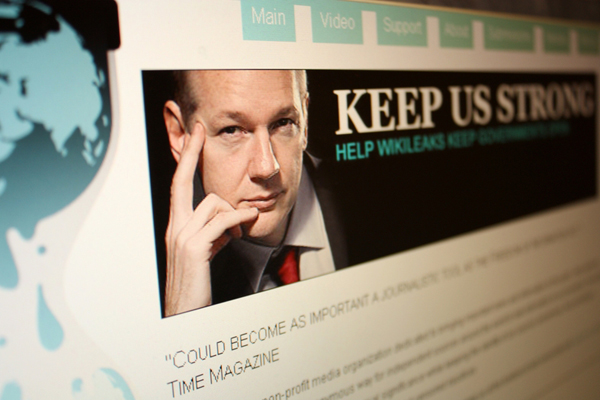

3Qs: WikiLeaks founder Assange in legal limbo

WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange has been viewed as a controversial legal figure for the past several years. He is currently seeking refuge in Ecuador’s London embassy, which is shielding him from British extradition to Sweden, where he is under investigation for sexual assault. We asked Valentine Moghadam, the director of the international affairs program in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities, to weigh in on the complicated case.

The British and Ecuadorean governments are at a standoff over the fate of Assange. Why would Ecuador be willing to go head-to-head with the United Kingdom over this issue?

It’s a matter of principle. Ecuador may be small and poor, but it has a democratic polity and is run by a progressive government. Under international law, when an individual seeks political asylum from credible fears of political persecution, asylum must be granted. In addition, Assange, as the founder of WikiLeaks, has always argued for freedom of the press, open-source information and government transparency. Many governments — especially those involved in wars, invasions and occupations, corruption or human-rights violations — take rather a different view.

In my view, Ecuador has behaved in a reasoned and reasonable manner, whereas the British government appears provocative and indeed aggressive by issuing threats to storm the embassy. Similarly, there have been very threatening statements issued here in the United States. Sen. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., head of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, for example, has stated that Assange should be prosecuted under the Espionage Act. An important point, too, is that there is considerable support in both Ecuador and Britain for the work that Julian Assange began with WikiLeaks, in addition to opposition to the British government’s decision to extradite Assange to Sweden for questioning.

Both Assange and Ecuadorean officials have expressed concerns that British police would storm the embassy to arrest the WikiLeaks founder. What are the laws that govern diplomatic outposts like embassies and how do they apply to this case?

Embassies are meant to be sacrosanct — somewhat like churches, one might say — and their inviolability is an important aspect of diplomatic relations. When in late November 2011, Iranian men protesting sanctions stormed the British embassy in Tehran, this was considered a major diplomatic breach, even if the Iranian government claimed that it had not been behind the attack. Britain cannot have it both ways by criticizing Iran for the attack on its embassy in Tehran and threatening to storm the embassy of Ecuador in London.

The UK may be standing on a national law it passed following the events of 1984, when a Libyan embassy staff member fired a gun at protestors outside the embassy, killing a British policewoman, but this case is different. No one is shooting from within the Ecuadorean embassy; instead, political asylum is being granted to someone with a credible fear of political persecution. In any event, under international law, and in diplomatic practice, embassies are never to be attacked.

Assange says his arrest would lead to prosecution in the United States over the fact that WikiLeaks has published classified documents illegally obtained from the American government. Do you think this is a realistic possibility?

I believe that it is. Assange and WikiLeaks were responsible for the release in 2010 and 2011 of thousands of U.S. diplomatic cables that revealed malfeasance in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, and indeed information on actions that suggest war crimes. Other cables showed corruption on the part of various governments and their ruling families. Five major newspapers saw fit to publish the information. For some observers, the release of the cables — as well as the “Collateral Murder” footage of the apparently indiscriminate killing of Iraqi civilians by a U.S. helicopter — was a brave and necessary act, similar to Daniel Ellsberg’s release of the Pentagon Papers in 1971. For others, this was illegal and dangerous, as well as hugely embarrassing.

For this reason, the tenor of U.S. criticism of Assange has been quite harsh, and there is evidence that a secret grand jury, called by the U.S. Justice Department, has been investigating Assange. In addition, WikiLeaks has been subject to a serious financial blockade, making the continuation of its work almost impossible. It should be noted that Assange has not been charged with any crime in Sweden; instead, the Swedish authorities issued an arrest warrant for questioning in connection with two allegations of sexual misconduct. Such allegations are very serious, especially to a feminist such as myself, even though the timing of the allegations does raise questions, coming as it did after the WikiLeaks release of the U.S. diplomatic cables.

Assange certainly needs to answer to the sexual-assault allegations, but there are real risks involved, especially the risk of extradition to the U.S., where Assange could face the fate of Bradley Manning (the young American soldier who forwarded the cables to WikiLeaks) or worse. Assange has offered to travel to Sweden if there are assurances that the Swedish authorities will not extradite him to the U.S.; they have refused his request. Nor have they agreed to his request that he be questioned in London. So his fear of extradition and prosecution is entirely warranted.