Northeastern divers combed Cozumel’s coral reef for exotic species. Here’s what they found, and why it matters

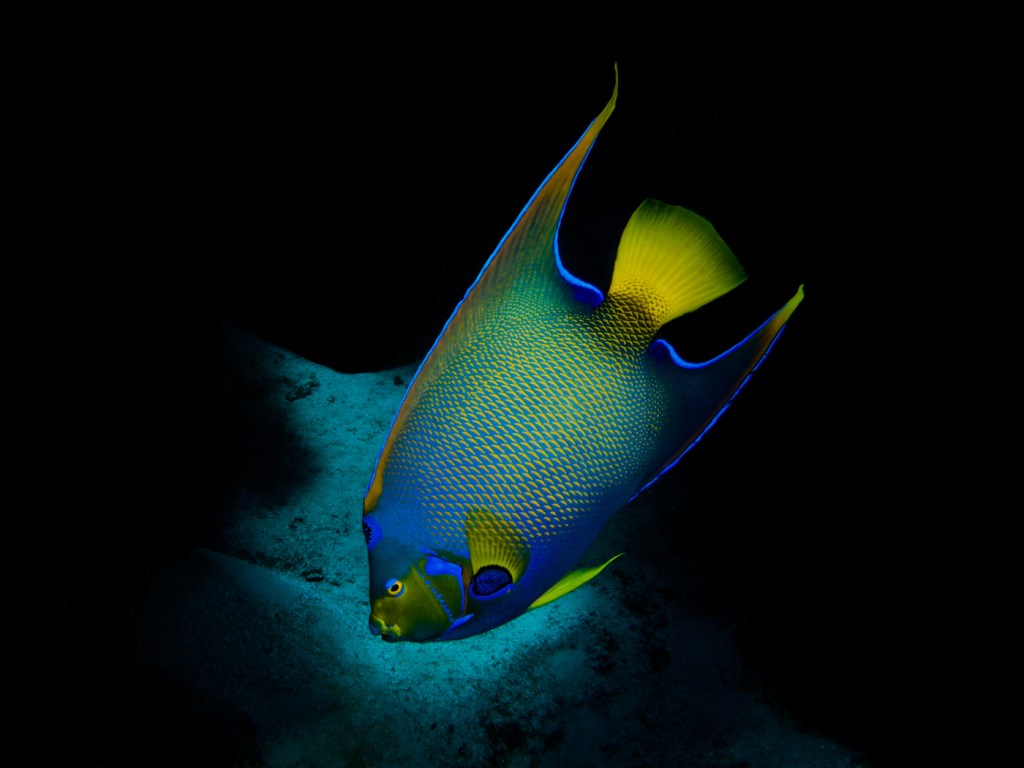

A massive Nassau grouper, four species of black corals, and a spotted drum fish were among the aquatic treasures Northeastern divers found on their expedition to Cozumel, Mexico. The drum fish was an especially lucky discovery—they are nocturnal feeders that rarely leave the protection of shelter during the day.

As researchers fan out from Northeastern’s Marine Science Center in Nahant, Massachusettes, they are spreading the word and scouting new locations to collect samples for Ocean Genome Legacy. This repository of more than 25,000 marine DNA samples was built to preserve species that may one day go extinct.

Dan Distel, research professor at the Marine Science Center and executive director of Ocean Genome Legacy, led the four-day trip to Cozumel’s coral reef. His mission was threefold: find out what sort of diversity exists in the surrounding ocean, meet with locals who could assist with research, and determine what permits are needed to collect samples in the Mexican-regulated waters. All of this lays the groundwork for Northeastern students and researchers to plan future expeditions to Cozumel.

Cozumel is a popular destination for tourist scuba divers, said Liz Magee, a program manager for the Three Seas Program and diving safety officer at the Marine Science Center. But even with dozens of boats in the marina and up to 100 eager divers in the water at once, the reef appeared to be incredibly healthy and rich.

“We did species identification surveys for fish, coral, macro algae, sponges, and invertebrates,” Magee said. “The number of species we found was really surprising.”

In one dive along part of the reef called the San Francisco Wall, the crew was treated to sightings of moray eels, king crabs, and a red spotted hogfish. The currents were quite strong, Distel said, which meant they could only engage in drift diving—a type of scuba diving where divers are carried along by the current, rather than being able to anchor at a specific point.

Back on land, the team met with local leaders to learn more about Mexico’s protected marine areas. Distel gave a presentation about Ocean Genome Legacy to a group of diving, animal care, and marine health experts, who, he said, expressed interest in supporting. Obtaining collection permits can be challenging, Distel said, because every country has different regulations. Getting help from the locals in navigating the system will be welcome, he said.

Magee and Distel were also joined by undergraduate marine biology major Jaxon Derow, who shot the underwater photos, and Ocean Genome Legacy board member Carol Horvitz, who sponsored the trip with her husband Jeffery. The crew plans to return for a pilot collection expedition in November.

Derow has been scuba diving for a decade, and taking photos of his dives for nearly as long. His ultimate goal is to become a conservation photographer.

“I want to use photography to advocate for policy change,” Derow said. “This was a really cool step in that direction.”