Tweeting under pressure

When Fan Jiyue, party secretary of Lushan County in China, visited the site of an earthquake last April that claimed the lives of nearly 200 of his constituents, it was his wrist that drew the most attention. A distinct tan line suggested he’d removed a watch before being photographed, which social media users quickly took as evidence of Fan’s corruption because the watch was believed to cost well above the customary salary range for a country official.

The next day, Fan’s name was blocked from search results on Sina Weibo, the Chinese version of Twitter, and tweets containing the name were taken down within minutes. Censorship isn’t uncommon on the microblogging platform, which counts some 500 million users. Research suggests that up to 16 percent of all “weibos”—the Chinese version of tweets—are removed, often because they contain politically sensitive issues.

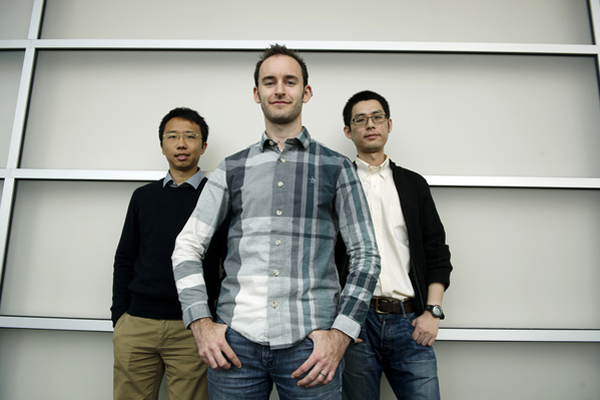

In research recently presented at the inaugural ACM Conference on Online Social Networks, Christo Wilson, an assistant professor in the College of Computer and Information Science, and his graduate students Le Chen and Chi Zhang sought to answer two important questions about censorship on Sina Weibo: first, does the phenomenon actually stifle discussions? And second, do the site’s users change their behavior in response?

The study represented the first look at the impact of censorship on users’ actual activities on the social network—and what the researchers discovered was rather surprising. “We observed no chilling effect,” Le said. “Instead, censored topics see more active users tweeting more frequently.”

The team used computational methods to analyze more than 800 million weibos. They found that more than three-dozen topics generated lots of discussion and were relevant to real-world events during the period between March 30 and May 13 of this year.

For example, the watch incident generated nearly 1,000 original tweets, 10,000 retweets, and 8,000 comments over six days. (As on Facebook, Weibo users can comment on posts.) Of all that activity, however, 82 percent was removed through various censorship mechanisms, which include thousands of crowdsourced workers who manually examine each tweet. The watch incident still went viral, even though the Northeastern research team found it to be among the top-five most-censored topics among the 37 total it examined.

Wilson and his team found that in the most censored cases, Weibo users came up with “morphs,” or alternate forms of preexisting words or phrases to prevent their discussions from being censored. For instance, instead of using Fan Jiyue’s actual name, Weibo users wrote terms such as “Lushan secretary” and “brother watch print” to evade watchful eyes.

Another case involved a fake news story about Chinese President Xi Jingpin taking a “common” taxicab. There, Wilson’s team identified a series of morphs, including words that have no relevance to the topic, but which sound or look similar when written with Chinese characters. The team found an initial spike in discussions surrounding the taxi article when it was first revealed as a hoax, but it was quickly stifled by censorship. At the same time, the morphs began to take over, generating up to four times as much activity as the initial tweets by the time the original word had fallen off the map entirely.

“Weibo is fundamentally different from other social networking sites,” said Wilson, pointing to the censorship users face.