the feats of daring that made the landing possible; the lunar landing itself; and what the future might hold for space exploration. Northeastern’s Archives and Special Collections is the exclusive home of The Boston Globe’s Library Collection, and we’ll use those images to highlight the space program and the university’s role in space exploration.

When the astronauts of Apollo 11 stepped out of the lunar module onto the surface of the moon, they opened up a whole new realm of scientific exploration.

Between 1969 and 1972, astronauts landed on the moon in a total of six NASA missions. They set up seismometers to measure shockwaves caused by meteoroids crashing into the moon or moonquakes rattling its surface, they ran experiments to measure solar wind, and collected rock and dirt samples to be studied back on Earth. Later missions brought lunar rovers (essentially space go-karts) to let astronauts explore for miles around their landing site.

Astronaut Eugene A. Cernan drives the Lunar Rover Vehicle during the Apollo 17 mission in December 1972. Image courtesy of NASA.

The last three Apollo missions were canceled because of budgetary concerns and waning public interest. But many of their parts were repurposed for Skylab, the first U.S. space station.

Crowds at Cape Kennedy watch the liftoff of a giant Saturn V rocket carrying Skylab I, the United States’ first orbiting space station on May 14, 1973. UPI/Courtesy of the Boston Globe Library Collection at the Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections.

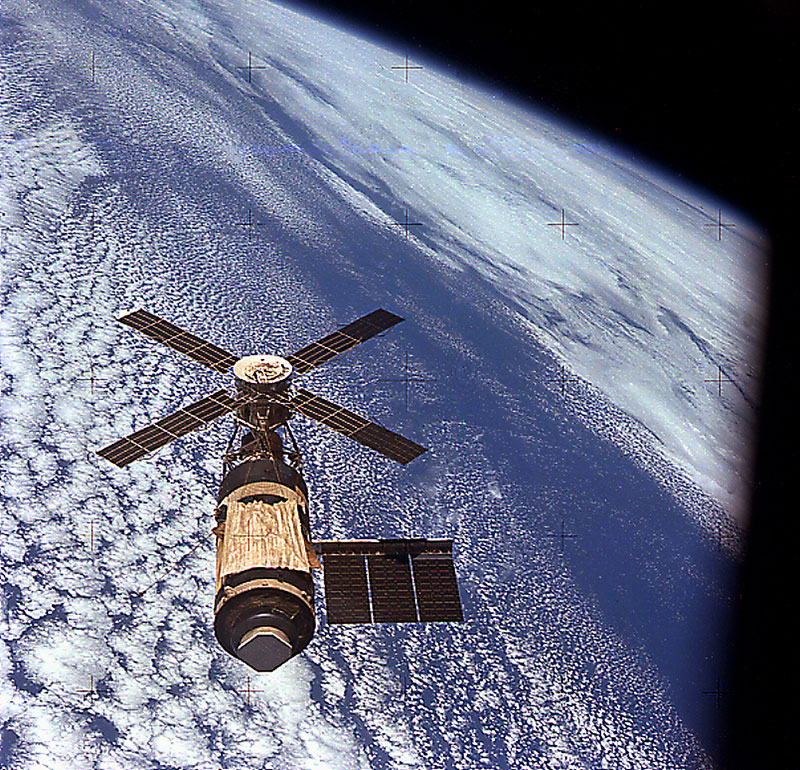

Skylab in orbit in February 1974. Image courtesy of NASA.

Three separate crews, each with three astronauts, spent time on Skylab conducting experiments in the station’s astronomical observatory and scientific laboratories. The final crew left the station in February of 1974, after spending 84 days in space.

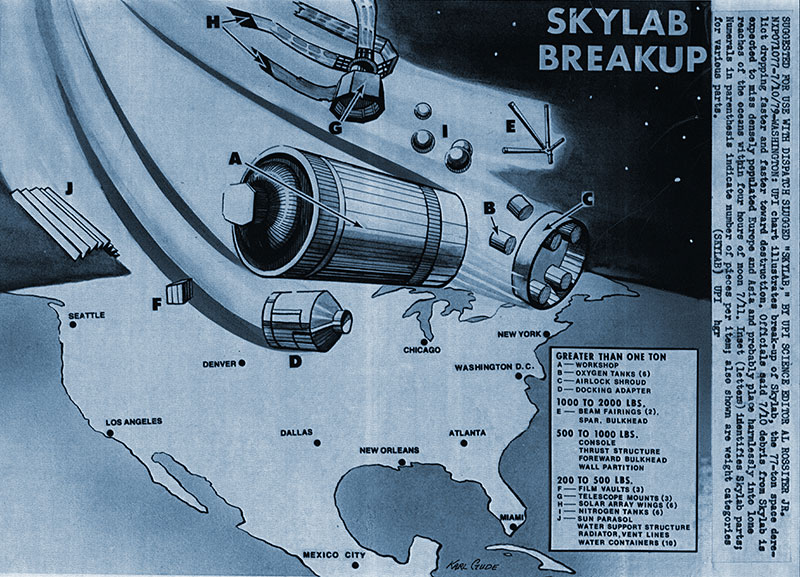

Expected trajectory of the breakup of Skylab in 1979. UPI/Courtesy of the Boston Globe Library Collection at the Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections.

American astronauts and Russian cosmonauts gather in the Soviet Soyuz spacecraft during the joint Apollo-Soyuz mission. UPI/Courtesy of the Boston Globe Library Collection at the Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections.

The Apollo program took one last historic flight in 1975. As a symbol of the improving relations between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, an Apollo spacecraft was sent into orbit to meet with a Soviet Soyuz capsule. The two vehicles docked together, and the five men (two Soviets and three Americans) spent a day and a half conducting experiments together as they orbited Earth.

NASA officials welcome the first six women astronauts, who will spend two years training for missions aboard the space shuttle, in January 1978. Left to right: Rhea Seddon, Anna Fischer, Judith Resnik, Shannon Lucid, Sally Ride, and Kathryn Sullivan. UPI/Courtesy of the Boston Globe Library Collection at the Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections.

The new era in space flight began on April 12, 1981. That is when the first space shuttle mission (STS-1) was launched. This photograph depicts the launch of the space shuttle orbiter Columbia manned by astronauts John Young and Robert Crippen. Image courtesy of NASA.

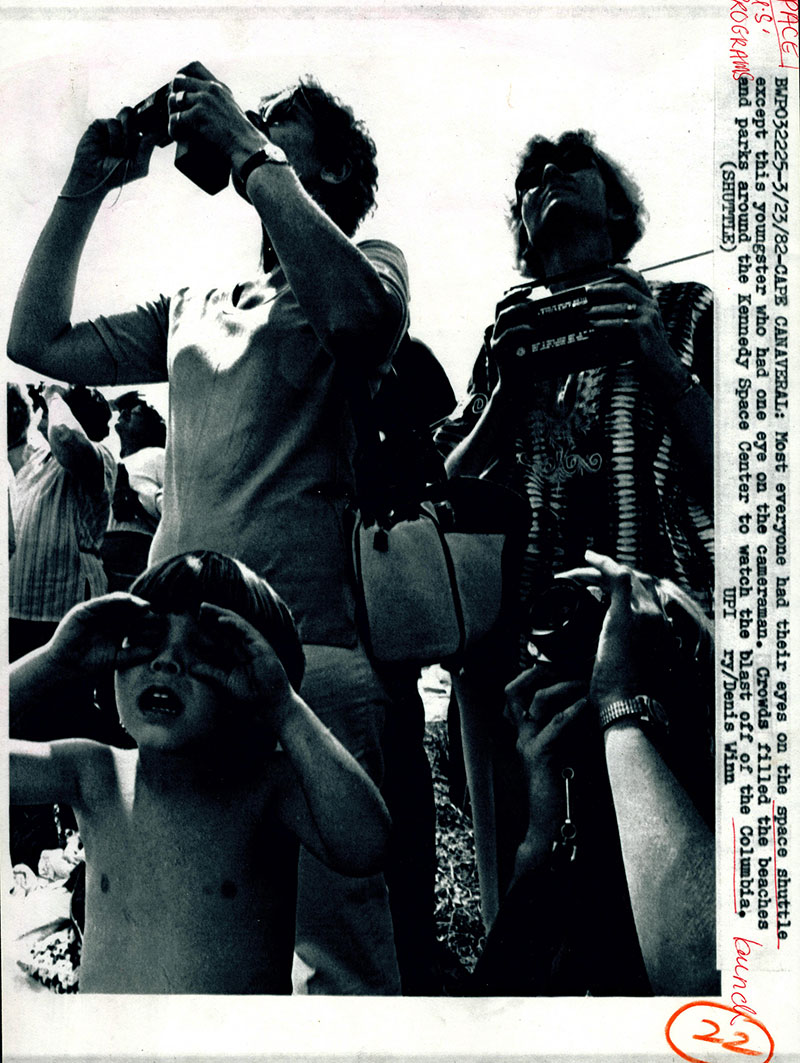

Crowds fill the beaches and parks surrounding Kennedy Space Center to watch the blast-off of the space shuttle Columbia in March 1982. UPI/Dennis Winn/Courtesy of the Boston Globe Library Collection at the Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections.

In 1981, NASA launched the world’s first reusable spacecraft designed to carry humans into orbit. Columbia was the first of five orbiters, which became known as space shuttles, each of which could carry up to 11 astronauts. Over the 30 years of the shuttle program, astronauts deployed and serviced satellites, constructed and visited space stations, and launched the Hubble telescope.

Cheering NASA employees watch the space shuttle Columbia touch down at Edwards Air Force Base in California on April 14, 1981. UPI/Les Sintay/Courtesy of the Boston Globe Library Collection at the Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections.

Astronaut and Northeastern alumnus Albert Sacco, who graduated in 1973 with a degree in chemical engineering, in front of the overhead flight deck windows on the space shuttle Columbia in November 1993. Image courtesy of NASA.

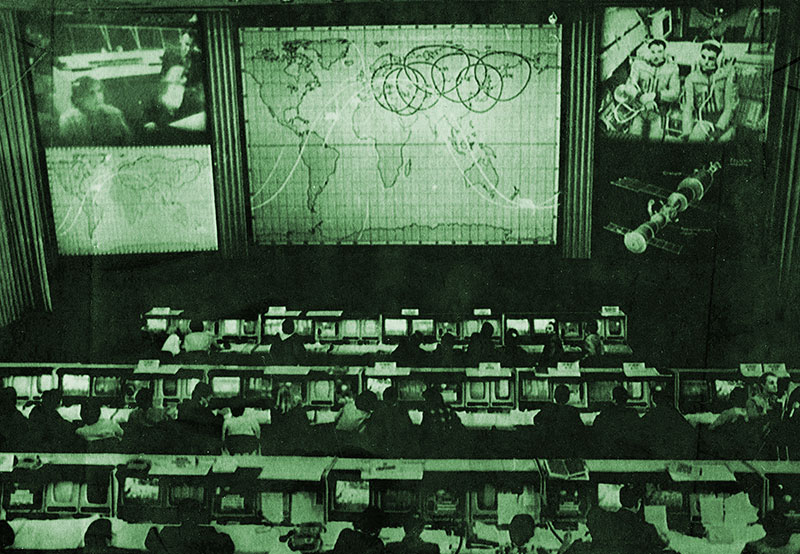

Technicians monitor the activities of cosmonauts Leonid Kizim and Vladimir Solovyov, shown on screen at top right, aboard the Soviet space station MIR from Spaceflight Control Center in Moscow on April 7, 1986. AP/Courtesy of the Boston Globe Library Collection at the Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections.

The Russian Soyuz spacecraft departs from the International Space Station in March 2014. Image courtesy of NASA.

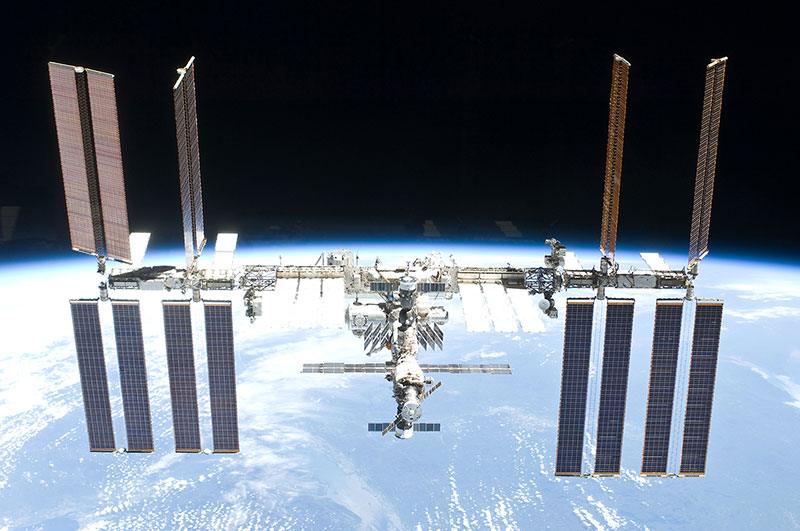

The shuttle Endeavor carried up the first U.S.-built piece of the International Space Station. The space station, which is still in orbit today, was a massive collaborative effort between the U.S., Russia, several European nations, Japan, and Canada. It is believed to be the most expensive object ever built. The experiments conducted on board and the lessons learned throughout its operation will prepare humans for missions to Mars and beyond.

View of the International Space Station taken from the space shuttle Atlantis after separation in May 2010. Image courtesy of NASA.

The benefits of space research for people on Earth are huge. Each step of the way, [space exploration] has been characterized by this wild imagination, this dreamy, outside-the-box thinking, and there’s a sense that this is part of what it is to be human—pushing the limits of what you can do.

–Mai’a Cross

Associate Professor of Political Science & International Affairs

Northeastern University