3Qs: The move toward ‘crowdsourcing’ public safety

Earlier this year, Martin Dias, assistant professor in the D’Amore-McKim School of Business, presented research for the National Law Enforcement Telecommunications System in which he examined Nlets’ network and how its governance and technology helped enable inter-agency information sharing. This work builds on his research aimed at understanding design principles for this public safety “social networks” and other collaborative networks. We asked Dias to discuss how information sharing around public safety has evolved in recent years and the benefits and challenges of what he describes as “crowdsourcing public safety.”

How has information sharing between law enforcement agencies changed in the last century?

At the beginning the 20th century, public safety was handled by professionals at the city, state, and federal levels. Citizen engagement was moderate, though it drove priorities around resource allocation and investigations, while the use of information sharing technology was quite limited. In the 1920s and 30s as crime became more organized and crises spanned wider geographic boundaries, public safety became more professional—from the local level to the FBI—while citizen engagement became less critical and information sharing technology became more central via radios and tele-type machines.

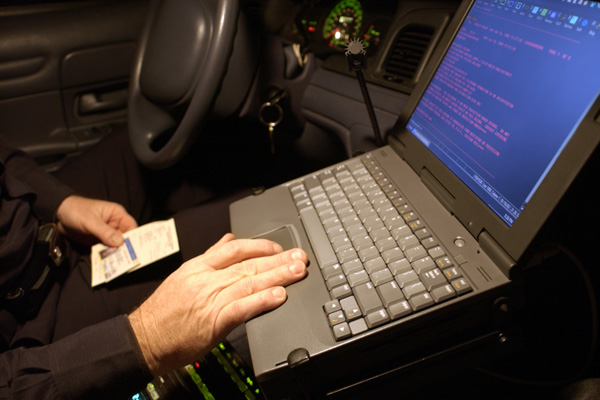

In the 1960s and 70s, the pendulum swung back to increased citizen engagement, in part due to the unrest of that time period. Public safety retained its professionalism, but community-oriented policing and the use of information sharing technology both increased dramatically, from computer-aided dispatch to inter-state information sharing infrastructure.

More recently, with the municipal adoption of information sharing and analytics tools like CopLink and CompStat—as well as corresponding state and national platforms—some agencies have reduced their community involvement efforts. To counter this trend, citizen engagement has been augmented by digital tools like web-based tip-lines and “observe and report” mobile applications.

What is “crowdsourcing public safety” and why are public safety agencies moving toward this trend?

Crowdsourcing—the term coined by our own assistant professor of journalism Jeff Howe—involves taking a task or job traditionally performed by a distinct agent, or employee, and having that activity be executed by an “undefined, generally large group of people in an open call.” Crowdsourcing public safety involves engaging and enabling private citizens to assist public safety professionals in addressing natural disasters, terror attacks, organized crime incidents, and large-scale industrial accidents.

Public safety agencies have long recognized the need for citizen involvement. Tip lines and missing persons bulletins have been used to engage citizens for years, but with advances in mobile applications and big data analytics, the ability of public safety agencies to receive, process, and make use of high volume, tips, and leads makes crowdsourcing searches and investigations more feasible. You saw this in the FBI Boston Marathon Bombing web-based Tip Line. You see it in the “See Something Say Something” initiatives throughout the country. You see it in AMBER alerts or even remote search and rescue efforts. You even see it in more routine instances like Washington State’s HERO program to reduce traffic violations.

Have these efforts been successful, and what challenges remain?

There are a number of issues to overcome with regard to crowdsourcing public safety—such as maintaining privacy rights, ensuring data quality, and improving trust between citizens and law enforcement officers. Controversies over the National Security Agency’s surveillance program and neighborhood watch programs – particularly the shooting death of teenager Trayvon Martin by neighborhood watch captain George Zimmerman, reflect some of these challenges. It is not clear yet from research the precise set of success criteria, but those efforts that appear successful at the moment have tended to be centered around a particular crisis incident—such as a specific attack or missing person. But as more crowdsourcing public safety mobile applications are developed, adoption and use is likely to increase. One trend to watch is whether national public safety programs are able to tap into the existing social networks of community-based responders like American Red Cross volunteers, Community Emergency Response Teams, and United Way mentors.

The move toward crowdsourcing public safety is part of an overall trend toward improving community resilience, which refers to a system’s ability to bounce back after a crisis or disturbance. Stephen Flynn and his colleagues at Northeastern’s George J. Kostas Research Institute for Homeland Security are playing a key role in driving a national conversation in this area. Community resilience is inherently multi-disciplinary, so you see research being done regarding transportation infrastructure, social media use after a crisis event, and designing sustainable urban environments. Northeastern is a place where use-inspired research is addressing real-world problems. It will take a village to improve community resilience capabilities, and our institution is a vital part of thought leadership for that village.